An aerial view of Fort McNab National Historic Site on McNabs Island in Nova Scotia/Parks Canada

Exploring All Five Stops Of The Halifax Defence Complex

By Jennifer Bain

The garter snake shoots me the side-eye as I arrive at Fort McNab National Historic Site and inadvertently disturb the peace. Endangered barn swallows swoop confidently about, almost as if they know they’re a species at risk and it’s illegal to disturb them or their nests. It’s also against the rules to camp which is probably news to the young couple who’ve kayaked over to McNabs Island and brazenly pitched a tent in the ruins.

A standard forest green Parks Canada sign offers a silent welcome, and remnants of an imposing black fence remain. But there are no staff, interpretative signs or visitor services at this hidden military gem that too few people ever visit.

“When you’re out there, it’s sort of a wild west,” Captain Dave Backman of North West Arm Boat Tours said as he dropped me on the island this morning. “The place sort of manages itself.” Promising to return five hours later, he predicts I will see “upwards of six people” all day as I explore this island near the entrance to Halifax Harbour in Nova Scotia.

Captain Dave Backman of North West Arm Boat Tours takes people to McNabs Island/Jennifer Bain

The captain isn’t far off, though it’s more like six groups of people — mainly couples and families — who have the gumption to get themselves here by kayak, private boat or charter to experience the quiet island's rich history and unspoiled nature.

Parks Canada has no trouble drawing visitors to the centrally located Halifax Citadel National Historic Site and the newly accessible Georges Island National Historic Site. But not many people realize that these are just two spots out of the five that make up the Halifax Defence Complex. The Prince of Wales Tower National Historic Site is in a popular local park within walking distance of downtown, York Redoubt National Historic Site is a daunting 25-minute cab ride away from downtown, and Fort McNab — well, it will eat up the better part of your day.

These five sites are “integral to the very fabric and essence of Halifax,” Parks Canada says in its 2020 management plan for the Halifax Defence Complex. “Their architecture and aesthetic contribute to the distinctive heritage character of Halifax and they serve as reminders of the city’s rich military history.”

I set aside one whirlwind weekend in June to explore all five fortifications built by British and Canadian military forces over the years to protect Halifax and its famously ice-free harbor. The enemy attack never came, but each threat brought new guns and new defences.

Parks Canada has a sign at the self-guided Fort McNab National Historic Site at the southern end of McNabs Island/Jennifer Bain

Strategically located on the southern side of McNabs Island, Fort McNab was built between 1888 and 1892 and acted as a gun battery and gatekeeper to the harbor until it was decommissioned in 1959. It was the first local fortification to use breech-loading guns and housed the port’s examination station through two world wars, ensuring visiting ships didn’t threaten port security.

“The guns, shelters and searchlight emplacements are an enduring reminder of the importance of this once-formidable fort,” Parks Canada explains on a page I’ve printed off its website, although to be honest I mostly have no idea what I’m looking at as I poke around. The grass is mowed by maintainence staff, but the vacant buildings have been left as is. One — with a treacherous, mossy stairwell to its basement — is flooded.

I’ve also printed an old pamphlet for “McNabs and Lawlor Islands Provincial Park” and learn that Halifax was once Britain’s chief naval base in North America. When British military officer Edward Cornwallis established a settlement in Halifax in 1749, he granted most of this island to his nephews. Peter McNab, who bought the island in 1782, cleared the land, established tenant farms and remained a presence for more than 150 years so that's where the name comes from.

McNabs Cemetery at Fort McNab is fenced and locked and there is even barbed wire/Jennifer Bain

The fort was built around McNabs Cemetery — the small McNab family graveyard — and was called “the world’s best guarded graveyard” in Thomas H. Raddall’s 1948 book Halifax: Warden of the North. Today, 13-odd headstones are kept off-limits behind a locked gate and imposing fence.

McNabs Island is about five-kilometres (three-miles) long and 1.5-kilometres (0.9-miles) wide, and my five hours briskly hiking it end to end it provide only a cursory look at its forest, beaches, salt marshes, sheltered coves and two forts. Fort Ives at the northern end of the island dates back to 1864 but isn’t managed by Parks Canada.

There's no trace anywhere that I can see that this land is a provincial park. Instead, it's the non-profit Friends of McNabs Island Society that has done remarkable work maintaining trails, erecting outhouse privies, creating directional signs and placing interpretive signs in a picnic shelter near the pier.

This Fort McNab building is partially flooded and explorations are at your own risk/Jennifer Bain

The society runs a comprehensive website and leads guided heritage and nature tours every summer, expanding the story well beyond the Parks Canada-managed fort to discuss the island’s importance to the Mi’kmaq, early French settlers and the British as well as to people like “midway king” Bill Lynch. The society highlights the Victorian gardens its volunteers are restoring, and relays how the SS England was quarantined off the island in 1866 because of cholera, and how the A.J. Davis Soda Pop Factory was once here when the island was a hotspot for leisure.

My trip unfortunately doesn’t coincide with the guided tours so I snag a copy of the society’s 2008 book Discover McNabs Island instead and chat with the society’s Cathy McCarthy by email. “Wear good sneakers or hiking boots, bring bug spray and sunscreen and wear a hat,” she advises. “Bring water and your lunch.”

