In Natchitoches, Louisiana, the Texas and Pacific Railway Depot will soon become a visitor center for Cane River Creole National Historical Park and tell stories of segregation and the local African American experience/Jennifer Bain

The gorgeous yellow brick train depot with an ugly past sits alone on Remembrance Way in Natchitoches waiting for the chance to tell its story. It’s a disturbing story of separate entrances, separate waiting rooms and separate washrooms. But it’s also an inspiring story of people fleeing the segregated South for better opportunities.

Built in 1927 in Italianate and Spanish Revival architectural styles, the Texas & Pacific Railway Depot handled passengers until 1969 and is one of the last surviving examples of a segregated building in Louisiana.

For nearly four decades, the community tried to preserve and rehabilitate the depot into a museum that tells the stories of local African Americans. In 2019, the city found the right steward and leased the depot to the National Park Service as the headquarters for Cane River Creole National Historical Park.

In a renovated waiting room once used by Black passengers at a train depot in Natchitoches, the word "Colored" is marked at the entrances. The NPS will reopen the depot as a visitor center for Cane River Creole National Historical Park. The ticket counter is on the left and behind it is a larger waiting room for white passengers/Jennifer Bain

Come fall, thanks to an extensive rehabilitation project, the depot is slated to reopen as the park’s first visitor center. In May, though, I got a sneak peek during a National Travel and Tourism Week ceremony that recognized locals — including a park ranger and a restaurant legend — who’ve helped make the community a welcoming place.

I noted the words “Colored” and “White” that have been repainted above the doorways. I acknowledged how much smaller the waiting room for Black passengers was. When I ducked into a staff washroom that the park’s chief of interpretation Barbara Justice said was once a “white ladies’ powder room,” I read about racism while washing my hands.

“The ability to use the same bathroom symbolized a kind of social equality between White and Black citizens, something that could not be tolerated by many people in the South,” that sign points out. “Safety, too, was an argument. Protecting White people from the non-existent threat of Black patrons was a commonly cited reason for keeping people separate. This was particularly highlighted in the case of bathrooms, where people were considered to be especially `vulnerable.’ Today, these bathrooms are open to all, but their foundation in unfortunate fears and unjust treatment remains an important part of this building’s history that should never be forgotten.”

At a train depot poised to become the Cane River Creole National Historical Park visitor center, Barbara Justice, the NPS chief of interpretation, stands by temporary signage about the local African American experience in Natchitoches Parish/Jennifer Bain

Throughout the depot, makeshift signage hints at how interpretation panels will soon read. Outside, a six-foot steel marker explains that this Louisiana Civil Rights Trail stop is “a symbol of the Great Migration when African Americans migrated from the rural agricultural communities of the South to industrial cities in the North and West” during the Jim Crow period and early Civil Rights movement.

Cane River Creole was established in November 1994 to preserve two of America’s most intact Creole cotton plantations.

It tells the stories of the workers (enslaved and tenant) and owners who lived on Oakland and Magnolia plantations for more than 200 years. It details an oppressive labor system founded on human slavery during the colonial era and later replaced by other legal mechanisms of oppression — including tenant farming, sharecropping and day labor — from Reconstruction through the 1970s.

“One of the things about the Park Service, we’ve done a really good job of telling stories up to 1865,” the new superintendent Kevin Downs told the crowd gathered for the tourism event. “Past 1865, there’s a lot of stories that we’ve really struggled to tell.” He urged everyone to return, hopefully in October, to learn about these stories when the depot reopens.

At Oakland Plantation in Cane River Creole National Historical Park, live oak trees shaded a main house built using enslaved labor/Jennifer Bain

Cane River Creole is one of two Reconstruction-era sites managed by the NPS in Louisiana, the other being Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve. The Reconstruction Era National Historic Network preserves “the places that gave African Americans hope and pride” after the Civil War.

If it seems strange that a park that’s pushing 40 doesn’t yet have a visitor center, there’s an explanation.

“What was different about this park is that there are two small plantations but they’re so complex and packed with resources that we didn’t want to build a new construction at the national historic landmark, because both are NHL sites so we didn’t want to disturb them and mess up anything,” anthropologist Dustin Fuqua, chief of resource management, told me.

