Sweetgrass sits alongside a smudge pot during a smudging ceremony outside the Juniper Hotel in Banff National Park/Jennifer Bain

Seeing Alberta's National Parks Through An Indigenous Lens

By Jennifer Bain

Eagerly, albeit awkwardly, I gathered sacred smoke wafting from an abalone shell full of burning sage into my hands, rubbed my hands together as if washing them, and then gently pulled small clouds of smoke over my head, eyes, ears, nose, mouth, heart, stomach and legs.

I’d forgotten to remove my glasses and wedding ring, but remembered being told that there is no wrong way to smudge. The goal of this smudge ceremony, led by Stoney Nakoda Elder Terry Rider, was to open my heart and mind to everything I was about to experience while looking at three of Alberta’s national parks through an Indigenous lens.

As I headed back inside the Juniper Hotel to end the smudge with Saskatoon berry soup and insight into how owner Peter Poole protects this property's wildlife corridor and sacred archaeological site (a former pit house/kiguli), I was told to have a warm, productive and hopefully deeply meaningful trip. Those words resonated, and over the next five days that's exactly what happened as I explored Banff National Park, Jasper National Park and Elk Island National Park.

Established in 1855, Banff is Canada’s oldest and busiest national park and it typically draws four million visitors a year. It's also home to the busy town of Banff. But long before colonial settlers arrived, this land was the traditional territories of Indigenous Peoples, defined in Canada as First Nations, Métis and Inuit.

Indigenous voices — once shut out of the history books, national conversation and national park and tourism experience — are finally being heard. Canada recognizes Sept. 30 as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation and Orange Shirt Day. It's a day to honor the children who never returned from the 140 residential schools run by the government and churches between 1831 and 1996, as well as survivors, their families and communities.

Jordan Ede of Mahikan Trails leads a medicine walk through Cascade Ponds in Banff National Park/Jennifer Bain

To launch a medicine walk at Cascade Ponds, Jordan Ede of Mahikan Trails stopped to leave a small offering of tobacco on the land. “You’re welcome to take pictures at any time, except when I’m leaving tobacco,” he advised, explaining that tobacco is one of the four sacred plants along with sage, sweetgrass and cedar.

“Tobacco is left in exchange for taking anything. But even though we’re in a national park and we aren’t harvesting anything today, we are still taking knowledge from the land. And it’s particularly important when it comes to hunting to thank the animal for giving up its life to sustain ours, and acknowledging one day we will return to the earth and feed the descendants of that animal.”

Ede’s mother Brenda Holder launched Mahikan Trails — using the Cree word for wolf — in 1995 to help with adventure training for Canadian and British military, but now specializes in cultural interpretive walks and workshops.

Strolling through the forest on a drizzly September day, I learned how Indigenous people in this area have long used buffalo berries (apparently the leading cause of human-bear conflicts because the bears are so fixated on eating they don't hear people coming), wild strawberries, wolf willow, rose hip (the "itchy bum berry”), cedar and trembling aspen (which contains salicylic acid, the active ingredient in aspirin). Spruce trees, Ede explained, are “basically a grocery store, pharmacy and hardware store all in one.”

The forest by Cascade Ponds where Mahikan Trails does one of its medicine walks/Jennifer Bain

He ended the walk with a lengthy Stoney Nakoda legend about the half-man, half-fish “monster” that seemed to control the wind and waves of Banff’s popular Lake Minnewanka, which was known for a spell as Devil’s Lake and Cannibal Lake.

To combat monster rumours that were impacting one of his businesses — a boat tour company — Norman Luxton (a newspaper owner dubbed “Mr. Banff") disappeared for a week in 1911 and triumphantly returned with “the monster.” For five cents, he let people see it. For another 25 cents, the savvy businessman would take them on a boat cruise to the spot where he caught the monster on the large, glacial lake.

But Ede said that after Luxton’s death in 1962, his daughter found a receipt from a build-your-own monster company in Japan and people realized the talented taxidermist had assembled a creature from the back half of a yellowfin tuna, part of an elephant trunk, legs of a crane and head of a monkey plus a hairpiece of unknown origin. This fabricated monster is now on display at the Banff Trading Post, originally owned by Luxton, where it’s called “the merman” and immortalized on t-shirts.

