For 150 years, Yellowstone National Park has built a deep history of scenic delights, environmental preservation, and conservation, and yet it's a history that's given relatively short shrift to the Native cultures that long traversed and utilized the landscape known today as the world's first national park. That oversight is slowly being corrected in Yellowstone and in many other units of the National Park System where Native voices are expanding the interpretation and understanding of what these places mean and represent.

It's a process, formalized by the Biden administration under the Tribal Homelands Initiative signed last November, not without controversy.

“We don’t celebrate that this is the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone National Park. For us, it’s the anniversary of the date our land was stolen and thousands of years of peaceful use cut off,” said Francesca Pine-Rodriguez, a Crow tribal member who is executive director of Mountain Time Arts, a Bozeman, Montana-based nonprofit actively engaged in tribal projects within the national park. “Tribes were kicked out of a traditional economic epicenter and hunting ground when the park was created.”

According to Pine-Rodriguez, multiple tribes used Yellowstone's unique landscape and geothermal features as places of spiritual importance, healing, food gathering, hunting and trade. Tribes interacted peacefully, she said, and often learned from each other.

Those story lines are not always reflected in the National Park System, however.

Exploring Cultural History

America celebrates its national parks with grand entrance markers, often citing the date the park was authorized by Congress or the national monument formed by presidential order. That simple date places the landscape into the fabric of United States history, not cultural history that dates back millennia. In recent years, though, the National Park Service has strived to better tell the story of the parks by incorporating the views of those who came before Anglo-Americans claimed the land. Through associations and partnerships developing between the National Park Service and Indigenous peoples, new voices are interpreting the story of the lands the parks occupy.

At Yellowstone, the ancestral people using the landscape are seen as 27 tribes today, each of which has a perspective of how the park is trying to bring to the forefront its visitor messages, according to Yellowstone Superintendent Cam Sholly. The park works with all its associated tribes.

“We've come a long way in the last couple of decades in how we conduct tribal relations in the Park Service. I talked to a lot of tribes over the past 18 months,” said Sholly. “It’s why we opened the Tribal Heritage Center at Old Faithful."

But not everyone agrees there's a need for such emphasis, and fear the Interior Department under Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, is open to transferring park lands to tribes. While Interior hasn't hinted at such a move, the secretary has pointed to the value of strengthening engagement with tribes when it comes to management of public lands.

The Tribal Heritage Center at Yellowstone National Park/Eric Jay Toll

“From growing crops and taming wildfires to managing drought and famine, our ancestors have spent millennia using nature-based approaches to coexist among our lands, waters, wildlife, and their habitats," she said when the Tribal Homelands Initiative was signed. "As tribal communities continue to face the effects of climate change, this knowledge – which has been passed down since time immemorial – will benefit the Department’s efforts to bolster community resilience and protect Indigenous communities. By acknowledging and treating tribes as partners in co-stewardship of our lands and waters, we will undoubtedly strengthen our federal land and resources management.”

Although tribal representatives firmly believe ancestors were cut off from their traditional area use through creation of national parks, there is controversy about the Indigenous use of the Yellowstone area in 1872 when it was established as a national park. Richard Grant, writing The Lost History of Yellowstone in the January 2021 Smithsonian Magazine, echoes Pine-Rodriguez’s view of tribal removal from the land and went so far as to call for national parks to be handed over to tribes.

Grant's article drew a lengthy rebuttal from Yellowstone scholar George Wuerthner and former National Park Service Archivist Lee Whittlesey, who took issue with Grant’s heavy reliance on the cultural occupation theories of archaeologist Doug MacDonald. Their thesis is the one small tribe still living in Yellowstone at the time of park authorization was permitted to remain, while other tribes had long since abandoned the area. Their rebuttal, Are Native Americans Lost From Yellowstone? appeared in the National Parks Traveler in February 2021.

The National Park Service has stayed out of the controversy while focusing on creating associations and sometimes partnerships with tribes native to areas today holding national parks. Speaking in March 2022 to an inter-tribal gathering of the Tsaayu en’sikite (Eastern Shoshone) and Wouukohei (Northern Arapaho) people, Sholly acknowledged that early on the Park Service made mistakes.

