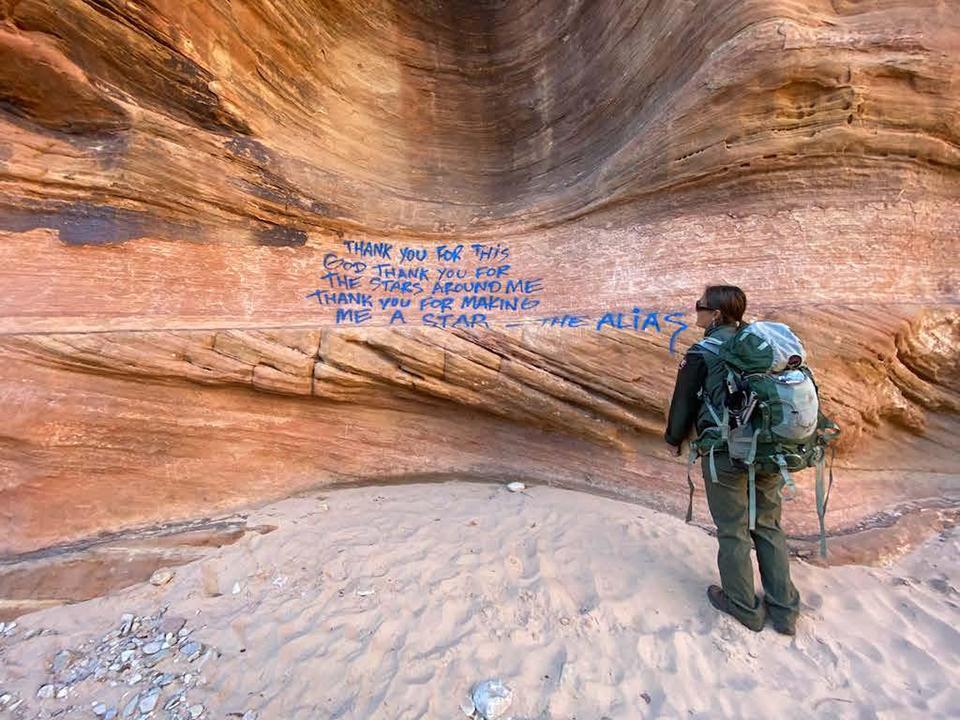

Blue paint graffiti in Zion National Park / National Park Service

Every time I read a Traveler article about more graffiti in the national parks, I get pretty damned angry. Didn’t the parents of these perpetrators teach them any better about respecting national parks and the laws within these park units? Have these perpetrators learned nothing at all about being a good steward of the land that’s left to them?

The National Park Service units are the few remaining parcels of land that are protected by law. This means chopping down a Joshua tree in Joshua Tree National Park or running an ATV over ecologically fragile ground on the Appalachian National Scenic Trail or chiseling a carving or painting acrylic on cross-bedded sandstone almost 200 million years old is illegal. This is noted on park signs, in visitor centers, in park newsletters, and on park websites.

Ever heard of the Leave No Trace Seven Principles?

And yet, here we are, with another story about vandalism in the parks.

But, much like photography, is the argument above subjective? Could modern graffiti in a national park be considered future historical info and art, as we today consider the ancient pictographs and petroglyphs carved into or painted onto canyon walls in Canyonlands National Park, and onto large boulders like Newspaper Rock in Petrified Forest National Park?

Newspaper Rock, Petrified Forest National Park / Rebecca Latson

I help the Traveler maintain its Instagram account @national_parks_traveler. I created a post about the most recent Traveler article regarding graffiti in Zion National Park. Among all the Instagram commenters condemning the act, there was one Instagrammer who asked why there was such a difference in how we perceive ancient graffiti (pictographs and petroglyphs) from current graffiti and anything else considered a modern oddity popping up in a national park or other protected land (that Instagrammer brought up the recent report of the 12-foot metal monolith erected out in the Utah desert and which has since been removed).

At first, I was annoyed at the question and the thought that this person would even ask something so ridiculous, but I ultimately realized others probably have the same question. What is the difference?

Pioneers and Native Americans traveled through parts of what are now national parks and national monuments and other protected lands, leaving their marks before moving onward. Some of those carvings and pictographs may have been actively used as informational sites, directional pointers, warnings, or to denote a holy site.

Or, they might just have been the doodles of a long-dead person tired of the journey, bored out of their mind and looking for something to keep them occupied. The markings, for whatever reason they were gouged/chiseled/painted onto rock and wood, help us learn about those ancient peoples that came before us.

