Editor's note: This updates the story to reflect that the Biden administration moved on January 15 to protect more than 300,000 acres of federal land in southwest Nevada desert from new mining claims for 20 years, and that the National Park Service has conveyed two easements for access to a gold deposit within Lake Clark National Park and Preserve.

As far as the Biden administration is concerned, a proposed Alaska mining road through a U.S. national park and adjacent federal land is kaput. Rejected. Case closed.

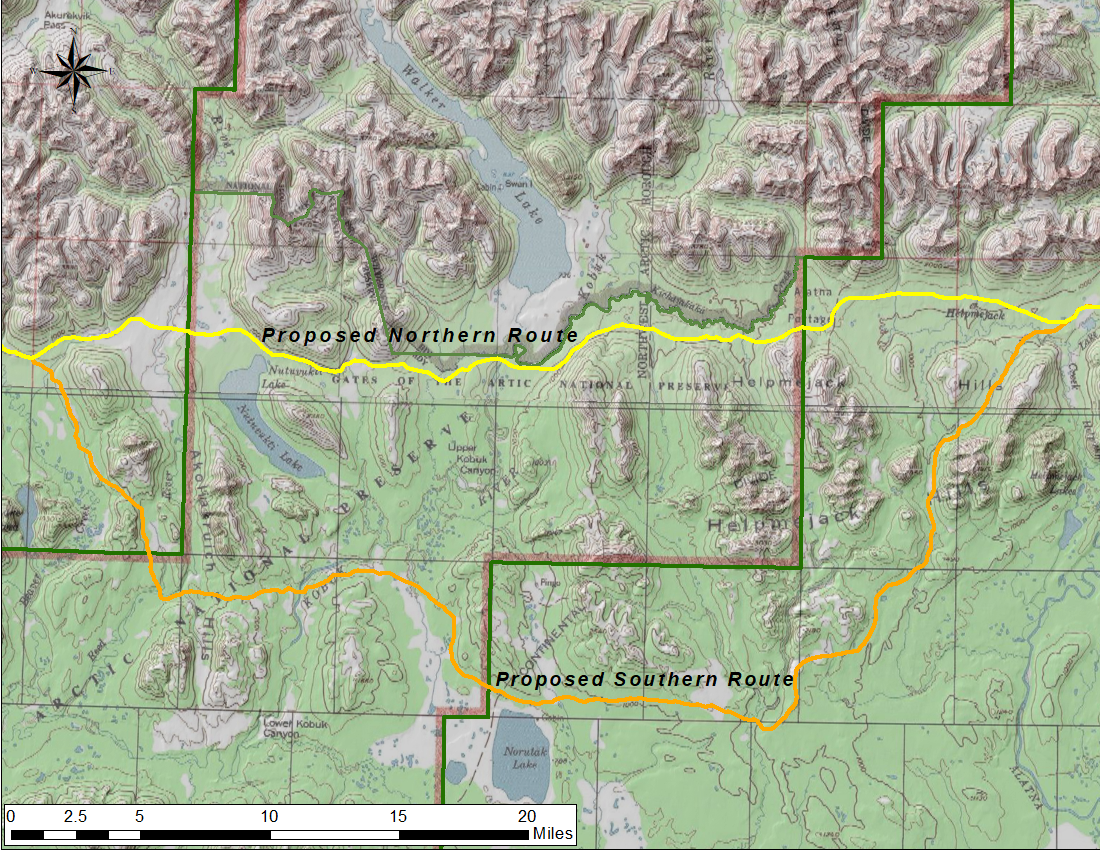

The Bureau of Land Management decreed it thus in a June “record of decision” that rejected a right-of-way across the BLM-managed section of the proposed 211-mile Ambler access road. By extension, that nixed the 20-mile stretch that would have crossed Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve in the wildlands of the Brooks Range. The road, meant to serve hoped-for copper and cobalt mining, would irreparably harm Alaska Native communities and wildlife, including an already-declining caribou herd, BLM concluded.

“These natural wonders deserve our protection,” President Biden said at the time.

But that’s not how mining advocates in Washington and Alaska see the outlook for building the truck route that would link the Dalton Highway with the mineral-rich Ambler Mining District to the west.

Despite BLM’s cold shoulder in June — the Interior Department told the Traveler in a statement that it was “a final action” — Alaska’s governor, congressional allies and mining interests continue pushing for the road, their optimism enhanced by a shift in the political landscape.

November’s transformative election brought new hope, assuring Donald Trump’s return to the White House and sweeping in a Republican Congress. Trilogy Metals, co-owner of Ambler Metals, the Canada-based joint venture for a copper mine at the end of the proposed road, saw its stock price soar in the weeks after the election, Alaska media reported.