“The last 25 years of this park has been preservation, keeping the buildings up, collecting the objects that were inside, and just getting stuff out so we could even do work in them. Also working on the mold.”

National Park Service anthropologist Dustin Fuqua shows off the Cane River Creole National Historical Park Curation Facility in Natchitoches on a private behind-the-scenes tour/Jennifer Bain

Just before Fuqua was honored at the tourism event, he led a behind-the-scenes tour of the park’s curation facility to show how artifacts are cleaned and stored.

Natchitoches, population 18,000 and pronounced Nack-A-Tish, is four hours northwest of New Orleans. Louisiana’s original French colony and the oldest city in the Louisiana Purchase was popularized in the 1989 hit Steel Magnolias. Cane River Creole — with two plantations 20 minutes apart in a rural area south of town — is another draw.

“Natchitoches is blessed to have a national park,” Arlene Gould, the retiring executive director of the Natchitoches Convention and Visitors Bureau, told the depot gathering. The park drew 11,701 visitors in 2023 as it rebuilds to pre-pandemic levels that were closer to 30,000.

I didn’t make it to Magnolia, but saw how the landscapes, outbuildings, furnishings and artifacts are being preserved at Oakland.

At Oakland Plantation, a store/gas station/post office started for sharecroppers and tenant farmers became a community hub until 1982. This is the view from the road/Jennifer Bain

The plantation was established in 1785 on a Spanish land grand and used enslaved African Americans to grow cash crops of tobacco and indigo (which was used for dye). Blacksmiths, carpenters and masons worked here, too.

After cotton gins were invented in 1793, the main crop became cotton. By the Civil War, nearly 150 enslaved people labored here and lived in one-room cabins that were converted to tenant housing after Emancipation. Descendants of enslaved workers remained as tenant farmers and sharecroppers until mechanization killed plantation agriculture in the 1960s.

The main house, a raised Creole cottage, was built in 1821 by enslaved workers and shaded by an avenue of live oak trees. Since there are already enough plantation homes representing the antebellum period, this one is historically furnished to the 1950s.

At Louisiana plantations like Oakland, pigeons were raised for food and to signify wealth and status. This one was closed when I visited at the end of the day in May/Jennifer Bain

I was fascinated by a two-storey pigeonnier, one of the most direct links between French and Louisiana architecture. Built as coops to raise pigeons for food, they became status symbols in France as only French landowners had the right to raise the birds. Louisiana’s version was less ornamental but still emphasized wealth.

Also fascinating is a store that was built for members of the formerly enslaved community who remained as sharecroppers and tenant farmers during Reconstruction. It evolved into a community hub offering food, drinks, gas and postal services until 1982.

