An endangered Pacific fisher, a key species at Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. / NPS

Mapping The Web Of Life

The national parks protect immense biodiversity, and science is providing the data and graphics to monitor and protect that biodiversity.

By Kim O’Connell

Long and wily, with eyes like onyx marbles and ears like half-moons, the Pacific fisher is like several animals in one. A member of the weasel family, the fisher pads along stealthily like a cat. It climbs trees like a bear. It has glossy fur like a muskrat and a long tail like a marten. Like rabbits and rats, fishers are often crepuscular, most active at dawn and dusk. It is often solitary like a skunk. Like cougars and wolves, the fisher is tough enough to prey on porcupines. And yet for all their commonalities with other creatures, fishers are still lesser-known mammals—and quietly disappearing from parts of their historic range.

Worldwide, the fisher is still plentiful enough to be considered a species of “least concern” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). But in California, the southern Sierra Nevada fisher population has suffered from widespread habitat loss, tree mortality, and depletion from 19th- and 20th-century trapping, enough so this specific population is now listed on both the state and federal endangered species list. This makes the populations that remain within Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks even more critical. Not only is the population small (just a few hundred individuals) and dispersed, the species also has low genetic diversity, which inhibits long-term survivability.

“The primary reason [the fisher is endangered] is extensive tree mortality,” says park biologist Tyler Coleman. “We’re having massive climate-driven drought mortality. We have years of tree loss, and then we had a major fire last year”—the KNP Complex fire, which ultimately burned more than 88,000 acres and 16 sequoia groves—“so the fisher is not doing well.” In a 2013 natural resources report for Sequoia and Kings Canyon, for example, the National Park Service noted that the “long-term conservation of [the fisher] in the parks will only be accomplished in conjunction with efforts to protect this species and its habitat in the region.”

The fisher is just one of more than 70 mammal species at Sequoia and Kings Canyon, one of the most biodiverse national parks in the system, with more than 200 bird species, 14 amphibian species, and 21 reptile species. Other national parks are also prized for their biodiversity—including Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, the Everglades, Big Bend, Great Smoky Mountains, Glacier, and others.

Yet according to the U.S. Geological Survey, only about 13 percent of land in the United States is protected for biodiversity, leaving thousands of plant and animal species vulnerable to a range of threats—from invasive species to habitat loss to a changing climate. Meeting this challenge is often dependent on available funding, staff, and partners, and increasingly, sophisticated data that looks beyond park borders.

Mapping Biodiversity and Needs

Biodiversity data has been gathered for a long time, but it’s getting more precise and detailed, and therefore more useful for public agencies, scientists, and conservationists. To address biodiversity concerns within the system, the National Park Service has a Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Division, which includes departments focused on biological resources as well as inventory and monitoring (I&M). NPS maintains 32 I&M Networks nationwide that conduct research that informs conservation approaches on an ecosystem level. Recent inventories at Sequoia and Kings Canyon, for example, have revealed new information about the parks’ bat diversity, including documentation of the 17 species of bats that occur in these parks. In Yosemite, hundreds of wildlife species have been identified, as well as more than 1,570 vascular plant types. Glacier National Park has at least 1,132 species of vascular plants, and the Everglades boasts well over 350 types of birds. (The Traveler reached out to the NPS Natural Resources Division, the NPS Biological Resources Division, and the NPS communications lead in Washington and did not receive a response for this story.)