The short answer to that Instagrammer’s question is that back then, there was no National Park Service and those lands did not enjoy the protected status they do now. Because of the establishment of the National Park Service and the mission this agency serves, modern graffiti and other wanton destruction of rock or wood or historic structures in these park units is illegal and considered vandalism.

The longer answer to that Instagrammer’s question is more complex and entirely my own opinion.

Way back before there was a John Muir or Stephen Mather or Theodore Roosevelt, people were concerned with just basic survival. I’m sure they saw and remarked upon the natural beauty of the landscapes over which they traveled, but more than likely, they viewed it all as more of a road to wherever their destination lay: a means to an end of their journey. They had no interest and no need to protect that through which they traveled since they were more concerned with just making it out alive. There was no telephone, no television, no radio, no internet. The carvings, etchings, and paintings they left on rock and wood were essentially “social media” messages to others following in their footsteps, hoofprints, and wagon wheel ruts. These messages claimed that they were there, they were alive, and if they had made it that far, then so could others.

Fast forward to the 21st century. We’ve got plenty of social media outlets now to tell others about how special we are and where we’ve been and where we’re going. That stuff will be chronicled somewhere in The Cloud and on the Web for future archaeologists to parse through (because even though we may delete things, they never really go away, do they?)

Hey, I don’t hate graffiti. I do think it’s a form of art. I’ve seen some beautiful street art – the term for graffiti when painted with permission or commission. I’ve run a number of searches on graffiti and where it’s legal. Among the online articles I pulled up is one interesting 2015 story in the online Medill Reports Chicago about artists making the graffiti leap from illegal to legal. And the key words are “permission,” and “legal.”

Call me a rule follower, but I don’t believe in trespassing, which is what this national park graffiti vandalism is: it’s the trespass of one (or more) for their own selfish purposes upon the natural landscape protected by laws set up for the purpose of preservation for current and future generations to enjoy.

Wildlands (and wildlife habitats) are shrinking due to climate change and human encroachment. These protected wildlands are all we have left, and even then, some of them have been reduced in size. With what we have learned thus far, the majority of us (hopefully) are understanding the value of the natural landscapes protected by the NPS. Most of us understand how ecologically precious (and fragile) these environments are. We want them to remain as they are, for ourselves and for future generations, to remind us of what the land all over the nation once looked like and the wildlife variety that roamed that land, before we farmed, concreted, and mined it to our specifications.

The more plugged in we become, the more we need these natural respites from “civilization.” We need to escape the sounds of the city and listen to the sounds of the peace and quiet. Time spent in a national park unit is good for our overall health. National parks spur our imagination and creativity just by looking at wildlife freely roaming the parks and magnificent landscapes unaltered by the hand of man (just ask any photographer).

We don’t need or want anybody to deface these panoramas protected by law. We don’t need or want acrylic paint on 180-million-year-old cross-bedded sandstone, or chiseled reminders on trees (living or dead in a park) that somebody loves somebody else, or that somebody and their dog were there. We need these protected natural places to remain as they are: protected, and unblemished.

Graffiti etched into a living tree, Olympic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Graffiti etched onto a redwood tree in Stout Grove, Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park, Redwood National and State Parks / Rebecca Latson

There are too many other permissible avenues for graffiti to manifest itself. It’s not necessary for someone to carve out chunks of rock and wood in our national parks just for the hell of it and to let others know they were there. Modern graffiti has no place in the national park units, and it behooves all of us to teach our children and others about respect for these parks and their biological, ecological, and psychological importance. It starts with parents teaching their children to love and respect the land, then continues via schools, visitor centers, virtual and in-person ranger- and volunteer-led events, and yes, even via social media.

So, there’s my long answer. It’s probably full of pitfalls and arguments I may not have noticed, but it tells you why I believe graffiti (ok, modern graffiti, if you want to get nitpicky about it) has no place in any of the national park units. Not only is it breaking national park laws, but it’s a form of trespass, and a selfish, willful deafness to the voices of the larger number of us who condemn the act of despoiling the environmental riches given to our stewardship for present and future generations.

Comments

"running an ATV over ecologically fragile ground"This quote from the article triggered a related question. Why are automobile, SUV and ATV ads on television seeming to glorify splashing through streams, tearing over sand dunes, and racingup hillsides so prevalent? We are constantly reminded to protect our environment for ourselves and our grandchildren, yet vehicle ads seem to advocate the opposite. This article is thought provoking and needs wider distribution. Thanks Ms. Latson

Well presented-- what is graffiti ? Before & after regulation & laws. Rebecca is right on all cosiderations-- will the underinformed read her mindset? No, but its a start. Life takes constant review as every day things change. I have photos of Casey Nockets painted drawings in Rocky Mountain National Park in 2014.

But those that continue to graffiti are not those that read articles such as these.