The white puffs are evidence of hemlock woolly adelgid infestation. / Michael Montgomery, USDA Forest Service

Forest Keepers

The National Park System is an essential laboratory—and also a battleground—in the management of invasive pests.

By Kim O’Connell

Editor's note: National Parks Traveler in a long-running series has been reporting on invasive species, both flora and fauna, in the National Park System, and on efforts to combat them. In the following article Kim O'Connell looks at efforts to thwart invasive beetles from killing tree species in park forests.

GATLINBURG, Tennessee -- It’s a misty morning in Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Fog laces through the trees on either side of the park road as I head towards my destination, the Twin Creeks Science and Education Center, a National Park Service facility on the park's Tennessee side. All around me is a forest so lush and dense it feels like something out of a fairy tale—a mix of hemlocks, pines, maples, oaks, and countless other species. Inside Twin Creeks, however, a different story is being told, a story of scientists at work: Maps and charts depict vegetation types and different data sets on the park's forest health, and bookshelves are heavy with scientific reports and conference proceedings.

As the park's supervisory forester, Kristine Johnson knows the park's trees pretty well—and not just species, but sometimes individual trees. She was hiking in the park this past summer when she came across a notable Carolina hemlock tree that had fallen. A fellow ranger had already cut the tree to clear the trail and, in doing so, had counted the rings back to 400 years.

“It’s not unusual to see hemlocks that are 400, 500 years old,” Johnson tells me, adding that eastern hemlocks routinely reach well over 100 feet in height. “The ‘redwoods of the East,’ they are called.”

Unfortunately, these oldest, largest hemlocks are highly vulnerable to a sap-sucking invasive pest called the hemlock woolly adelgid, which was first introduced to the eastern United States on infested horticultural material in the mid-1950s and has now caused extensive tree mortality and decline throughout the eastern species’ historic range. Like many other national parks and forests, Great Smoky Mountains foresters are working to protect the park’s trees from the growing scourge of invasive insects and tree pathogens. The park, considered one of the world’s most biodiverse, contains about 100 native tree species in total, and about 20 percent of its forests are old growth.

Park staff had previously treated this particular hemlock with pesticide, but it still didn't make it. “We have a lot of hemlock here and some of the park is hemlock-dominated, and many of those were old growth,” Johnson says. “Unfortunately, those old growth trees, they were our highest priority to try to save with the [pesticidal] tree injections and soil drenches that were becoming more available. And unfortunately, because they're very large and because they're old, they have impaired vascular systems, so the treatments didn't work as well. Simultaneously we had about three years of drought, and that really stressed the trees. We lost a lot of the trees that we tried to treat in Cataloochee, one of our best old-growth areas.”

Systemwide Challenges

Whether they are found in national parks, national forests, national grasslands, or other public lands, forests provide widespread ecosystem services, including oxygen, cooling shade, habitat and shelter, food sources, and the sequestration of carbon, which is ever more important in a changing climate. According to recent research published in the journal Nature Climate Change, forests absorb twice as much carbon as they emit.

"Forests are a major, requisite front of action in the global fight against catastrophic climate change—thanks to their unparalleled capacity to absorb and store carbon," wrote leaders of the United Nations Development Programme in 2018. "Forests capture carbon dioxide at a rate equivalent to about one-third the amount released annually by burning fossil fuels. Stopping deforestation and restoring damaged forests, therefore, could provide up to 30 percent of the climate solution."

Given their ecological importance, protecting forestlands from invasive pests and pathogens is a major challenge for public land managers like the National Park Service. In a 2016 study of the 25 most prevalent invasive animal species in the park system, five are insects—the red imported fire ant, the emerald ash borer, hemlock woolly adelgid, Lymantria dispar (formerly known as gypsy moth), and Africanized bees.

Hemlock woolly adelgid and its cousin the balsam woolly adelgid, emerald ash borer, and Lymantria have caused widespread destruction in places like Great Smoky Mountains and Shenandoah national parks, while trees in Point Reyes and Redwoods national parks have succumbed to sudden oak death, a disease caused by an exotic pathogen. Butternut trees at Mammoth Cave are threatened by pathogen-caused butternut canker, and white pines in Glacier and Sequoia are vulnerable to a disease known as blister rust. These current infestations were preceded by earlier invasions such as chestnut blight, which virtually destroyed all mature chestnut trees in America in little more than a generation in the early 20th century.