Ambassatours has just launched a regular McNabs Island tour, trumpeting the unspoiled island’s “wild and woolly past.” But the timing doesn’t work so I book Backman for a private, custom shuttle in his Zodiac-style SeaBright boat. On the 45-minute journey back to shore, he stops below York Redoubt so I can photograph the graffiti-covered, wartime-era bunkers that stand by the ocean below the cliffside ruins.

At York Redoubt, extensive signage lets visitors know what they are seeing and why it's important/Jennifer Bain

York Redoubt was built on a steep bluff at the harbor entrance in 1793 and operated until 1956. Now hikers come for the forested trails and ocean views, while history buffs love the fortification's ruins and the muzzle-loading rifles mounted on the ramparts.

Like Fort McNab, York Redoubt is self-guided but with plenty of interpretive signs — some clearly dated but still readable — so you can figure out what was a military store, where the cookhouse was and how an engine room for searchlights worked.

It’s a delightfully foggy day, though, and I miss the path down to the water to see the graffitied bunkers. I do learn that during the Second World War, York Redoubt was “the nerve centre for harbour defences” including an anti-submarine net which stretched across the harbor’s entrance to McNabs Island.

The Prince of Wales Tower National Historic Site has a Martello tower from the 1790s/Jennifer Bain

After practically having Fort McNab and York Redoubt to myself, it’s somewhat jarring to find Point Pleasant Park teeming with runners, dog walkers, cyclists and boisterous groups out for a weekend stroll. The Prince of Wales Tower takes up just a small portion of the park and showcases North America’s first Martello Tower, inspired by small stone tower in Corsica that resisted a joint British naval and land attack for several days in 1794. Built in the 1790s, this squat, round structure with eight-foot-thick stone walls once protected British sea batteries from a French landward attack. These batteries, in turn, defended seaward approaches into the harbor and the entrance to the Northwest Arm.

While the other Halifax Defence Complex sites were used until after World War II, changing military technology made York Redoubt obsolete by the time the land surrounding it was leased to the city for a park in 1866. Today it's a popular spot for grad and wedding photos.

I’m walking through downtown Halifax when the Noon Gun roars at the Halifax Citadel, the city’s flagship tourism offering. Like everyone, I stop to photograph the iconic Old Town Clock — which has been operating since 1803 — and the 78th Highlander standing sentry at the site entrance.

The new Fortress Halifax exhibit at the Halifax Citadel National Historic Site/Parks Canada, Aaron McKenzie Fraser.

Set on a hill overlooking downtown, the Citadel was so strategically important that it was built four times — but it was never actually attacked.

There is almost too much to do at the Citadel, with historic period rooms to explore and a new exhibit Fortress Halifax: A City Shaped by Conflict that chronicles the history of what the Mi'kmaq call Kjipuktuk through its establishment as Halifax in 1749 to today. Stories of the MI’kmaq and British, French, Acadian, Black Loyalist and other immigrant settlers are told. There’s a canteen, guided tours and a chance to don a military uniform for a photo. There are costumed interpreters spread throughout the site.

Parks Canada reports that about 200,000 people pay to come inside the Citadel walls each year, while about 600,000 use the grassy hill surrounding it annually. York Redoubt gets about 25,000 summer visitors and 50,000 the rest of the year. Numbers for Prince of Wales Tower or Fort McNab aren’t available, and Georges Island launched during the pandemic so it's still too soon to get a clear picture of its visitation numbers.

Tiny Georges Island in Halifax Harbour has been opened seasonally since August 2020/Parks Canada, Mike Bayer

Halifax travel writer Helen Earley — who gamely drives me to York Redoubt and Prince of Wales Tower — devotes a chapter of 25 Family Adventures in Nova Scotia to the Citadel and another to McNabs Island (the entire island, not just Fort McNab). She sings the praises of Georges Island in a chapter on the waterfront, noting that its August 2020 reopening, and the “continuous care” for McNabs, “suggests that a new golden age of island exploration in Halifax Harbour is upon us.”

That’s exactly how it feels when I board the Kawartha Spirit with a small but exuberant crowd of tourists for the 10-minute ferry ride to Georges Island, which is so close to shore that I can clearly see it from my room at the Westin Nova Scotian.

The tiny island in the heart of the harbor has a lighthouse, fort and hidden fortifications dating back more than 200 years. Much of it is roped off so people can only visit certain areas.

