Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This week's contribution is from Mike Stickney, Director of the Earthquake Studies Office at the Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology.

The landscape of the greater Yellowstone region has evolved gradually over millennia, punctuated by rare cataclysmic events such as volcanic eruptions, major earthquakes, and glacial outburst floods. The only such historical event occurred 65 years ago. The M7.3 Hebgen Lake earthquake took place at 11:37 p.m. local time on Monday, August 17, 1959, and unleashed the largest seismically triggered landslide in North America in recorded history.

Centered near the mouth of Madison Canyon west of Hebgen Lake, the Madison Slide extends a mile (1.6 kilometers) from head scarp to toe and is three-quarters of a mile (1.2 kilometers) wide. A section of the south canyon wall 1,300 feet (400 meters) high collapsed northward into the Madison River Canyon, sweeping 430 feet (131 meters) up the north canyon wall in places and creating a dam 220 feet (67 meters) high across the Madison River, behind which Earthquake Lake immediately began filling. The volume of the slide mass is estimated at 37 to 43 million cubic yards (28 to 33 million cubic meters) and covers 130 acres (0.5 square kilometers).

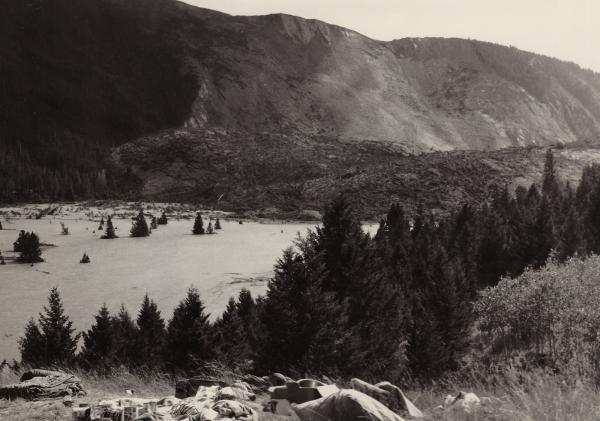

View of the Madison Slide on August 21, 1959, with rapidly filling Earthquake Lake. Rock Creek Campground was near the flooded trees. Camping gear was left behind by survivors who sought high ground following the slide/Professor William B. Hall, Montana School of Mines Geology Department.

A thick layer of Precambrian dolomite dips steeply northward along the base of the south canyon wall. This hard layer apparently formed a buttress that bolstered the deeply weathered and weak schist and gneiss of the slopes above. The strong shaking of the earthquake caused the dolomite buttress to fail, and the entire canyon wall slid. The slide mass maintained its stratigraphic order such that the dolomite forms a prominent tan-colored band along the leading edge of the slide, and the dark gray schist and gneiss followed behind. The toppled trees and topsoil of the north canyon wall came to rest on top of the slide mass, demonstrating a lack of churning and mixing as the slide mass moved.

According to eyewitnesses, the Madison Slide occurred from just a few seconds to perhaps half a minute after the strongest shaking of the Hebgen Lake earthquake had subsided. Tragically, the eastern (upstream) edge of the Madison Slide buried the overflow camping area just below the U.S. Forest Service’s Rock Creek Campground. Twenty-six people died there, including 19 whose bodies were never recovered and are presumed entombed in the slide mass.

A wave of muddy water accompanied the slide on the upstream edge, carrying trees, driftwood, and small rocks up to 100 feet (30 meters) above the river on the north canyon wall. The violent wave and the accompanying hurricane-force air blast that was displaced by the slide mass accounted for many of the casualties and destruction of vehicles and trailers in the Rock Creek campground.

By 6:30 a.m. the following morning, the waters in the newly forming Earthquake Lake had covered all the cars and trailers in Rock Creek Campground and was at least 20 feet (6 meters) deep. About 250 survivors assembled on Refuge Point, the highest ground between Madison Slide and Hebgen Dam. They were effectively trapped in the area because the earthquake also damaged the road in the upstream direction, so there was no way out of the Madison River Canyon. The most seriously injured were evacuated by Air Force helicopters around midday, and by late afternoon, a rough road bulldozed around the road-cutting landslides along Hebgen Lake, upstream of the Madison landslide, allowed the remaining survivors to escape. Twenty-five people with serious injuries were treated at hospitals in Bozeman, Ennis, Butte, and Sheridan, MT.

Hebgen Lake fault scarp in 1959/USGS, J. R. Stacy.

The U.S. Forest Service maintains a number of geological sites in the Hebgen Lake area, including a visitor center built on the Madison Slide and interpretive signs noting where survivors gathered on the night of the earthquake and the scarp formed during the earthquake itself.

Next week, we’ll continue the story of the Madison Slide with a look at the dangers the slide posed once it blocked the Madison River, and how engineers worked to stabilize the slide and mitigate those hazards.

Comments

Several houses and cabins were taken off their foundations by water from the Sieche that rolled back and forth and topped the dam upstream from the campground. One woman was tossed from her bed into water in her bedroom. She grabbed her dog's tail and he pulled her to shore. When rescuers reached her, they asked if there was anything inside her floating house that she wanted them to retrieve. She said the only thing really important was her false teeth that she had left beside the bathroom sink. When rescurers reached the cabin by boat, they found the false teeth right where she had left them.

The Forest Service displays up and down the canyon now and the visitor center on top of the slide are fascinating places to visit. A trip out there makes a great side feature to a visit to Yellowstone.