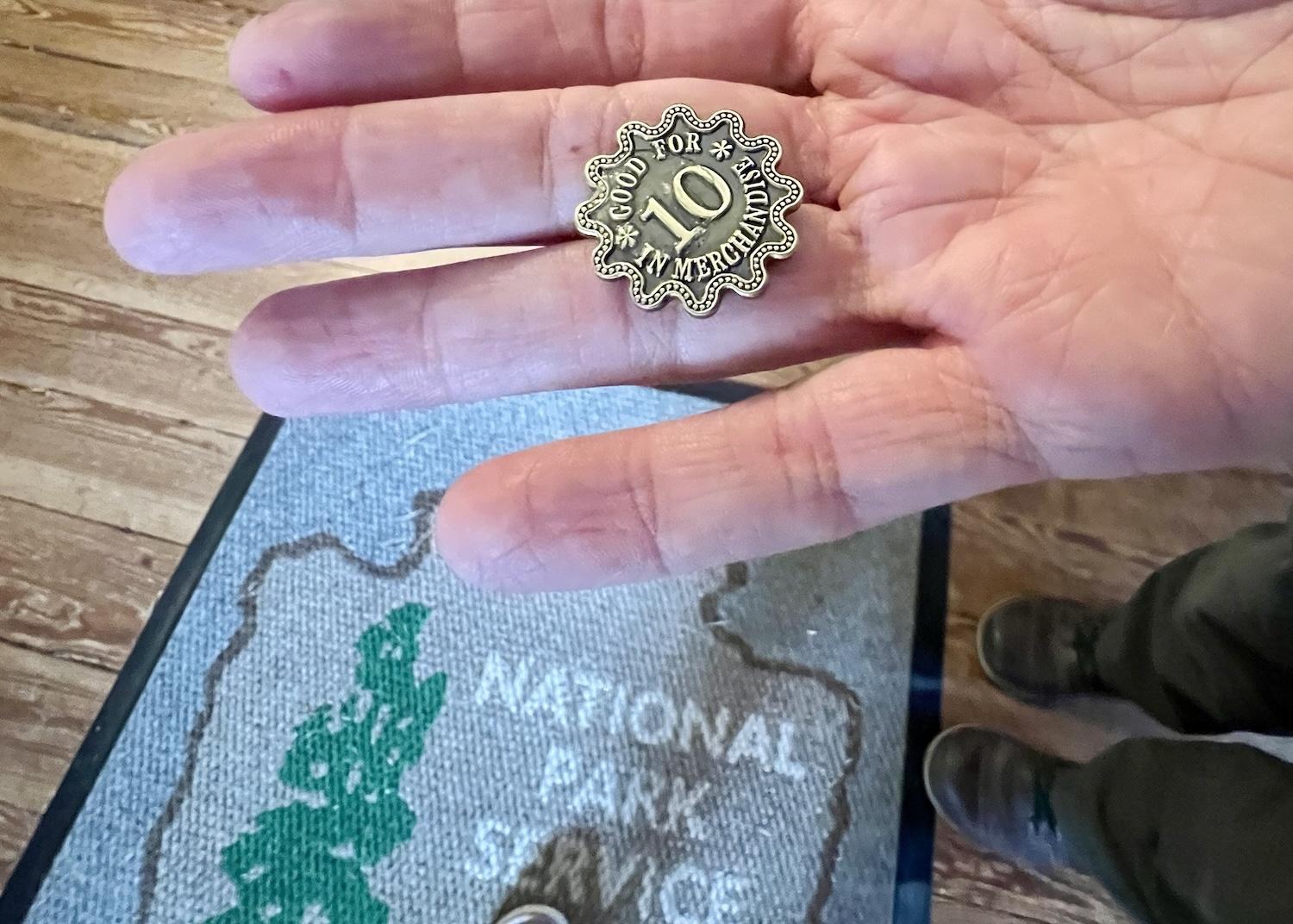

“This is the way it looked like in the mid 1960s but it opened in the early 1870s,” ranger Meghan Schill explained as she shared a replica token that’s sold in the park gift store. People were paid in plantation tokens that could only be spent at the plantation store. “Oakland only had paper money so we don’t have any on display of that and this one is from Magnolia, our other plantation. But people are more generally interested in the coins than the paper money.”

On Louisiana plantations, workers were given tokens instead of cash that could only be used at plantation stores. Ranger Meghan Schill shows a replica token from Magnolia Plantation that is sold by the NPS/Jennifer Bain

Cane River Creole preserves 62.36 acres of cultural landscape, 65 historic structures and about 600,000 inventoried artifacts. That number will eventually top one million, Fuqua predicts.

“The front-facing park of our park is the plantations,” he acknowledged on that curation facility tour. “This is the collections management part of things. (We’re) not doing a service by keeping it locked up in the dark and not letting anybody see it so the goal is let the public come here — but look at all the sensitive stuff.”

He battles insects, mold, bugs and pigeon poop. Objects are collected from the plantations, wrapped in plastic and put in a walk-in freezer before being vacuumed and shelved in the climate-controlled building not far from the depot.

At the Cane River Creole National Historical Park Curation Facility, artifacts from Oakland and Magnolia plantations (and other NPS sites) are frozen to eliminate bugs before storage/Jennifer Bain

“I don’t want to take those bug-ridden things and put them in here,” Fuqua said. “Some buildings were pigeonniers — pigeon towns — and there was two and a half feet of pigeon feces in these things so you’ve got to take all the safety precautions, including N90 and N100 respirator masks, Tyvek suits and sometimes even a forklift.”

While the NPS is tasked with preserving things “for perpetuity,” it can’t keep everything. Artifacts are rotated through Magnolia and Oakland and loaned to other NPS sites and museums.

Blacksmiths were revered within enslaved communities on Louisiana plantations and this well-worn anvil was deemed too precious to loan to the Smithsonian from Cane River Creole National Historical Park/Jennifer Bain

When the Smithsonian came calling in 2016 for southern cotton plantation artifacts for its National Museum African American History and Culture, public meetings were held. The consensus was to loan 32 items but withhold sensitive grave markers and a well-worn blacksmith anvil.