“Things are definitely looking a lot better for us than they were about a week or two ago,” reports quoted Ambler Metals’ managing director, Kaleb Froehlich, saying in November at an Anchorage conference. “We do have sort of an opportunity window in Washington, D.C. starting in January.”

That optimism appears logical, given that the first Trump administration had greenlit the road. That action brought litigation by environmental groups and then the reversal by the Biden administration.

After the election, Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy asked Trump for a Day 1 executive order to get the project back on approval track.

“Alaska stands ready and is eager to work with you to repair this damage wrought by the previous administration,” Dunleavy wrote Trump, characterizing that damage as “foreclosing future energy and mineral development.”

Next Phase

Political and legal fights about mines, many involving impacts on national parks from mining activity outside their borders, were around long before the November election pointed a government smiley face toward the mining industry alongside the welcome mat offered by candidate Trump’s “Drill, baby, drill” promise for oil and gas development.

Now, both sides are girding for a new phase of the battle — anticipating a variety of salvos, from executive and congressional actions to litigation and community pressure.

“We do not believe that the Trump administration can legally push forward or reverse the record of decisions in short order,” said Alex Johnson, director for the National Parks Conservation Association’s Arctic and interior Alaska campaigns. “But that will not stop them from attempting to do so and requiring us to file additional litigation to try to stop those actions.”

The proposed Ambler Road corridor would cross about 20 miles of NPS lands, including a crossing of the Kobuk Wild River, which has its headwaters in Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve/NPS file

Aside from Trump’s inclinations as chief executive, the potential for congressional efforts to ease the way for the mining industry also has critics on edge. Just this past November, said Johnson, NPCA, with Alaska native tribal representatives and other organizations, ramped up lobbying in the face of an Ambler Road amendment that Sen. Dan Sullivan, R-Alaska, got into the massive annual National Defense Authorization Act. The Senate Armed Services Committee had accepted the plank to overturn the right-of-way rejection and get the approval process moving again. High-level congressional negotiations removed the plank before the Defense bill went to a floor vote, Johnson said.

“That is one of the biggest threats we're facing and that we're preparing for,” Johnson said, referring to potential congressional action on park-related issues. “It’s a very real threat in the next Congress, since we've already seen it in this one,” he said.

Not Just Alaska

Gates of the Arctic in Alaska is among numerous parks in regions as varied as the rocky deserts of the Southwest and the verdant Boundary Waters of Minnesota that face ongoing or prospective impacts from nearby mining activity.

- The National Park Service is sounding the alarm at California’s Death Valley National Park, where potential mining across the border in Nevada could affect park water resources and harm its ecosystems and wildlife.

- The Pinyon Plain Mine on U.S. Forest Service land southeast of Grand Canyon National Park began mining in December 2023, a few months after Biden designated a new national monument, the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni-Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. The designation prevents new mining claims in the monument, but the still-on-the-books Mining Law of 1872 allows existing claims, such as those held by Pinyon Plain, to remain. The Environmental Protection Agency says the mine could contaminate local and regional groundwater vital to the Havasupai Reservation, and conservationists fear it could impact springs and creeks crucial to Grand Canyon’s sensitive species and visitors alike. The Navajo nation has protested shipment of ore across its land. Arizona’s governor and attorney general have asked the U.S. Forest Service, which manages the land where the mine is within the new national monument, to conduct a new environmental assessment to update impacts from the mine. Its last environmental review was in 1986.

- Minnesota’s Rainy River watershed was protected by the Biden administration from new mineral leases, but that appears headed for a reversal by Trump. Trump’s first administration renewed two mine leases in the region after President Barack Obama denied them. Biden then cancelled them after he became president, and in 2023 he ordered withdrawal of 225,000 acres of federal lands from new mineral leasing.

Previewing the next step in the years-long political wrangling, Trump told a rally last summer that he’d reverse the freeze “in about 10 minutes” once elected, and “turn the Iron Range into a mineral powerhouse like never before.”

Mining could impair the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Grand Portage National Monument, Interior Department officials say, as well as Voyageurs National Park, which hosts loons, snapping turtles, and dozens of native fish species that rely on clean water. Officials cited potential damage to water quality, wildlife, cultural resources and recreation values, and raised concerns about tribal rights and adverse impacts from mining activities on historic tribal lands. In Congress, the House passed legislation last year to reopen the land to mineral leasing, but the bill didn’t clear the then-Democrat-controlled Senate. The bill sponsor, Rep. Pete Stauber, R-Minn., presumably would meet better odds if he tries again with his party controlling both chambers.