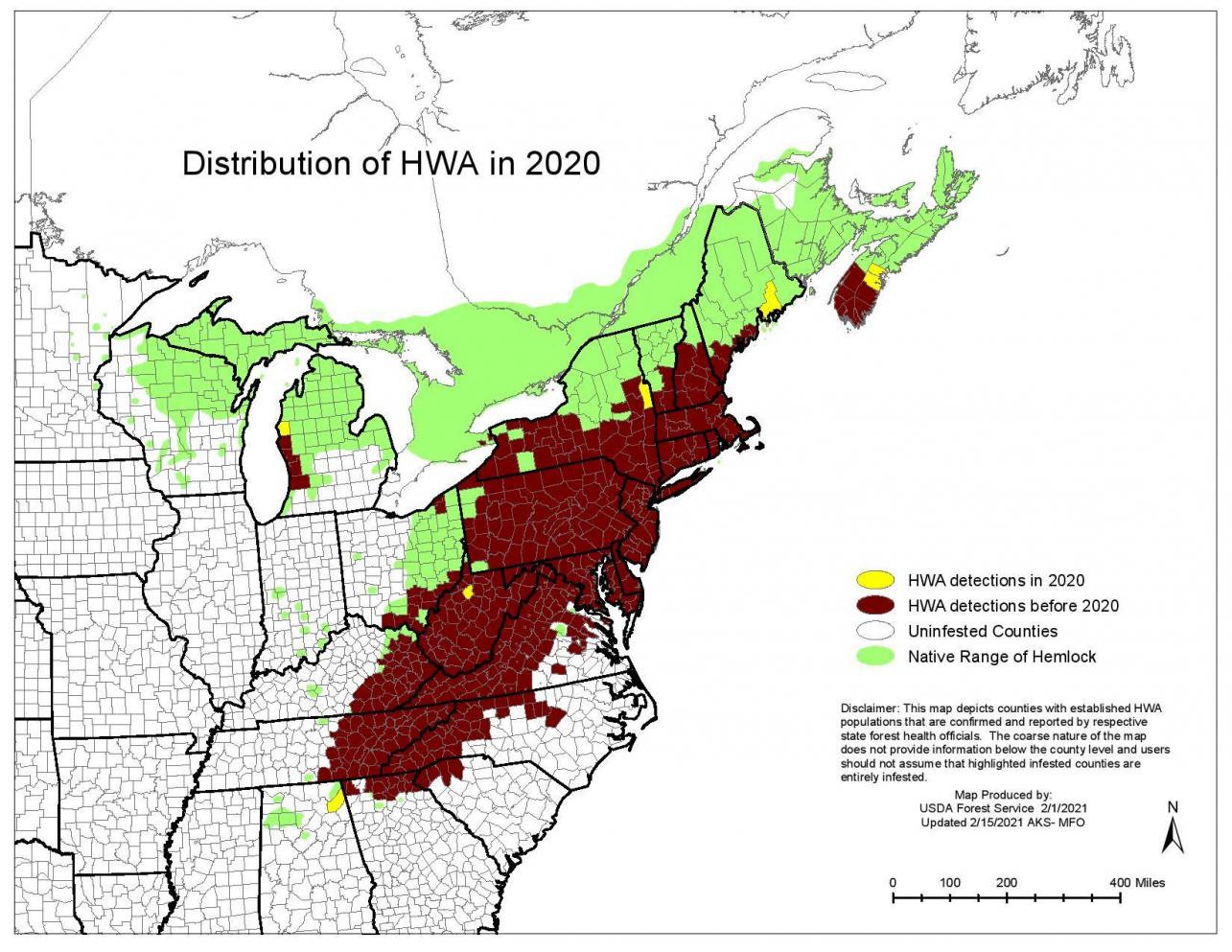

This 2020 map shows the widespread presence of hemlock woolly adelgid populations, covering Shenandoah in Virginia, Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee and North Carolina, and the Blue Ridge Parkway in between. / USDA Forest Service

In January 2021, the National Environmental Coalition on Invasive Species (NECIS), a consortium of nine nonprofit organizations, sent recommendations about invasives to the incoming Biden-Harris Administration. The recommendations noted systemic barriers to managing invasive species that include “inadequate funding, ineffective federal and partner collaboration mechanisms, and a lack of government-wide leadership. With compounding impacts brought on by wildlife and zoonotic diseases, plant pests, a changing climate, economic trade, and ecosystem degradation, this problem will only grow worse.”

“Like every other landscape [parks] are vulnerable to invasive forest pests,” says Erin Cadwalader, Ph.D., director of strategic initiatives for the Entomological Society of America, a NECIS member. “Despite their importance, national parks continue to be underfunded and thus struggle to defend against the myriad invasive threats that challenge them.”

Inventory, Monitoring, and Coordination

Another major challenge for park managers is propagule pressure, says Dr. Rebecca Epanchin-Niell, a senior fellow at Resources For the Future, a nonprofit think tank. Propagule pressure is the particular measure of invasive species introduced in a certain place and time. Epanchin-Niell served on an expert panel in 2019 that provided recommendations to NPS and published a widely cited paper titled “The unaddressed threat of invasive animals in U.S. national parks,” in the journal Biological Invasions.

“The national parks are located within a mosaic of landscapes, public lands and private lands,” she says. “National parks, when they have invasive species, are rarely able to control them on their own because, no matter what they do, chances are the species is also outside the national parks, so there is this propagule pressure. It’s important to me to understand how decisions are made with land managers outside the parks.”