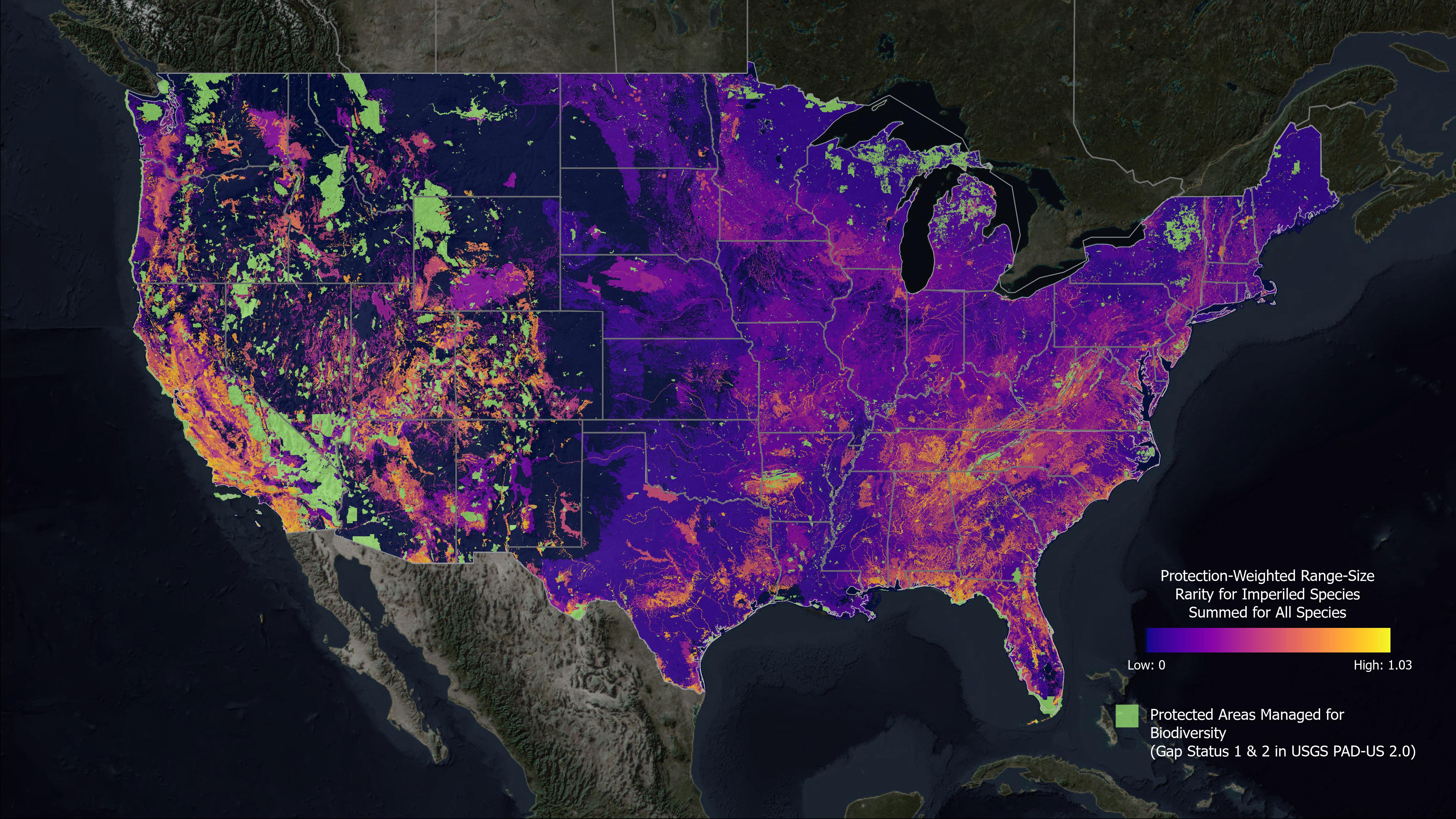

This map displays the distribution of 2,216 of the most imperiled plants and animals in the United States. Brighter colors indicate where land and water protection would provide the greatest benefit for the most threatened areas of biodiversity. Green denotes areas that are currently protected for biodiversity, including national parks. Note the concentrations of threatened biodiversity in areas like southern California, the Colorado Plateau, and the southern Appalachians. / NatureServe

Scientists at NatureServe, a nonprofit research organization, have conducted several mapping and data-gathering projects related to biodiversity, including ongoing work with state natural heritage programs and federal agencies including NPS, as well as international organizations like the IUCN. Recently, they mapped the locations and habitats for 2,216 imperiled species nationwide, providing a detailed visual representation of our most biodiverse areas and those with the greatest needs for protection. Most lie outside the national parks, illustrating the pressure on the parks to serve as refugia for imperiled species and to partner with organizations and entities outside their boundaries.

What’s also important about this new map is that, unlike previous similar studies that focused heavily on vertebrates, the map acknowledges that more plants are imperiled compared to animals, and that both plants and invertebrates are provide nutrient cycling, water purification, and pollination to ecosystems, according to NatureServe. This project is the first high-resolution map that includes such a taxonomically diverse range of species, including more than 1,600 imperiled plants.

“The nature of biodiversity is that you have to map it because it is spatially related to each other,” says Dr. Sean O’Brien, president and CEO of NatureServe. “The way the different species lay out on the landscape and how that creates different kinds of habitats and ecosystems—if you're not mapping it, you really don't know what to protect, because you don't know where it is.”

In a paper about the mapping effort published in the journal Ecological Applications, NatureServe scientists reported that suitable habitat for 295 imperiled species falls completely outside of protected areas, 1,029 imperiled species have at least 10 percent of their distributions in protected areas, and 225 of these occur mostly or entirely within protected areas.