The Pinyon Plain mine is about 6-7 miles southeast of Grand Canyon National Park within the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument. It had a valid existing right to mine uranium before President Biden designated the monument in 2021/©Ecoflight

What’s Next?

U.S. Rep. Raul Grijalva of Arizona, a long-time ranking member on the House Natural Resources Committee who recently stepped down from that position, worries about the new political environment, especially in light of the 153-year-old mining law that allows anyone to stake a mining claim on most public lands. National parks are excluded, but not BLM or Forest Service lands around them.

“Between the President-elect’s affinity for industry CEOs and our severely outdated mining laws, I’m deeply concerned that the incoming Trump administration is going to unleash an even more toxic and dangerous mining free-for-all than we already have,” Grijalva told the Traveler. “Mining companies — many of which are foreign owned — already get to lock up much of our public lands, take what they want, and pollute our water and air, all while paying nothing in royalties to the American people. In many cases, mining happens right next to some of our most treasured public lands, like the Grand Canyon and Boundary Waters.”

Congressional counterparts allege, however, that anti-development forces use overly restrictive environmental reviews and laws to hamstring legitimate efforts to navigate processes that can turn a claim into a mine. There are concerns that environmental activists see as even more troubling than actions affecting single mine projects: the prospect that the second Trump administration, with the Republican Congress’s help, will water down both the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, important tools in challenging mining operations on public land, to the benefit of businesses.

Here They Go Again

And just as the Ambler access road ping-ponged from approval in Trump’s first term to rejection under Biden, it could whiplash again in the new Trump era, said John Leshy, former solicitor for the Interior Department in the Clinton administration.

“They could reverse it, but not simply. They’d have to go through a process,” including new environmental review and analysis. BLM under Trump’s Interior Department would need to present an interpretation different than the agency’s conclusion in April to deny the permit, and “be able to defend it as rational,” he said.

“And then it would be challenged by the conservation groups and the villages, and then it would end up in court.”

That’s essentially what happened when major environmental organizations sued in U.S. District Court to block the 2020 Ambler right-of-way that BLM OK’d under then-President Trump. BLM ended up going back to the drawing table after Trump left office to address acknowledged deficiencies in its previous analysis. This time the decision emphasized impacts on the abundance of crucial subsistence resources for villages and residents in Alaska wilderness that’s home to 66 Native communities.

The road would impair habitat and sever the migration route for the Western Arctic Caribou, disrupting the herd’s migration BLM said. Crossing the federally designated wild Kobuk River, which American Rivers last year dubbed one of America's most endangered rivers because of the mine road proposal, and multiple other major rivers and streams, the road could harm abundant sheefish and salmon fisheries that are important to both Native people and recreational anglers.

Many Alaska Native communities and organizations oppose the road. Denying the road permit was an “important step toward a future full of wild salmon, healthy people, and healthy lands and waters,” said Anaan’arar Sophie Swope, executive director of Mother Kuskokwim Tribal Coalition. “It seems definitely with the new administration, a lot of things are going to be at risk,” she told the Traveler.

Trump poses it differently. “We will maximize Alaska’s mining potential,” he promised in a November 8 video message to Alaska that Dunleavy posted online.

At the same time, the state-owned Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority, a principal backer of the project, recently authorized up to $750,000 for litigation to challenge Biden’s decision. AIDEA notes that the 1980 law creating Gates of the Arctic National Park specifically states the government “shall permit” such a road through the park. The route also traverses BLM, state, and Native corporation-owned land.

Possible Precedent

The road would be a crucial supply route that’s key to developing mineral extraction in a roadless region of northwest Alaska. Proponents, including Alaska’s congressional delegation and some Native Alaska groups, emphasize jobs and economic benefits to the region and state. Triology Metals’ Froelich has promised “safe and responsible domestic production of minerals that are critical for our national security and clean energy technologies.”

Critics fear approval could serve as a precedent for mining activity elsewhere in the pristine Brooks Range, which holds one of the world’s largest protected parkland areas, its expanse connecting Gates of the Arctic, Kobuk Valley National Park, and Noatak National Preserve.

“The real nightmare situation is that it would open the floodgates to all sorts of other speculation and then mining activity surrounding these parklands,” said the NPCA’s Johnson. “It's some of the last really, truly wild, roadless, large landscapes on Earth. So we're trying to keep it intact.”

More Park Easements

Planned easements to access a future gold mine in Lake Clark National Park and Preserve also have raised red flags for conservationists and local residents.

The Park Service announced Thursday, January 16, that it conveyed two easements to enable access to the site of a future gold mine in the Johnson Tract, owned by an Alaska Native corporation in Lake Clark National Park. The easements authorize “initial activities“ to plan for transportation of minerals and a phased process and analysis ahead of mine construction.