And yet, with the merman being a clever and lucrative hoax, the legend of a lake monster persists.

Jordan Ede shows a photo of the "merman," a fabricated monster said to live in Lake Minnewanka/Jennifer Bain

“Would you believe me if I said I’ve encountered the lake monster on multiple occasions?” asked Ede, who spent years on the long, deep and deathly cold lake as a boat captain and witnessed countless storms roll in from nowhere. Legends exist for a reason, he pointed out, and there's always a nugget of truth to them no matter how far-fetched they are.

“The monster is the lake itself — the temperature of the water, the unpredictability of wind,” said Ede. “It serves as a warning, telling people to stay off the water, but if you have to travel by water, stay close to shore, pay attention to what’s going on.”

Luxton also founded what’s now called the Buffalo Nations Museum in the Town of Banff. It was here that I picked up the museum’s map of the area and read how the Stoney Nakoda Nations people called Lake Minnewanka “Minn-waki” (Lake of the Spirits) because they respected and feared it for its resident spirits.

The Buffalo Nations Museum in Banff tells important stories about the historical and modern Indigenous presence in the area/Jennifer Bain

The map offers an Indigenous view of Banff as well as Yoho National Park and Kootenay National Park just over the border in British Columbia. It points out how the Banff mountain known as Tunnel Mountain takes its name from the fact that railway surveyors once considered drilling a tunnel through it, but it is also known by Indigenous nations as Sleeping Buffalo or Buffalo Mountain because of its shape.

“(The mountain) is considered by some as the guardian of the area,” the map explained, directing people to a Change.org petition to rename the mountain as an act of reconciliation (the act of establishing and maintaining mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people by becoming aware of the past, acknowledging the harm that has been inflicted, atoning for the causes, and taking action to change behavior).

In the contemporary area of the Buffalo Nations Museum in Banff, artist Tania Big Plume shows off some of her clothing designs/Jennifer Bain

On a museum tour, artist Tania Big Plume of the Cree, Tsuu T’ina, and Cayuga of the Turtle Clan spoke proudly of how her people once “followed the food” (namely buffalo), dried meat for winter, made animal hide clothing and honed beadwork skills. Big Plume showed off a beaded mask, a nod to COVID but also a reminder of the smallpox epidemic that devastated Indigenous communities when it arrived in what is now Canada with French settlers in the 17th century. She also shared the stories behind modern outfits she has sewn, driving home the point that Indigenous culture is not frozen in the past but always evolving.

On the main drag of Banff, Jason Carter — who calls himself “a visual artist who happens to be Indigenous" — was on hand at his Carter-Ryan Gallery to speak about how he found his calling carving sculptures and making vividly colored paintings, which are showcased at both the Calgary and Edmonton international airports. His main gallery is nearby in Canmore.

Jason Carter, an Indigenous sculptor and painter, talks about his art at the Carter-Ryan Gallery in Banff/Jennifer Bain

Leaving Banff with Joe Urie, a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta and the owner of the Jasper Tour Co., my group drove north along the fabled Icefields Parkway from the hamlet of Lake Louise in Banff National Park to the Town of Jasper in Jasper National Park.

I spent several memorable hours walking on the rapidly receding Athabasca Glacier for the first time since I was a kid, led by Tim Patterson of Zucmin Guiding, who has partnered with the glacier hiking company IceWalks to offer an Indigenous perspective on the significance of the Columbia Icefield. Patterson was born Morris Coutlee of the Lower Nicola Indian Band that belongs to the Scw̓éxmx ("People of the Creeks"), a branch of the Nlaka'pamux (Thompson) Nation of the Interior Salish peoples of British Columbia.

One thing Patterson always takes pains to counter is the misconception “that Indigenous people went to a certain place and they stopped, that history stopped.”

“We’re still here, right?” he asked.

