Visitors to Covehead Lighthouse at Prince Edward Island National Park are kept off the sand dunes on the path to the beach/Jennifer Bain

Protecting P.E.I.'s Sand Dunes From Footsteps

By Jennifer Bain

The five-word message flashes urgently on a solar panel sign mounted on a trailer parked by the Prince Edward Island National Park entry kiosk.

“Please stay off the dunes.”

This isn’t the time or place to delve into the details — not while there are park fees to pay and campground maps to secure — but different versions of this key message will pop up at every turn throughout the seaside park.

“Healthy dunes make healthy beaches,” reads the wordiest sign. “All sand dunes are environmentally sensitive areas. Please do not walk or climb on the dunes. Use designated beach access paths only. Thank you for your assistance in preserving this key natural feature of Prince Edward Island National Park.”

“Entry into dunes is restricted,” reads the sternest sign, with an image showing dune boundaries marked in red. “Minimum fine is $150. Stay off all dunes.”

“Dunes are damaged by foot traffic,” reads a sign that hints at the “why” behind the directive. “Please stay off dunes and use designated paths only. You can help keep the dunes healthy!”

“Stay off dunes,” reads the shortest message.

Walking on P.E.I. National Park's sand dunes has been banned since 2021/Jennifer Bain

Some 800,000 people a year (pre-pandemic, at least) come here to the north shore of Prince Edward Island to swim in the Atlantic Ocean, relax on sandy beaches and admire spectacular sand dunes. So why can’t we all kick off our shoes and race up and down the hot dunes like I did one summer decades ago?

Ten footsteps — that’s why.

That’s all it takes to harm the marram grass that’s holding these “fragile giants” together. Marram grass — one of the few plants that can survive this desert-like area — can tolerate salt, sun and sand. But it can’t hack being trampled by humans or vehicles. Footpaths on the dunes can break the plant’s roots, cut part of the delicate web and potentially cause an entire section of the dune to blow away or at least become more susceptible to erosion from storms.

Lindsey Burke, a Parks Canada resource management officer with the P.E.I. Field Unit, stands in front of dunes protected by a boardwalk, fencing and signs/Jennifer Bain

Stabilized dunes, on the other hand, can become home to a diversity of plants and provide better habitat for insects. This attracts nesting birds, small mammals and larger predators like coyotes and red foxes while providing a crucial barrier from strong winds and storm surges along the coastline.

“Personally, I love the dunes and there are lots of special plants that only grow on them,” says park warden Doug Campbell. “It’s kind of a special place and people don’t always realize that until they slow down.”

I’ve come to this national park to do a deep dive into dunes. But first I have to wrap my mind around the geography of this three-part park.

I'm the first person to try this Bunkie, a cabin with heat and electricity, at Stanhope Campground/Jennifer Bain

The Brackley-Dalvay section, where I spot the first flashing message, is the closest to Charlottetown. It’s 25 kilometres (15 miles) northwest of the provincial capital and offers sandy beaches and the photogenic Covehead Lighthouse. It’s here in Stanhope Campground where I spend two nights testing one of the park’s new Bunkies — tiny cabins with electricity, propane heat and a bunkbed — and where I feast on sticky date pudding in the MacMillan Dining Room at Dalvay by the Sea, a national historic site and hotel.

It’s another five kilometres (three miles) to the park’s Cavendish-North Rustico section, which has its own entry kiosk and solar panel sign and also boasts sandy beaches plus sandstone cliffs. This area is ground zero for all things Anne of Green Gables, including Green Gables Heritage Place and the Site of Lucy Maud Montgomery’s Cavendish Home.

P.E.I. National Park hits visitors with dune protection messaging right when they enter/Jennifer Bain

The final piece of the park — Greenwich — is off on its own, 60 kilometres (36 miles) east of Charlottetown. It doesn’t have a campground but is known for its dunescapes and Mi’qmaq/Acadian heritage.

At the Greenwich Interpretation Centre, I learn why the dunes are unique and worthy of protection. Enormous quantities of sand move from offshore bars to beaches to dunes and back to offshore bars in an annual cycle. Severe storms dramatically alter the dunes and beaches. Even in good weather, wind, waves, currents and rising sea levels keep the sand continually on the move.

Greenwich has one of Canada’s two coastal parabolic dune complexes. Rare in North America, these dune complexes can also be found in Quebec’s Magdalen Islands and in the United States at Cape Cod and along the Pacific Northwest coast and Lake Michigan.

The Greenwich dunes form a giant, U-shaped parabola that’s nearly one-kilometre (0.6-miles) wide and 20-metres (65-feet) tall. They’re renowned for the gegenwälle (counter ridges) that form inside the U as the dune migrates downwind.