The easements are for a port and a transportation route to the Johnson Tract, located on the west side of Cook Inlet, about 125 miles southwest of Anchorage. The tract is owned by one of the state’s Alaska Native landholding corporations, Cook Inlet Region, Inc. Conservationists have raised questions about possible impacts on wildlife, including the park’s brown bears, and the critically endangered Cook Inlet beluga whales, a top-10 priority marine species designated by NOAA Fisheries’ for urgent recovery. The beluga inhabits Tuxedni Bay, where environmental groups say that noise and ship traffic from the proposed port could negatively impact its health and survival.

Beluga whales in Cook Inlet are at risk of mining impacts/NOAA

The beluga population declined by nearly 80 percent between 1979 and 2018, to an estimated 279 whales, according to NOAA. Surveys from 2022, indicate a mean of 331 whales, suggesting that the population may be stabilizing and perhaps increasing.

The Park Service was required to provide the Johnson Tract easements under terms of the 1976 Cook Inlet Land Exchange passed by Congress. The agency last year sought public comment for a “resource analysis.” Asked about the status, the Park Service public affairs office told the Traveler it had no “news to share” on the Johnson Tract.

Beyond Alaska

In the desert Southwest, water — a prized commodity — is a tension point amid an upswing in interest in exploring for lithium, an essential element for batteries used in electric vehicles, phones and other electronics. The Biden administration has encouraged exploration for such minerals as lithium, nickel, and cobalt to boost clean technologies in its quest to transition away from fossil fuels.

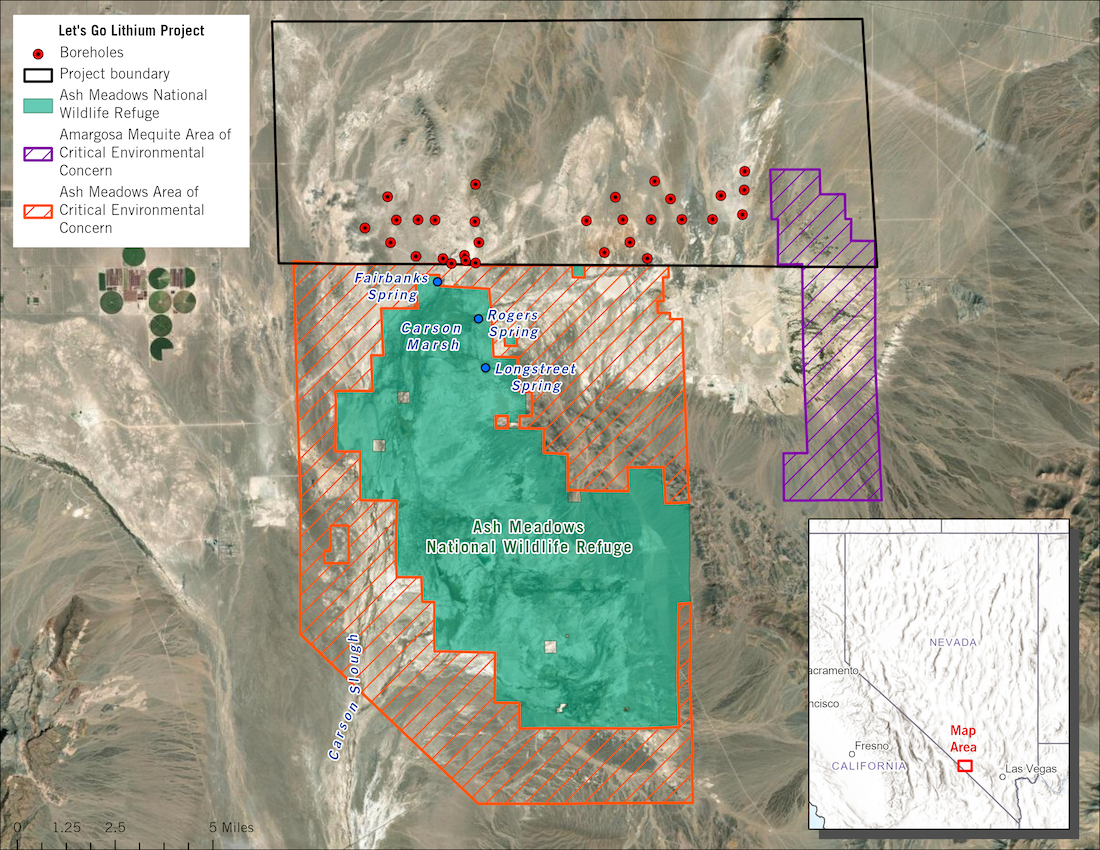

The problem for Nevada’s thirsty Amargosa Desert is that mining operations use water, some more than others, depending on the technology. Amargosa residents became alarmed in 2023 on learning that a Canadian company, Rover Metals, was set to launch exploratory drilling for lithium near Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, where spring-fed wetlands host the nation’s highest concentration of endemic species, according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