Corin Lohmann, left, of IceWalks partners with Tim Patterson, right, of Zucmin Guiding to offer an Indigenous perspective on the Athabasca Glacier/Jennifer Bain

Jasper is Canada’s second most visited national park, with about 2.5 million visitors a year. But with 11,228 square kilometres (about 4,200 square miles), it does get to boast that it's the largest national park in the Canadian Rockies. It's also part of UNESCO’s Canadian Rocky Mountain Parks World Heritage Site.

The mountain park’s recently released management plan — a document that will guide the next decade — acknowledges a dark chapter in its history that comes up during my visit.

“The park was established in 1907,” the plan reads. “Shortly thereafter, Indigenous peoples were forcibly removed and excluded from park boundaries, as colonial government policies at the time considered Indigenous peoples to be incompatible with park establishment. Other Government of Canada policies — including restrictions on hunting and gathering, restrictions on leaving reserves, prohibitions on cultural practices and ceremonies, and removal of children to residential schools — further prevented Indigenous peoples from travelling through, harvesting and exercising cultural practices in what is now the park. These government practices and policies disconnected Indigenous peoples from their traditionally used lands and waters and caused significant negative impacts to their communities that persist to this day.”

One of Parks Canada's four key strategies for Jasper is to strengthen Indigenous relations. The park is in Treaty 6 and 8 territories, as well as the traditionally used lands and waters of the Anishinabe, Dene-zaa, Nehiyawak, Secwépemc, Stoney Nakoda and Métis.

Parks Canada says it is now working with more than 20 Indigenous communities and organizations with connections to Jasper. Since the Jasper Indigenous Forum was created in 2006, access to traditional lands and activities has improved and there is designated area for traditional activities, free park entry for partner communities, and cultural use permits for harvesting of plants and medicines. Indigenous partners hope to see Indigenous knowledges and languages woven into park initiatives, be more involved in park management, and have more employment and economic opportunities.

