A Tiny Bug Is Upsetting Shenandoah National Park’s Ecosystem

By Kurt Repanshek

Editor's note: The spine of the Appalachian Range runs north and south through the Mid- and South-Atlantic states, a rumpled stretch of mountains that long has provided a corridor for species. One uninvited species, the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, arrived in 1951, and since then has attacked hemlock forests once commonplace in Shenandoah National Park, the Blue Ridge Parkway, and Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Since 1988 the National Park Service has been battling the tiny insect, and has met with varying success in those three parks. While much work remains to be done, there is optimism some of the hemlock stands will be saved. In the following stories, we take a look at the campaign.

Sunlight sifts through the forest’s canopy and falls upon our shoulders, easily penetrating an area of Shenandoah National Park once esteemed for its thick, almost ferny canopy, as Rolf Gubler and I amble down the Limberlost Trail.

Instead of towering, 100-foot (and even taller) Eastern hemlocks casting shade, we pass through sun-dappled thickets of black birch and underbrush dominated by mountain laurel.

Here and there a lone hemlock still stands, though there are the remains of over 1,000 of these magnificent trees, which once reached high into the sky in this pocket of the park. A non-native insect killed these trees, in just a few years, which led the National Park Service in 2003 to cut them down to keep them from falling on unsuspecting hikers. Now tree trunks and stumps line both sides of the trail, slowly moldering into the forest floor.

“We’re talking hundreds of thousands of trees,” says Gubler, a biologist who is the park’s forest pest manager, when asked how many hemlocks the park once held. Of those hemlock forests, “We’ve lost about 95 percent of our trees.”

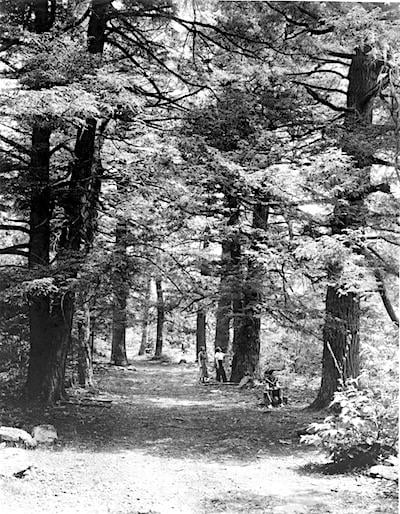

Hundreds of healthy Eastern hemlock trees once lined the Limberlost Trail in Shenandoah National Park/NPS

Once a stalwart of Eastern forests from Canada to Georgia, hemlocks thrive in low-light settings. They are renowned pockets of biodiversity, as their short, tightly spaced needles shade the understory and keep it from drying out.

Though not as long-lived as Bristlecone pines or sequoias (which can survive for 3,000-5,000 years) mature hemlocks nevertheless are no youngsters. They reach maturity in 250-300 years and can live another 500 years or so.

Hemlocks have long have been valued in the Appalachians, prized for their bark, which was sought by the leather industry for its tannins, and their pulp for use by the paper industry.

But in 1951 a speck of an insect, the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, was spotted in Virginia. It’s believed that the bug (which measures about one-16th of an inch long) hitchhiked to the United States aboard some ornamental plants imported from Japan. While it wasn’t considered a threat to Japan’s hemlock forests because of natural predators, and a natural deterrent in Asian hemlocks themselves, the bug has been devastating to hemlock stands in the Southeast.

What these insects do, essentially, is feed on the trees’ sap, “depleting the hemlock’s starch reserves, which in turn reduces the tree’s ability to grow and produce new shoots,” according to a 2004 report prepared by the U.S. Forest Service and the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.

Invasive species are steadily invading the National Park System, from zebra mussels that can kill native mussels and disrupt stream biodiversity; salt cedar (also called tamarisk) that overruns native willows and cottonwoods along river bottoms; emerald ash borers, which kill ash trees; and the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid.

Today the adelgids have impacted a long swath of hemlocks from Shenandoah through the Blue Ridge Parkway and deep into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina. The aphid-like adelgids were first noticed in the Blue Ridge Parkway in 2003, a year after they were detected in the Great Smoky Mountains. Efforts to rid the parks of the damaging insects have met with a range of results. For instance, the Blue Ridge Parkway might not need to chemically treat trees this year to stop the adelgids.

There are some parts of the National Park System in the Eastern United States where the insects haven’t established themselves. One is Mammoth Cave National Park in Kentucky, where graceful stands of hemlocks soar out of gorges in northern areas of the park.

Hemlock forests never dominated Shenandoah, but exist in pockets, unlike Great Smoky with its larger groves. The Limberlost area was one such pocket. This part of Shenandoah was so lush with hemlocks, some 3-4 feet in diameter, that they formed a sort of arboreal fairyland. Prior to the park’s establishment, George Freeman Pollock and his wife, Addie Nairn Pollock, saved 100 of the largest hemlocks that were growing here by paying loggers $10 per tree not to cut them down. (“Limberlost” was attached[K3] to the area by Mr. Pollock, who pulled the name from a novel about a young woman who lived on the edge of the Limberlost Swamp in Indiana.)

