How Horace Kephart Found His 'Back of Beyond’

By Aaron Searcy, GSMA publications associate

By the springtime of 1904, Horace Kephart’s life was falling apart.

In a desperate note pressed into the hands of his bartender, he wrote that he was being “driven by devilish torments.” His plight was “spiritual rather than mental,” he claimed. “The story, if published, would be considered the ravings of an imbecile.”

Soon after passing off this note, Kephart stepped out into a St. Louis street and proceeded directly toward a nearby bridge with intentions of jumping into the Mississippi River far below. Only moments before the tormented man could do the unthinkable, a police officer stopped him short and safely escorted him to a hospital.

Within hours, local newspapers reported the dramatic story of Kephart’s breakdown and published his hastily written note in full alongside witnesses’ accounts. As the news spread, Kephart remained confined and under medical supervision until his closest family could come to collect him and take him home.

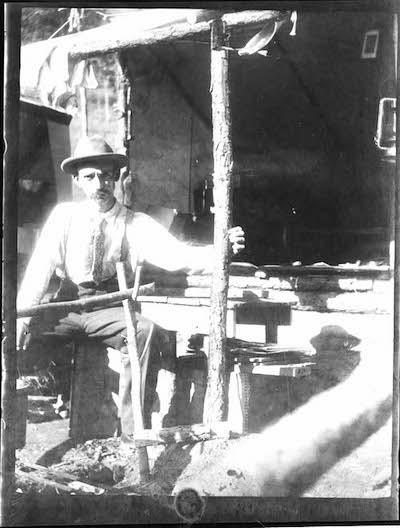

Although he pursued a career as a librarian for much of his early life, Horace Kephart mastered the art of backcountry living. His two-volume set Camping and Woodcraft remains one of the best-selling sporting books of all time/Image from Horace Kephart Family Collection, courtesy Great Smoky Mountains Association.

Less than a year prior, the 41-year-old married father of six had held an esteemed position as the head of a library in St. Louis, where some coworkers openly considered him a genius. Beyond his professional role and notable status, Kephart could claim Yale and Cornell on his resume along with bylines in some of the country’s most prominent magazines like Harper’s and Forest and Stream.

His well-researched and often-humorous articles reflected a wide range of interests, but the core of his work was driven by his deep fascination with the art of life in the wilderness and the people who made their lives there. Often setting out by train to escape the city, Kephart had sought a place of refuge in the comforts of the Ozarks where he could relax, make camp, and indulge in his favorite pastimes including woodcraft, cooking, and riflery. It was this kind of refuge found within the natural world that he would come to refer to as his own “back of beyond.”

But even with these reprieves to live “the simple, natural life in the woods, and leave all frills behind,” as put by his literary mentor George Sears under the penname “Nessmuk,” the strain of life in the city proved all too much for Kephart.

In the months before his breakdown, Kephart’s frequent absenteeism at work ultimately cost him his job. Compounding financial worries and trouble with alcohol soon led to the deterioration of his family life as well. With his young children and wife, Laura, retreating to stay with family in New York, Kephart settled in a boarding house and began working himself ragged to complete a book of his own.

The culmination of years of work, that book project would eventually see the light of day as The Book of Camping and Woodcraft (1906). In fact, it would go on to become one of the best-selling sporting books of all time as an expanded two-volume set retitled Camping and Woodcraft (1916–17). But before Kephart could complete it, he would have to overcome his painful, life-shattering breakdown in the spring of 1904. And after a summer spent recovering at his parents’ home in Ohio, he would also have to leave his career and life in the city altogether to take up residence in the shadow of the remote Smoky Mountains.

Horace Kephart in an iconic portrait taken in the Smokies by his friend and fellow park-advocate George Masa/Image from Horace Kephart Family Collection, courtesy Great Smoky Mountains Association

It was in the Smokies that Kephart found himself and found his inspiration, and it was here that he completed his first masterwork on woodcraft. Several years later, Kephart produced a second commercial success with Our Southern Highlanders (1913). In the decades that followed, Kephart brought national attention to the Southern Appalachian region and became one of the fiercest proponents for saving the Smokies from further destruction at the hands of the logging companies.

“I owe my life to these mountains,” Kephart wrote years after his breakdown in St. Louis, “and I want them preserved that others may profit from them.”

In Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography (2019), co-authors George Ellison and Janet McCue unravel the complicated story of how this wayward librarian at the end of his rope finally found his refuge in the mountains and, in the process, became a champion central to the formation of the Appalachian Trail and Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

“As it should, the biography provides for the first time an understanding of Horace Kephart’s entire life—not just random bits and pieces such as those often heard in conversation, many of which are anecdotal or outright fabrications,” said Ellison, a writer-naturalist who has lived near Kephart’s eventual chosen hometown of Bryson City, North Carolina, since 1973.

While Kephart wrote several books and left hundreds of articles and letters, piecing together the more personal aspects of his life required decades of research and deep dives into the lives of his closest family members and confidants.

“Kephart is a man full of contradictions—solitary yet a masterful storyteller; generous yet indebted; conventional yet unconventional; a loyal friend and an absent parent,” said McCue, whose professional life as a librarian at Cornell University tied her to Kephart, who’d been a graduate student there in the early 1880s. “He explains in his autobiographical sketch ‘Horace Kephart by Himself’ that ‘much else has been left out.’ Given this natural reticence, much of his story is of necessity revealed by others—an ensemble cast of friends and family who help flesh out his fascinating character and personality.”

Back of Beyond: A Horace Kephart Biography compiles decades of research to tell the story of a man central to the creation of the Appalachian Trail and Great Smoky Mountains National Park/Great Smoky Mountains Association.

Riding a wave of renewed interest in Kephart, Back of Beyond received the coveted Thomas Wolfe Memorial Literary Award upon its release in 2019. Soon after in 2020, the University of Tennessee published Horace Kephart: Writings—an expansive collection of Kephart’s correspondence, articles, journal entries, fiction, and manuscripts co-edited by Mae Miller Claxton and George Frizzell. McCue is now working with the Asheville-based filmmaker Paul Bonesteel on a forthcoming Great Smoky Mountains Association biography of the photographer George Masa, another champion of Great Smoky Mountains National Park and a close friend of Kephart’s.

In addition to Back of Beyond, Great Smoky Mountains Association has published Kephart’s history of Cherokee removal in Southern Appalachia The Cherokees of the Smokies (1983), his previously unpublished novel Smoky Mountain Magic (2009), and expanded and new editions of Kephart’s most well-known works Camping and Woodcraft (2011) and Our Southern Highlanders (2014).

All these titles are available in Great Smoky Mountains National Park visitor centers and online at SmokiesInformation.org. All proceeds from the sale of the books benefit the educational, historical, and scientific programs of Great Smoky Mountains National Park.