Forested mountains along the Blue Ridge Parkway. / Kim O'Connell

Partnerships and coordination both within and without the park system are key. On a day-to-day basis, national parks use an integrated pest management approach that is ecosystem-protective, and the park system also engages in several ongoing multi-park monitoring efforts aimed at forest and ecosystem health, such as the Northeast Temperate Network (NETN), one of 32 NPS inventory and monitoring networks systemwide.

In a report published this past summer, Kate Miller, plant ecologist for the network, wrote that, “The bad news is that forests in NETN parks are threatened or already under attack by a number of serious stressors, including invasive plant species, deer overabundance, exotic forest pests, and climate change….In the short-term (years to decades), reducing non-climate stressors in parks, such as invasive plant species and exotic forest pests, is one of the best management actions park managers can take to ensure that forests are resilient for responding and adapting to a changing climate.”

NPS has also recently brought on a systemwide invasive species coordinator, Jennifer Sieracki. “The regional invasive animal coordinators and I have worked together to develop an action plan and funding prioritization plan to identify NPS’s most pressing needs,” she says. “This not only includes invasive animals control, but also identifies prevention, early detection, and education and outreach needs. Priorities also include providing tools and policies that make it easier for parks to manage invasive animals.”

The action plan includes recommendations from the 2019 Biological Invasions study and other reports, as well as expertise from the field, Sieracki adds. “This collective expertise provides a foundation for actions that are implementable within the NPS.”

At Great Smoky Mountains and elsewhere, implementable actions to deal with invasive pests have included both large-scale pesticidal treatments and biological controls. At Great Smoky, this includes the release of predator beetles that feed on woolly adelgids. Although the park can’t say it’s winning the war just yet, all these interventions help to slow the spread of invasive pests and help provide ongoing data to park scientists.

“It takes a very long time on a landscape scale to get that many insects out, to really exert an influence,” Johnson says. “The hemlock woolly adelgid population is going to have to come down to a lower level, either through genetic resistance or a combination of treatment, before biological control really be effective on the landscape.”

The park has some advantages, however. “We have tremendous biodiversity and that brings us resilience,” Johnson says. “We have competent managers who are always looking for what the next problem will be and trying to come up with the best strategies to address those both in prevention and treatment once pests are here. Constant vigilance, monitoring, and working with people in universities and other agencies are important, but there's a great biodiversity that we have here and a lot going for us.”

Hopeful Signs

Just outside Great Smoky Mountains, an orchard of chestnuts is providing hope and a potential path forward for keystone forest species. Scientists and organizations like The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) have been breeding hybrids of American chestnuts and the more blight-resistant Asian chestnuts. To date, TACF has bred more than 100,000 chestnuts on its research farm, and more than 500 research orchards are ongoing sources of scientific data and growth. TACF has worked with staff from Great Smoky Mountains and the Blue Ridge Parkway to collect wild American chestnut samples to support this ongoing work.

Leaders from the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and The American Chestnut Foundation sign an agreement to plant an orchard for chestnut restoration on Cherokee land next to Great Smoky Mountains. / Samantha Bowers, TACF

In April 2021, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and TACF signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that allowed the establishment of a demonstration orchard in the Qualla Boundary, the Cherokee land that abuts Great Smoky Mountains on the North Carolina side. The orchard will be a test bed for the restoration of the American chestnut, using local genetics, with the goal of producing seeds for distribution across tribal lands.

Outreach campaigns are becoming more vital to invasive pest control as well. In January 2020, NPS signed an MOU to be a partner in the PlayCleanGo program, spearheaded by NAISMA, the North American Invasive Species Management Association. This program encourages visitors to clean their gear, shoes, and clothing after hiking, boating, fishing, cycling, or other activities in a national park, to help prevent the spread of invasive insects and seeds. Some national parks, including Congaree in South Carolina, have installed boot brush stations to assist in the effort.

“The idea is we need consistent, positive marketing and branding across the U.S. and Canada on how people can clean their gear so they’re not spreading invasive species from the park to park or state to state,” says Tina Casagrand, a spokesperson for NAISMA. “The aim of the MOU [with NPS and other agencies] is to increase the reach of our prevention campaigns. We have signs that can be put on trailheads and other heavily trafficked public access points that remind people about things like weed seeds, spotted lantern fly eggs, and zebra mussels on your boat [that can spread easily].”

Despite the challenges, there are reasons for hope, Epanchin-Niell says. “If you think about so many of the invasive species on the landscape now, the hemlock woolly adelgid and others that are so widespread and problematic, they were introduced before we had policies in place to deal with them,” she says. “We have a lot more knowledge now. We have a lot more science. We have had successful biocontrol efforts….There’s a lot of people working on this problem—researchers, foresters on the ground, policy makers, from diverse perspectives and disciplines. It’s not something where we’re going to have an instantaneous fix. Everything that each person is doing is improving outcomes and helping to protect nature.”

Add comment