Editor's note: In the last part of his look at the history and preservation of America's Civil War battlefields, as captured in Pilgrim Places: Civil War Battlefields, Historic Preservation, and America’s First National Military Parks, 1863-1900, historian Richard West Sellars looks ahead to explains how the first military parks were created. (You can purchase the entire article, complete with footnotes and photographs, from Eastern National).

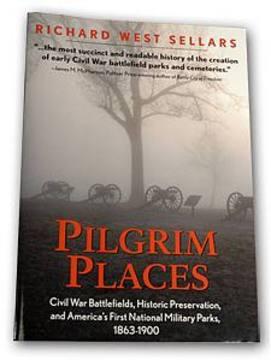

Pilgrim Places: Civil War Battlefields, Historic Preservation, and America’s First National Military Parks, 1863-1900

By Richard West Sellars

Part VII: Beyond the 19th Century

After Vicksburg’s establishment as a military park in 1899, it was not until 1917 that Congress authorized the next Civil War battlefield park at Kennesaw Mountain, northwest of Atlanta, where the Confederates stalled, if only for a while, the Union army’s southward march through Georgia. In the mid-1920s, other famous Civil War battlefields became military parks, including Petersburg and Fredericksburg, in Virginia.

And in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt transferred the military parks from the War Department’s administration to the National Park Service, which was already deeply involved in the preservation of historic places associated with early Native Americans, Hispanics, the American Revolution, and westward expansion. The Civil War military parks thus joined a growing system of preserved historic sites, along with a number of well-known, large natural areas, including Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and Great Smoky Mountains national parks.

Through the rest of the 20th century, numerous other military parks were added to this national system, including sites significant in the Union army’s extended siege of Richmond, Virginia; the battleground close by Bull Run and near Manassas, Virginia, where the Confederate army won important victories in 1861 and 1862; and Wilson’s Creek and Pea Ridge, sites of closely contested battles in the Trans-Mississippi West. Also, Civil War-era sites other than battlefields came into the system, such as the home of the great African American leader Frederick Douglass in the District of Columbia; Andersonville, the Confederate military prison in Georgia; and the Lincoln Home in Illinois.

At the Civil War battlefields, the stratigraphy of history has been rich, complex, and often controversial. Looking back through the decades, the preservation and public attention given the national military parks (and the huge number of other Civil War sites, both public and private) reflect a continuing ritual—a long rite of passage that began during the war and has remained strong into the 21st century. The nation and its people, Northerners and Southerners, black and white, and from academics to battle re-enactors, have contended with the memories and the meanings of the vast, tragic four-year struggle.

Compelled by the war and its times, each generation has commemorated—and celebrated—the battles and the war in a sequence of activities that forms an extended, multi-layered commemorative history founded on enduring remembrances that will reach far into the future.

Comments

Richard,

Quite enjoyable, and very informative body of work. I found it interesting how the different battlefields were saved in different time periods, especially in regard to Gettysburg.

I reside in Richmond, Va., where we are literaly surrounded by National Battlefield parks, as well as state and private Civil War parks. The South was indeed late getting into the game, but I suppose that can be attributed to the fact that the region was so decimated at the conclusion of the war, that there were no extra resources for such conservation. Virginia in particular was so war-ravaged that it took until nearly the turn of the century for the area to fully recover.

From the seat where I write this, I am within a couple of miles of Chickahominy Bluffs NBP, which recently received a much needed facelift. The entire swath of Maclellan's failed Peninsula campaign lies just beyond the swamp that is known as the Chickahominy River, and basically within the arc that I-295 creates East of Richmond. With so much history in your hometown, sometimes it's easy to overlook it with complacency. That's why the conservation of these areas is so important.

I would like to see you delve deeper into the Southern National Battlefields, The ones in the Richmond area in particular.

Thanks for a truly fascinating read!

dap