“When you go to the Smithsonian and you actually see a piece that came from your area, you are so proud that that came from Natchitoches,” said Gould, who joined the behind-the-scenes tour of the curation facility.

At the Cane River Creole National Historical Park Curation Facility, anthropologist Dustin Fuqua shows off vintage Cajun and Creole records from Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve/Jennifer Bain

Fuqua was in his elements showing off treasured artifacts.

To acknowledge the Native Americans who lived in this area first and were forced to move to Oklahoma, he showcased some of their river cane baskets. Important record albums from Jean Lafitte included some by Cléoma Breaux Falcon — known for the earliest Cajun recording — and others by Amédé Ardoin, who laid the groundwork for Creole and Cajun music and was beaten after using a White woman’s handkerchief during a concert.

“When the depot comes,” Fuqua promised, “things are going to be more forward facing, more public facing.” First there will be static exhibits, but as the funding rolls out there will eventually be “high-tech stuff.”

In what's soon to be a visitor center in Natchitoches for Cane River Creole National Historical Park, you can see a NPS lectern and evidence of this building's former life as a segregated train depot/Jennifer Bain

Back at the depot — a quick walk from my room in a 1940s bank that's now the Church Street Inn — I learned plenty just by eyeballing the draft signage about things baseball, the U.S. mail, music and food.

Baseball was a way of life in Natchitoches Parish from the 1930s to the 1960s. Plantations like Magnolia had teams made up of sharecroppers and tenant farmers that played after church on Sundays. One player, Nora Listach, made it to the Negro League, and his grandson Pat Listach made it to Major League Baseball.

Locals fought for civil rights. The train carried the U.S. mail “securely and privately” allowing people to voice their concerns about discrimination in letters mailed to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and federal agencies. "There was a postal box outside and we waited for the midnight train to post letters at the last minute so they didn't go through local hands," reads a comment from local resident Edward Ward.

What was once a segregated train depot in Natchitoches is now the headquarters for Cane River Creole National Historical Park and will soon be a visitor center/museum with a focus on local African American stories/Jennifer Bain

The morning that I visited the depot started with breakfast at Lasyone’s Meat Pie Restaurant.

I knew that the signature deep-fried pastry filled with beef, pork, onions, peppers and spices was a local specialty that reminded me of empanadas. But it wasn’t until arriving at the depot and watching retiring waitress Marilyn Demars get honored for 53 years of service that I learned that meat pies were popular on plantations and their recipes have been passed down for generations in the African American community.

There were cookies on offer at the depot event from what was once the ticket counter that served passengers from both races. But even when they were going to the same place and paid the same fare, these passengers stood in waiting rooms separated by a brick wall to buy their tickets. African Americans were forced to wait until customers on the White side were served.

As signage-in-progress quoting local resident Gwendolyn Antee details: "I remember there were Whites on one side, but we didn't really see them, I just knew they were over there."

In Natchitoches, everyone eats meat pies from the family-owned Lasyone's Meat Pie Restaurant. The dish was once served on plantations/Jennifer Bain

Cane River Creole works hard to maintain a relationship with the descendant community. Memorial illumination events remember and honor the people who were enslaved at Magnolia and Oakland. People are being invited to share their depot experiences and photographs.

The rehabilitated depot will, the Park Service promises, tell stories of "overcoming hardship from enslavement to abolition, from segregation to civil rights, no matter how difficult they may be so that future generations can learn from those stories.”

Leaving the depot that day in May, though, I smiled at the "Remembrance Way" sign. Last year, the park and the Cane River National Heritage Area co-sponsored a student essay contest to rename Depot Street to something that reflects and honors the area's rich Black heritage, history and culture. "A street name is powerful as it reflects who we are as a community and as a nation," Justice wrote in a news release.

Melodie Rice, an African American sixth grader, won $1,000 and will get to read her winning essay at the depot's grand opening.

The road leading to the Texas & Pacific Railway Depot in Natchitoches was renamed Remembrance Way in a 2023 "Name Depot Street" essay contest won by local elementary student Melodie Rice/Jennifer Bain

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places