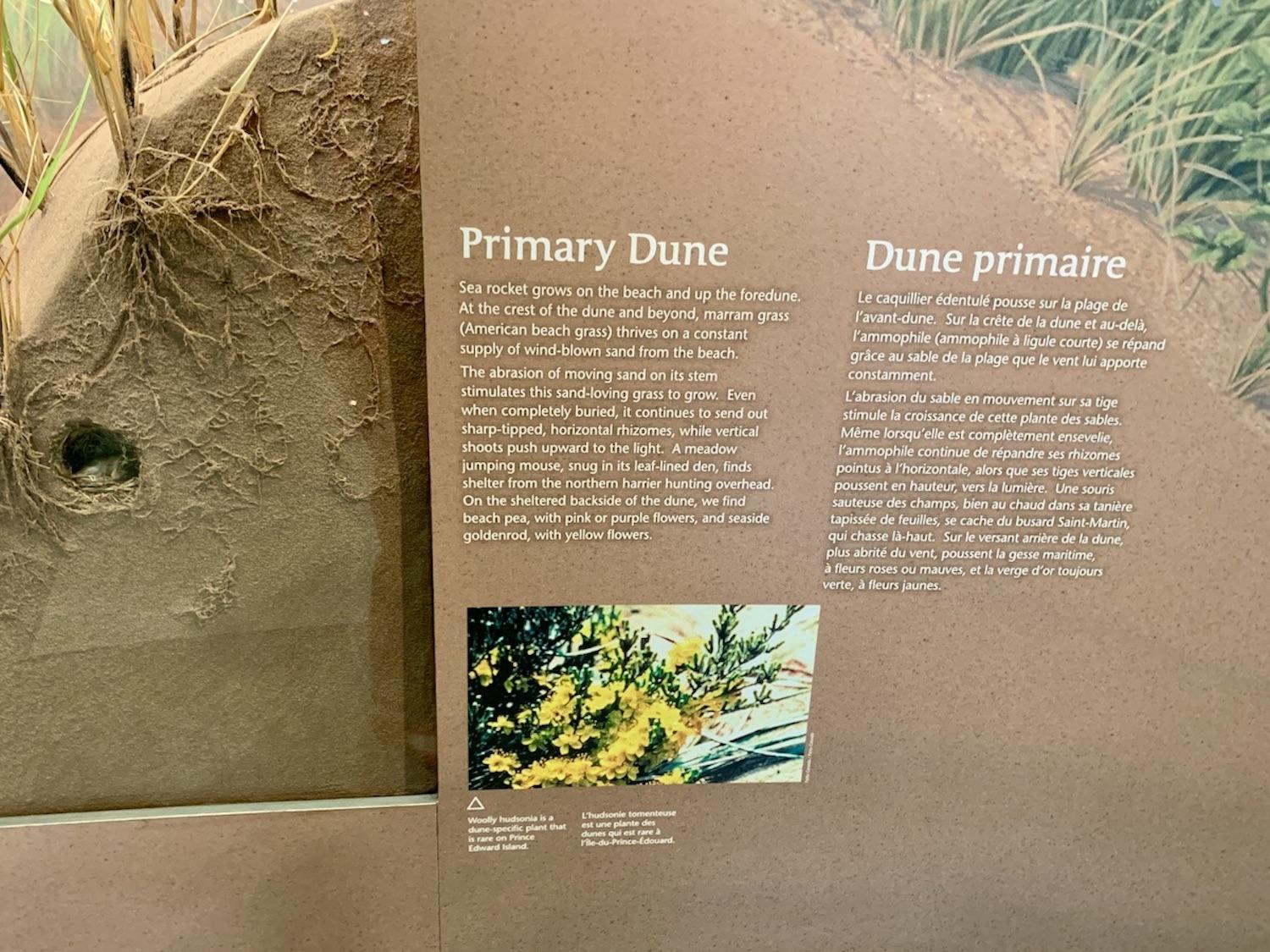

An exhibit at the Greenwich Interpretation Centre shows the root system of marram grass/Jennifer Bain

Marram grass helps create the gegenwälle. Seedlings become established between the base of the dune and the low-lying wet slack in front of it, where growing conditions are ideal. The grass holds the sand and creates the first ridge. As the dune moves downwind, another spot is created between its base and the slack. This stabilizes the sand, creating a new ridge. This process repeats, eventually creating the banded pattern of ridges known as gegenwälle.

Rilla Marshall, the visitor services team lead at Greenwich, says P.E.I. (famously home to potatoes and other crops that love its rich, red soil) is the most developed landscape in Canada and the most densely populated province. It doesn’t have large areas of wilderness, making the national park all the more precious. Marram grass was once harvested by French settlers to feed their cattle. British farmers let their cattle graze on the dunes until the mid-1900s. In the 1950s, a large fence was erected here to slow moving sand, and while it may have worked it also altered the landscape.