“Established protected areas clearly have a major role to play in protecting U.S. biodiversity,” the authors wrote. “Over one-half of the imperiled species studied are likely to occur inside protected areas.”

The map shows areas of high biodiversity need throughout California (near areas like Yosemite and Joshua Tree national parks), the Colorado Plateau (Zion, Grand Canyon, Grand Staircase-Escalante), and the southern Appalachians (Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains).

“There’s an enormous amount of data to feed into priority setting at a national scale,” says Pat Comer, NatureServe’s chief ecologist. “But it's important to recognize, you know, how do we define protection? It's actually a much more complex picture out there. There are those places that are fairly straightforward, with a mandate for conserving the resource, like a national park. Then there are multiple-use public lands, like a national forest, where there has to be a lot of public input into determining what actually can happen on those areas. Then there's a lot of private lands where some very strong conservation actions are happening.” In the face of cascading climate-related shifts and increasing development, cross-boundary approaches are required.

Genetic Diversity in a Changing Climate

When it comes to crossing boundaries, a potential model for biodiversity protection is the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, a nearly 2,200-mile footpath that traverses 14 states and provides the longest vegetated corridor in the heavily populated Eastern Seaboard. The Appalachian Trail Conservancy, the NPS’s main nonprofit partner for the trail, is increasingly focused on biodiversity protection efforts throughout the corridor, working with federal, state, local, and private entities.

Wildflowers near the Appalachian Trail on Roan Mountain, North Carolina. / Ken Lane

“Ecological restoration and habitat resiliency are growing priorities for the ATC and our partners, partially because the A.T. corridor is critical refugia for protecting biodiversity,” says Marian Orlousky, ATC’s director of science and stewardship. “Part of it is the nature of its linear corridor and that it crosses ecoregions. We work to identify biodiversity hotspots, places with really rich biodiversity or a major emerging threat.”

This work currently includes protecting large ash tree stands in the corridor, to the extent possible, from the invasive emerald ash borer and removing culverts on streams in Maine that block Atlantic salmon access. “The challenge of focusing on ecological resiliency across a large landscape is limited resources,” Orlousky adds. “Understanding what we have now, a little climate planning and scenario planning, and then putting our limited resources towards those locations.”

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is taking a similar approach to protecting the biodiversity in this famously biologically rich park. Great Smoky has been the laboratory for a major ongoing species inventory, the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory, which has been conducted by the nonprofit Discover Life in America since 1998. Since the inventory’s inception, the known species list in the park has grown from about 10,000 species to more than 20,000 species, which includes more than 1,000 species previously unknown to science. And yet, scientists believe the park might shelter up to 80,000 plant and animal species, so much work remains to be done.

On top of this, the park regularly partners with outside researchers on specific projects related to biological science. The goal is to protect not just biological diversity but genetic diversity, says Paul Super, science coordinator for the NPS Appalachian Highlands Science Learning Center, located just outside the park.

“If you’re looking for the genetic diversity from bellflowers to downy woodpeckers, you should come to the Smokies,” Super says. “If you go to Alberta, the downy woodpeckers are much less biodiverse than the ones in the southern Appalachians. When we’re trying to protect biodiversity, we’re not just trying to protect species, because downy woodpeckers are found throughout North America, we’re trying to protect this genetic diversity, which could be important for that whole species to survive changing climates or whatever sort of stressors could exist in the future.”

Recent research has focused on brook trout, coneflowers, salamanders, and pollinators. “We use genetic diversity as a way to monitor the health of a species that’s hard to monitor, such as salamanders, which spend most of their time underground,” Super says. “For plants, botanists might visit five or six locations around the park, at different elevations and drynesses, collect a number of samples like a paper punch of a leaf, and preserve them in a test tube. They might look at a couple regions on the chromosome and see how much variations there are on the chromosome. Most of what they’re doing is work in the lab.”

NatureServe has an ongoing partnership with NPS to produce vegetation maps and natural resource inventories for each park, as well as documents that assess general biodiversity health and trends at various national parks. Recent projects with the parks include ongoing vegetation inventories at Mojave National Preserve, an ecological restoration guidance document for sagebrush habitat at Colorado National Monument, and a climate change analysis for different habitats within the developed and fragmented parks of the National Capital Region.

“It’s been a challenge to develop the baseline information in the first place and then to have the kinds of challenges that we're facing in terms of accelerating climate change,” Comer says. “I've been doing this for over 30 years and, and we are increasingly able to observe and develop extremely high-resolution map products. And so we're going to see another kind of a revolution of mapping happening over the next 10 years that at least is going to help us cope a little bit better with this challenge….And so that gives me a lot of hope.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places