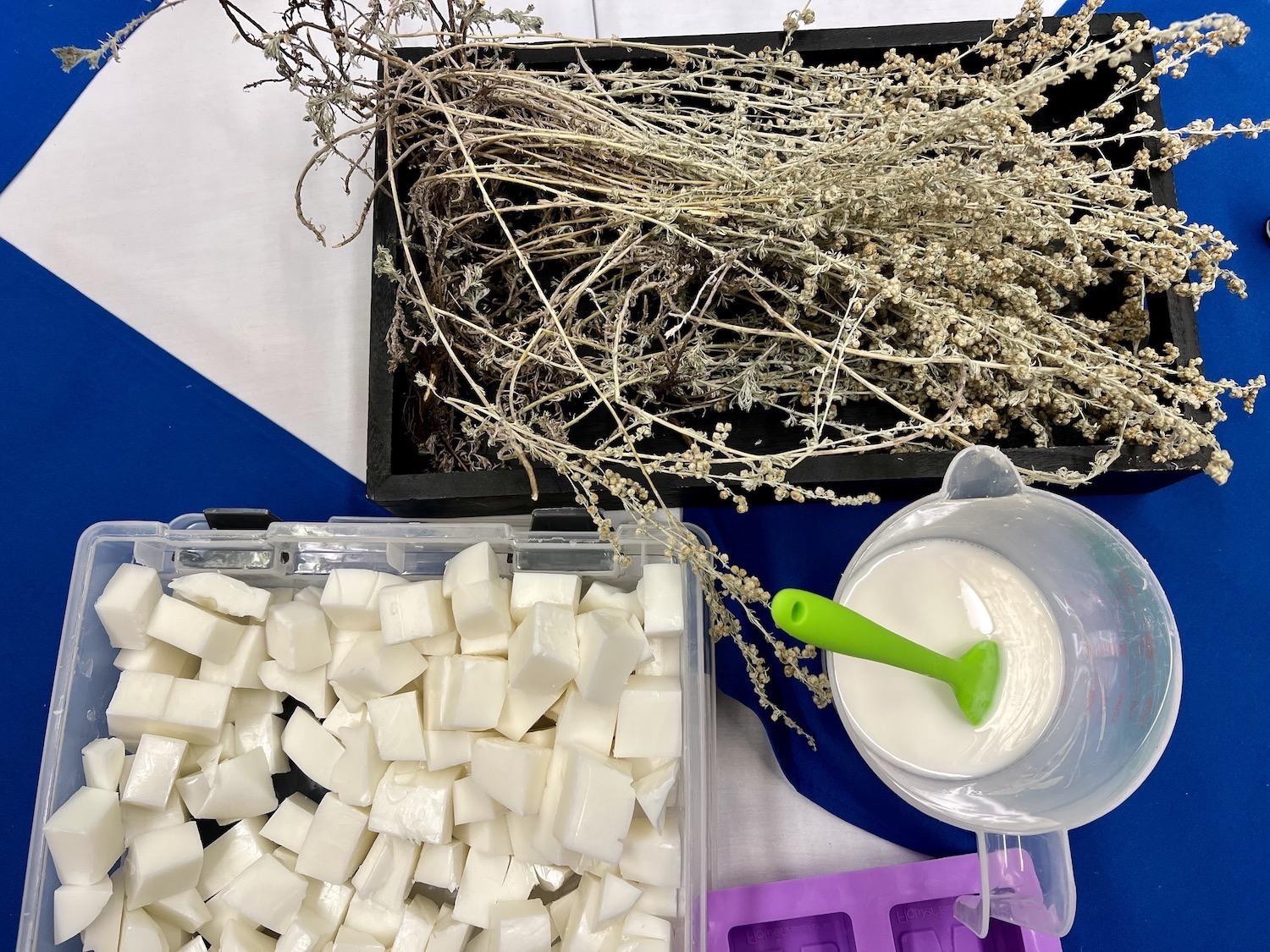

Fallen Mountain Soap is an Indigenous-owned company that makes artisan soap, like this one made with dried sage/Jennifer Bain

Lauren Moberly is the descendant of people who were forced out of Jasper. She had planned to meet our group at what was once her family’s homestead to harvest wild ingredients and show us how she makes artisan soap for her young company Fallen Mountain Soap. But the Chetamon wildfire disrupted that plan. The fire started Sept. 1 with a lightning strike and Parks Canada had to ask visitors to temporarily stay away while Jasper grappled with power outages.

The Ewan and Madeline Moberly Homestead escaped the wrath of the fire, and the Grand Cache-based Moberly drove to the Overlander Mountain Lodge just outside the park's eastern edge to share her story.

Handing out dried sage she foraged just before the fire, she taught us to make beautiful bars of soap. As we worked, Moberly recounted how her relatives homesteaded, farmed, ran fur trading posts and guided in this area before being kicked off their land and forced to start over in another part of the province. She shared vintage family photos, including one that shows her great grandfather Joe McDonald hanging out with Hollywood starlet Marilyn Monroe during the filming of 1954’s River of No Return.

Fallen Mountain Soap's Lauren Moberly shows a photo of her great-grandfather who appeared in a Marilyn Monroe film in the 1950s/Jennifer Bain

Moberly also shared recent photos of the homestead itself — a log cabin with square hewn logs fit together by using a unique form of dovetailing — and the outdated Parks Canada signage at the site that doesn't yet acknowledge the displacement. She remembered how her mother always forbade her from even picking a flower during childhood visits to the homestead, and said it's only in recent years that she has been welcome to harvest there.

“I think a lot of us just go to the homestead for the connection,” she mused.

Connection to the land is what drew chef Scott Jonathan Iserhoff to Elk Island National Park after he moved from Ontario to Alberta seven years ago. Elk Island isn't a showy mountain park and it attracts about 400,000 visitors a year. It's 3.5 hours east of Jasper and 35 minutes east of Alberta's capital city Edmonton. It protects forests, grasslands, lakes, rivers and wetlands in the Southern Boreal Plains and Plateaux Natural Region.

“When we moved to Edmonton I didn’t like it," Iserhoff remembered. "Then we drove out here and cooked over the fire and it actually reminded me of a place in Timmins. So I started coming out here every week, sometimes every day. Even though I’m far from home, I’m still on the land.”