A diverse coalition — including Nevada’s U.S. senators and Democratic House members, the Timbisha Shoshone tribe, and officials from Nye County and local towns, along with conservation groups — petitioned the Interior Department to bar new mining claims on some 276,000 acres of BLM-managed land around Ash Meadows.

The Park Service and Fish and Wildlife Service backed the petition, and cautioned that mining-related groundwater pumping would impair water that’s vital to species including the endangered Devils Hole pupfish. The tiny pupfish is at high risk of extinction and exists solely in a deep Ash Meadows limestone cave, a detached unit of Death Valley National Park that lies in Nevada just across the California border.

A Canadian company wants to search for lithium deposits close to Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge when the BLM put a halt to the project in 2023/Center for Biological Diversity

Death Valley officials warned that the park itself would feel impacts because mining withdrawals in Amargosa Valley could deplete aquifers that, due to groundwater flow patterns, feed the park’s own wildlife habitat, as well as Ash Meadows.

“Death Valley NP is the driest place in North America, and this makes groundwater inflow from areas outside of the park extremely important,” the Park Service wrote in an August 20, 2024 letter to BLM.

In July 2023, after environmentalists sued and The Nature Conservancy provided a hydrology report on the ecosystem impacts, BLM said it had erred in not flagging Rover’s exploratory drilling notice because it had been unaware of the harm to Ash Meadows species. The agency reversed its decision and directed Rover to develop an operations plan and conduct more environmental studies.

“In the desert, water is everything, and especially in our national parks,” said Patrick Donnelly, the Center for Biological Diversity’s Great Basin director “Mines reduce water. They pump water. They will drain the aquifers.”

A flurry of new claim stakes appeared in and around the community of Amargosa Valley last spring. Most were tagged as belonging to Rover, according to Donnelly and Mason Voehl, executive director of the Amargosa Conservancy. They counted at least 400 new claims.

“We are extremely concerned about this dramatic rise in mining activity directly adjacent to Death Valley National Park,” said Voehl. “All we're saying is there are simply some places that just are too sensitive to do this, and surely there have to be other places. And we do support the need for a better domestic US supply chain as well.”

The Biden administration moved on January 15 to protect more than 300,000 acres of federal land in southwest Nevada desert from new mining claims for 20 years. The proposal includes acreage adjacent to biodiversity-rich Ash Meadows, home of the highly endangered Devils Hole pupfish.

In announcing the action, the Interior Department began a two-year pause on new mining claims while launching a 90-day public comment period and a review process for the full 20-year withdrawal of acreage from new mining activity. “The purpose of the proposed withdrawal is to protect the cultural, recreational, and biological resources of these lands,” the Bureau of Land Management said in a statement.

The Center for Biological Diversity hailed the action as “a historic day for Ash Meadows and the entire Amargosa River watershed.” Donnelly, added, “Ash Meadows is the crown jewel of the Mojave Desert and mining pollution doesn’t belong anywhere near this ecosystem.”

Utah Rush

New neighbors also are multiplying around Utah national parks, in the form of lithium claims being staked on nearby federal lands. The state has seen a “significant uptick” in claims, including around the river-carved buttes and dramatic rock landscapes, said Landon Newell, staff attorney for the Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance.

A company named A1 Lithium received a BLM permit in October to conduct exploratory drilling and sampling for lithium and bromine in two abandoned well bores that were left from the days when oil and gas drilling dotted the landscape. A1’s exploration is to occur along Route 313 that leads to the entrance of Canyonlands National Park and to Dead Horse Point State Park.

Newell’s group has filed an administrative challenge, contending BLM has not sufficiently weighed the project’s impact on wildlife and impairment of sweeping views that draw visitors to Canyonlands. Newell also calls on BLM to approach water issues more holistically, considering projects not in isolation but looking at potential cumulative water system pressures from claims that will conduct exploratory efforts or develop operating mines.

“This area is way too special to go about it on a piecemeal approach,” Newell said. “A project on a few acres may not seem too bad,” but bigger projects are bound to follow if enough lithium is found, he said.

“Yes, we need to transition to a cleaner energy economy but that doesn’t mean we have to sacrifice some of the most special places in our country to get there.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places