Rilla Marshall is the visitor services team lead at the park's Greenwich section/Jennifer Bain

“People have tried to control sand movement and stop coastal erosion in the past,” notes Parks Canada on an interpretive sign. “Today, there is general recognition that this system is beyond our control. Parks Canada lets nature take its course in Prince Edward Island National Park.”

Kerry-Lynn Atkinson, a landscape ecologist with the park, says “dunes literally are a natural shield and barrier against climate change and erosion impacts” and staff have spent decades preserving and protecting them.

Special "stairs" over a dune at the end of the Greenwich Dunes Trail/Jennifer Bain

They have identified spots impacted by humans and earmarked them for restoration work every fall. They have planted marram grass plugs, moved and created boardwalks and laid down truckloads of discarded Christmas trees to help repair and protect the dunes. Atkinson says the park reluctantly decided in 2021 that the “best way to protect our dunes is to close them.”

Warning signs and roped-off areas make sure people look at, but don’t touch, the dunes.

The best place to view the dunes is along the Greenwich Dunes Trail. Most of the 4.6-kilometre (2.8-mile) long trail is smooth, packed gravel but there are wooden boardwalks over sensitive areas. The one-way trail ends with a floating boardwalk over Bowley Pond to a viewing platform in the dunes. A sand ladder and special matting act as a staircase to help people cross a steep dune to the beach.

A view of the floating boardwalk on the Greenwich Dunes Trail/Jennifer Bain

The popular trail is unexpectedly closed for boardwalk repairs when I visit, so I have to hike down the beach and then climb a wooden staircase up the steep dune to get down to the portion of the floating boardwalk that isn’t being worked on. It’s worth the extra effort.

During three days in the park, I don’t spot anyone flouting the sand dune rules.

Campbell, the park warden who’s with the Law Enforcement Branch of Parks Canada, says they deal with 15 to 20 dune incidents each year. This includes seeing footprints after the fact, but mostly giving verbal and written warnings and issuing tickets. The Park Compliance Team patrols the park providing educational messaging.

“Most people are very understanding of the need to stay off our dunes,” allows Campbell. “We often get reports from visitors who see people on dunes, and they are very appreciative that we take action to help protect them.” Education, he says, “goes a long way to get people to buy in.”

Citizen scientists can upload "coasties" at two park spots to help monitor coastline erosion/Jennifer Bain

Speaking of education, visitors can play citizen scientist at “coastie” stations set up on Cavendish and Brackley beach. You put your smartphone in a designated cradle and snap a photo of the coastline to help Parks Canada monitor coastal changes. (The word coastie is a play on selfie.) The University of Windsor will then analyze shoreline retreat, dune erosion and recovery, storm surge and ice cover, vegetation structure, beach use and rip current locations.

And if you’re wondering why dogs are banned along this park’s beaches from April 1 to Oct. 15, it’s to protect Piping Plovers. The endangered shorebird nests on the beach, where people, storms, foxes, raccoons and pets are a threat to its nests, eggs and chicks.

This Bank Swallow nesting site at Cavendish Campground and beach is protected/Jennifer Bain

Bank Swallow nesting sites are also protected here in a seaside cliff in Cavendish Campground. The species at risk lays eggs in tunnels dug into the cliff face, which is an open area with plenty of the flying insects they feed on. Bank Swallow populations have apparently declined in Canada by 98 per cent in 40 years, and these cliffs are eroding due to severe weather events linked to climate change.

“Climate change is the defining issue of our time,” says Parks Canada. As the effects of our warming planet become more visible, this park looked to the first caretakers of this land — the Mi’kmaq people — for guidance.

Outreach officer Bob Harding explains how the Park Promise works and how they gather visitor promises in Mi'qmaq baskets/Jennifer Bain

Outreach officer Bob Harding explains that a 17-line Park Promise was developed in collaboration with P.E.I.’s poet laureate Julie Pellissier-Lush, a knowledge keeper from Lennox Island First Nation. Built around the seven directions/sacred teachings and meant to be sung, the promise speaks to things like loving the flora and fauna, keeping the sky clean and leaving the park the way we found it.

The park collects wildflower seeds and embeds them in tiny pieces of recycled paper. Visitors are asked to write a message and place their “promise” in a Mi’qmaq basket. The messages are passed on to the resource conservation team and planted where needed.

“If you see wildflowers, they’re likely somebody else’s promise — or even your own,” says Harding.

And the messages? They’re things like “I promise not to litter,” “I promise to help others” and — naturally — “I promise not to walk on the dunes.”

Add comment