Edmonton chef Scott Jonathan Iserhoff of Pei Pei Chei Ow cooks in a fire pit in Elk Island National Park/Jennifer Bain

Now Iserhoff is gaining national attention as the chef-owner of Pei Pei Chei Ow, a food and education company based in Amiskwacîwâskahikan Treaty 6 (Edmonton). The company name means “Robin” in the Omushkegowin (Swampy Cree) language and was given to him as a childhood nickname by his grandfather.

Iserhoff returned to the park to cook a meal of braised cow tongue on corn mush for us in the Astotin Lake Recreation Area. When his bannock burned on the wood-fired fire pit, he tore it into bite-sized pieces and transformed what should have been a loaf of quick bread into a panzanella-style bread salad with tomatoes. He finished the afternoon meal with grilled British Columbia peaches drizzled with sweetgrass syrup.

“For us, it’s just Indigenous food,” he said. “It’s not contemporary. It’s not modern. It’s just Indigenous.”

Braised cow tongue and corn mush cooked in Elk Island National Park by chef Scott Jonathan Iserhoff/Jennifer Bain

Originally established in 1906 to protect what was then considered to be one of Canada’s few remaining herds of elk, Elk Island is the only national park in Canada that is completely fenced. While there are still about 500 elk here, the big draw is bison. Between 1907 and 1912, the Canadian government purchased one of the last herds of bison from a Montana rancher and shipped 700 wild bison by train to this park.

Now Elk Island is home to a conservation herd of about 400 plains and 300 wood bison, which are kept on separate sides of a highway. Surplus bison have been sent to auction and provided to other national parks, Canadian and American conservation projects and Indigenous nations.

Joe Urie, the Métis owner of the Jasper Tour Co., shows off a caribou antler, bison skull, beaver pelts and more in Jasper National Park/Jennifer Bain

Throughout my time in Alberta, Urie — who did triple duty as tour guide, cultural host and driver — spoke often of the Buffalo Treaty, a historic 2014 cross-border pledge first signed at the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana by multiple First Nations to restore bison to millions of acres of land.

Plains bison were returned to Banff in 2018, but Urie still longs to see the animal known as bufloo in Michif, the Métis language, roam near his home in Jasper. When he finally spotted a bison bull calmly grazing by the side of the road in Elk Island, he got downright euphoric and couldn't get enough of the magnificent creature that helped feed and clothe his ancestors.

"I just get filled with joy when I see this."

A bison grazes by the road in Elk Island National Park, Canada's only fully fenced national park/Jennifer Bain

Urie stayed joyful because we moved on from Elk Island to the nearby Métis Crossing and saw plenty more "bufloo" — plains, wood and even rare white bison (that were selectively bred).

Alberta's first major Métis cultural interpretive destination spans 688 acres within the Victoria District National Historic Site, a large, rural cultural landscape characterized by farmlands organized in long, narrow river lots common among Métis farmers running back from the North Saskatchewan River. It's interesting to note that Parks Canada historical signage at the site that speaks to how this agricultural community was formed is in five languages — English, French, Ukrainian, Michif and Cree.

Métis Crossing celebrates the children of the fur trade whose French, Scottish and English fathers married First Nations women. The crossing sits on historical Métis river lots and the cultural heritage gathering center was designed by Métis architect Tiffany Shaw-Collinge. I stayed in the new 40-room boutique lodge but checked out the camping and soon-to-unveiled star-watching pods.

Some of the white bison herd at Visions, Hopes and Dreams at Métis Crossing Wildlife Park/Jennifer Bain

I tried archery, paddled a voyageur canoe along a historic fur trade route, dined on wild rice pudding and drank Saskatoon berry lemonade. But what stood out was the Visions, Hopes and Dreams at Métis Crossing Wildlife Tour, a joint venture partnership with non-Indigenous rancher neighbor Len Hrehorets that has been lauded as an important step towards reconciliation. CEO Juanita Marois drove us across 320 acres divided into five paddocks full of heritage species, like elk and the bison that have been returned to these traditional Métis lands for the first time since 1865 and that allowed our truck to drive among them as long as we blasted country music.

The bison clearly love this land, as do the people who get to experience it.

"The trees are turning, the water's flowing, you can hear the geese in the river," Hrehorets enthused. "Everybody know what heaven's like? This is as close as you're ever going to get."

Add comment