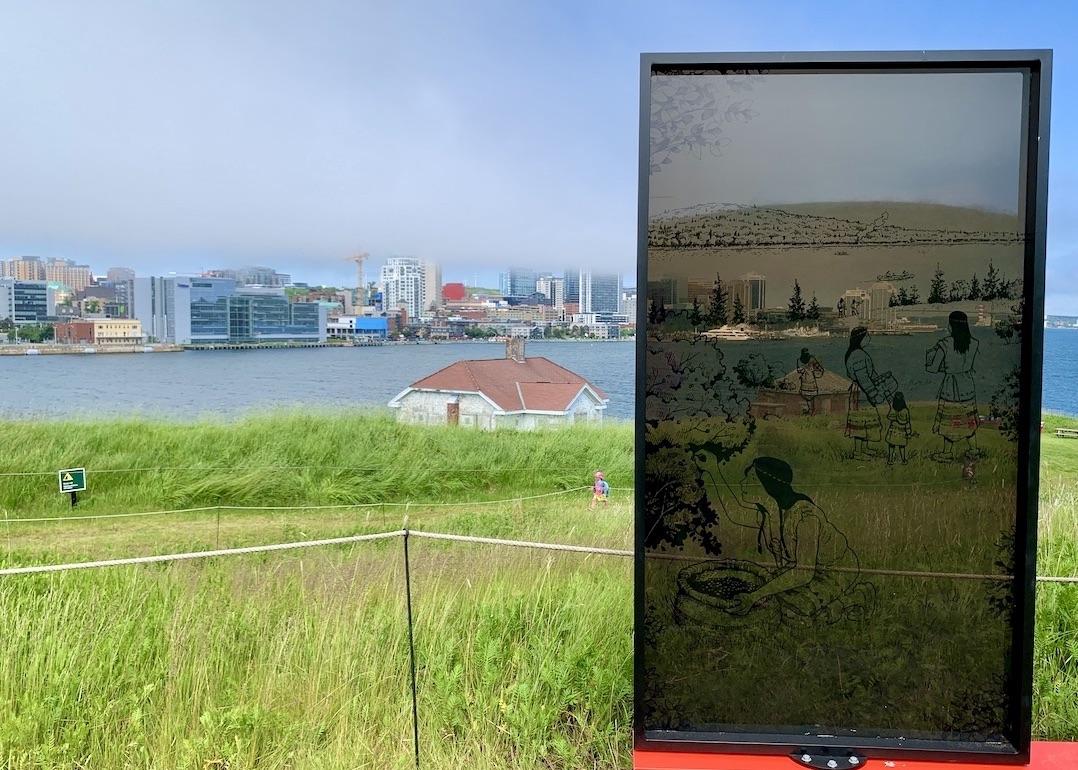

Parks Canada tells the story of the Mi'kmaq people who came to Georges Island long before the military/Jennifer Bain

This time I do book a ferry ride with Ambassatours and order a Parks Canada Perfect Picnic (a ploughman's lunch instead of the popular lobster roll — thanks to an allergy) to eat on the island. Parks Canada staff greet the ferry and direct us along an uphill walking trail, past the composting toilet, to the ruins of Fort Charlotte. An interpreter in World War II uniform leads a brisk tour of the subterranean maze of tunnels under the fort and then presides over a table of uniforms, gas masks, archival photos and other artifacts.

As I tuck into my picnic, I study a new, glossy brochure for a self-guided tour of Georges, marvelling at what a difference funding makes to a historic site. Modern interpretive panels describe how the Mi’kmaq started coming to Kjipuktuk (the Great Harbour) more than 1,000 years ago to gather and harvest its bounty, and how the island evolved to protect the city during the World Wars. Georges served as the city’s first prison and an internment camp for Acadians from 1755 to 1763 when the British captured, detained and deported about 900 people.

Enjoying a Parks Canada picnic on Georges Island with the Halifax skyline and Kawartha Spirit ferry in the background/Jennifer Bain

Georges has been a national historic site since 1965 but it took until 2020 to create a public wharf and open the island for regular, seasonal visits and not just sporadic events like concerts and weddings. As I sit in one of Parks Canada’s famously photogenic “red chairs” for my picnic, a garter snake slithers by just like at Fort McNab. This one ignores me.

This tiny island is famously home to hundreds of these snakes, who have reportedly inbred to the point that their markings and colorings are strikingly different from those on the mainland. I don't yet know this, or realize that it's actually somewhat rare to spot a snake here, so I only take one photo and let it go on its way.

There's no sign of the voles that the snakes love to feed on, but it's clear that herpetologists should come and study this unique population.

A garter snake at Fort McNab National Historic Site on McNabs Island/Jennifer Bain

Two days later, I'm in a van heading out of the city to see more of this Atlantic Canadian province's national historic sites and national parks. Krista Lingley, the Parks Canada promotions officer for Mainland Nova Scotia, hands me a brand new "Explore History in Halifax" brochure that explains, for the first time, the scope of the Halifax Defence Complex in a new push to get visitors to visit more than one or two sites.

Lingley is eager to see McNabs and Georges play a bigger role in the city's expanding waterfront experience. She has a blog post ready to go that details the various ways you can get to all five spots, while of course "managing expectations of what there is to do at these locations."

Comments

I highly recommend visiting Halifax--I did so for the first time just prior to the Covid Pandemic and thoroughly enjoyed the history, music and fish & chips. Conveniently it's the eastern terminus of Canada's superior ViaRail system--itself an experience to travel across Canada. I did not visit McNabs Island however, the Citadel is located in the center of Halifax. Wonderful city and wonderful folks. PS: Halifax is also a freighter terminal to Liverpool, England so take a good book if you continue eastward.

WONDERFUL article!!!