The impact of the adelgid infestation is easily visible along the Limberlost Trail. The forest canopy is patchy at best, and in places the trail tunnels through arching stands of black birch. Less visible are the impacts to the forest ecosystem. A healthy hemlock forest acts as a sort of humidifier for the forest, keeping temperatures cooler than forests with more open canopies, and sheltering moist soils.

The Hemlock Woolly Adelgid is easy to see on the underside of hemlock branches/Jane Schneider

“You have ferns and things like that and mosses growing in the understory, (it’s) very moist,” Gubler says as we survey the surrounding forest. “And you disturb that and then you’ve got hardwood species in here now.

“If you look around, look at the understory. It’s much drier. You don’t see ferns very much,” he continues. “You see a few. You don’t see as many mosses. In terms of stream water temperatures, you’re seeing increases in stream temperatures wherever we lose hemlocks along waterways.”

A bit further down the Limberlost Trail a bridge carries us across Whiteoak Canyon Run. Without the shade of hemlocks, the park’s thin creeks and streams warm easily under the sun’s rays, creating temperatures that impact the native brook trout.

“I think over time you’re going to see changes, species that exist there, things like brook trout. It’s going to have an effect on brook trout. They need cool water. They need shaded water with a high oxygen content,” the biologist explains.

Even bird species that normally flit through Shenandoah’s forests are affected by the adelgid. Blackburnian warblers, winter wrens, and Blue-headed vireos that prefer spruce/fir/hemlock forests are not showing up as often in bird surveys along the Limberlost Trail and around Rapidan Camp on the Rapidan River. Hardwood forests are taking over.

“The park’s just not offering that spruce/fir/hemlock dynamic that we used to be able to, so those species have to go elsewhere to find that mixture,” says Gubler. “We’re just seeing fewer of those specific birds.”

Park staff has aggressively been fighting the adelgid since 1996 with both chemical soil treatments and spraying. Last year, they introduced a predatory beetle native to Japan believed to only feed on the adelgid.

“The Laricobius nigrinus, which has been in use probably for the last 12 years, that species is pretty darn host specific,” the biologist says. “The new species that we’ve started to release in the park, Laricobius osakensis, that is very host specific to HWA, and we feel that that host specificity allows us to be pretty comfortable with using it as a bio-control.”

Before the beetles were available, park crews injected imidacloprid, an insect neurotoxin, into the soil for uptake into the hemlocks through their roots. They’ve also sprayed insecticidal soaps onto the trees.

Until the adelgid was first spotted in the park, in the fall of 1988, Eastern hemlocks covered roughly 9,800 acres of the park. After 2003, however, hemlocks remained in only about 500 acres scattered throughout the park. Since the park shifted to imidacloprid soil treatments in 2005, they have been able to treat roughly 2,000-2,500 hemlocks per year and reverse hemlock crown decline in many previously untreated areas (especially in more remote areas). When looking at treated hemlocks in the park now, they are healthier than they have been in the past 15-20 years.

“Over the last 10 or 12 years we’ve been doing soil injections of imidacloprid. We’ve treated about 24,000 hemlock trees,” says Gubler. “We’re on a seven- or eight-year treatment cycle, so I think we can certainly keep those trees preserved and protected over time. We hope to eventually switch over to bio-controls so we can get off of that pesticide cycle.”

To monitor the effectiveness of the program, crews check the health of hemlock crowns.

“We’re looking at the decline or the improvement of crown health in hemlocks. We do that by assessing the live crown of treated hemlocks over time,” explains Gubler.

Today there are perhaps 30,000-40,000 hemlocks of various sizes left in Shenandoah, a small number compared to the 800,000 or so hemlocks that existed before the adelgid arrived. While it would be overly optimistic to think the park would ever again see such a high number of hemlocks, Gubler is optimistic that the adelgid can be successfully countered and won’t wipe out the park’s remaining hemlock stands.

“I think bio-controls, predatory beetles, is our best bet,” he said.

Comments

You've obviously put a lot of time into this article, Kurt and the perspectives from throughout the NPS system paint a broad picture of a problem I am afraid we are powerless to stop. Here in the Smokies, many hundreds of thousands of dollars have been spent waging chemical warfare against this pestilence but it seems to be of little value. I was told by a biologist I met atop Mt. Rogers two years ago that all we can do is enjoy them while they are here. He insinuated that he has studied this blight for years in graduate school and the adelgid will eventually have its day and the Hemlock will go the way of the Chestnut giants.

I hope he is wrong, but a stroll through Albright Grove seems to suggest otherwise. Thanks for taking the time to go in depth.

Hope springs eternal, John. Even for the American Chestnut!

https://caldwelljournal.com/chestnut-restoration-may-be-happening/

I have to say I am more optimistic about the future of hemlock, especially in the Great Smokies. The chemical controls are very effective. Losses of hemlocks you see in the Smokies are due to the initial wave of mortality, which impacted the oldest trees the most and overwhelmed control efforts. The drought of 2007-08 impaired the tree's ability to uptake the systemic chemical but that was the last last wave of hemlock mortality. With biocontols documented as established and spreading the future is bright. Chemical controls cannot be relied on forever and the future is biocontrol and occassional cold temperature winter kill. Enjoy places like Cosby nature trail and Low Gap trail, which are virtually undamaged by HWA. Other places have impacts but the trees are holding their own now that the initial wave of mortality has passed.