“I think there is a lot of room for improvement moving forward with how we transcend beyond [the minimum]. We're obviously always going to, and have an obligation to, do formal government-to-government consultation,” he said, speaking with the National Parks Traveler earlier this month. “But what I found very valuable going into this 150[th anniversary is that] we've made a very cognizant effort to focus the anniversary on not just the commemoration of a national park, but to also use it as a point, a time to reflect more formally that American Indian tribes have been on this landscape for well over 10,000 years.”

Sholly agrees that the future for national parks in the American West is a broader recognition these lands did not begin with Congress setting boundaries on maps.

Tribal Ties

“Many tribes claim heritage on this land,” said Pine-Rodriguez, referring stories handed down through generations. “It was a peaceful gathering place where tribes traded, exchanged and celebrated.”

She stressed that the tribes recognize the superintendent is welcoming an Indigenous presence in the park. Her organization, Mountain Time Arts, hosted Yellowstone Revealed over seven days in late August. The Reveal revolved around a series of place-based projects within the park by an inter-tribal group of Indigenous artists and scholars. After the event concludes, some features, including teepees, will remain at open park entrances.

As the world’s first national park, the change in language about Yellowstone’s history is cited by both Sholly and Pine-Rodriguez as an important step forward.

“Our focus is on Yellowstone before its founding. I don't want to make it sound like there hasn't been good work with tribes done, but I do feel like we can do better,” said Sholly. “I think that what I found very successful is not only ensuring that we're adhering to our government responsibilities, but also collaborating with multiple tribes on ideas and different ways of doing things, moving, moving forward.”

Pine-Rodriguez says that in addition to the Tribal Heritage Center at Old Faithful, Mountain Time Arts is working with the park for permanent installations at entrances and throughout the park.

“I think that we have got a good start on getting tribes back on to the Yellowstone landscape and engaging them more,” said Sholly. “All the different tribes, they all have a connection to Yellowstone; 27 affiliated tribes. I think the job of looking at where we can collaborate and have events and find areas where we can involve multiple tribes. We've done a lot of work with individual tribes about what their needs are and their desires are.”

Canyon De Chelly, Chinle, Arizona, has indigenous settlements dating back more than 1,000 years before it was established as a national monument. Cave Ruins is one of more than 20 villages set next to canyon walls or built into wall alcoves above the canyon floor.

Some other national parks and monuments are increasing the conversations and interaction with associated tribes, but shared operations with tribes is part of Canyon de Chelly National Monument, Pipe Spring National Monument, Fredonia, both in Arizona, and Grand Portage National Monument in Minnesota.

At the Arizona monuments, tribal governments are partners in how the parks tell the stories, and in some operations. At Canyon de Chelly, the Navajo Nation Parks Department operates the national monument’s campground. In addition, NPS says that it assists the tribe with managing tour guides and access into the canyon itself, but that the Navajo manage the canyon.

It's a different situation at Pipe Spring.

“We share facilities, headquarters, and stories,” said Amanda McCutcheon, the superintendent. “We do our best, but many times, we defer to the (Kaibab Band of Paiute Indians). As much as possible, we will follow their laws and use the tribal resources for programmatic assistance.”

Pipe Spring, a site with its American history dating from an 1871 fort and settlement, is the site of an important water source and trade route used by animals and Indigenous people for thousands of years before there were any Anglo claims on the land. The National Park Service in-holding is surrounded by Paiute reservation lands. The tribe and the national monument share the same building for tribal government and the Pipe Spring Visitor Center.

“Pipe Spring was originally for the fort and (Mormon) settlement,” McCutcheon said. “Our mission is preservation, and we are being more inclusive with the story of the spring.”

There is still a long way to go to tell both stories, she added. The area was traversed and used by many different tribes. Ancestors of the Paiute and other tribes of the Pipe Valley and Kaibab Plateau in what is today the northern Arizona strip and southern Utah were drawn to the area by the water that percolates through sandstone cliffs. Ancestors of the Paiute farmed the area around the spring for more than 1,000 years.

“We’re surrounded by tribal lands,” McCutcheon said. “But we are just now increasing the programs and interpretations to be more culturally diverse. There’s always room for improvement.”

At Grand Portage, the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewain has handled maintenance of the national monument under an agreement signed in 1999, one that is the oldest in the country between a tribe and the National Park Service.

Hawai’i Volcanoes National Park has taken more active steps implementing the recommendation of Indigenous people. It has renamed sites and updated visitor information to reflect Indigenous stories and culture as recommended through consultation with Indigenous cultures.

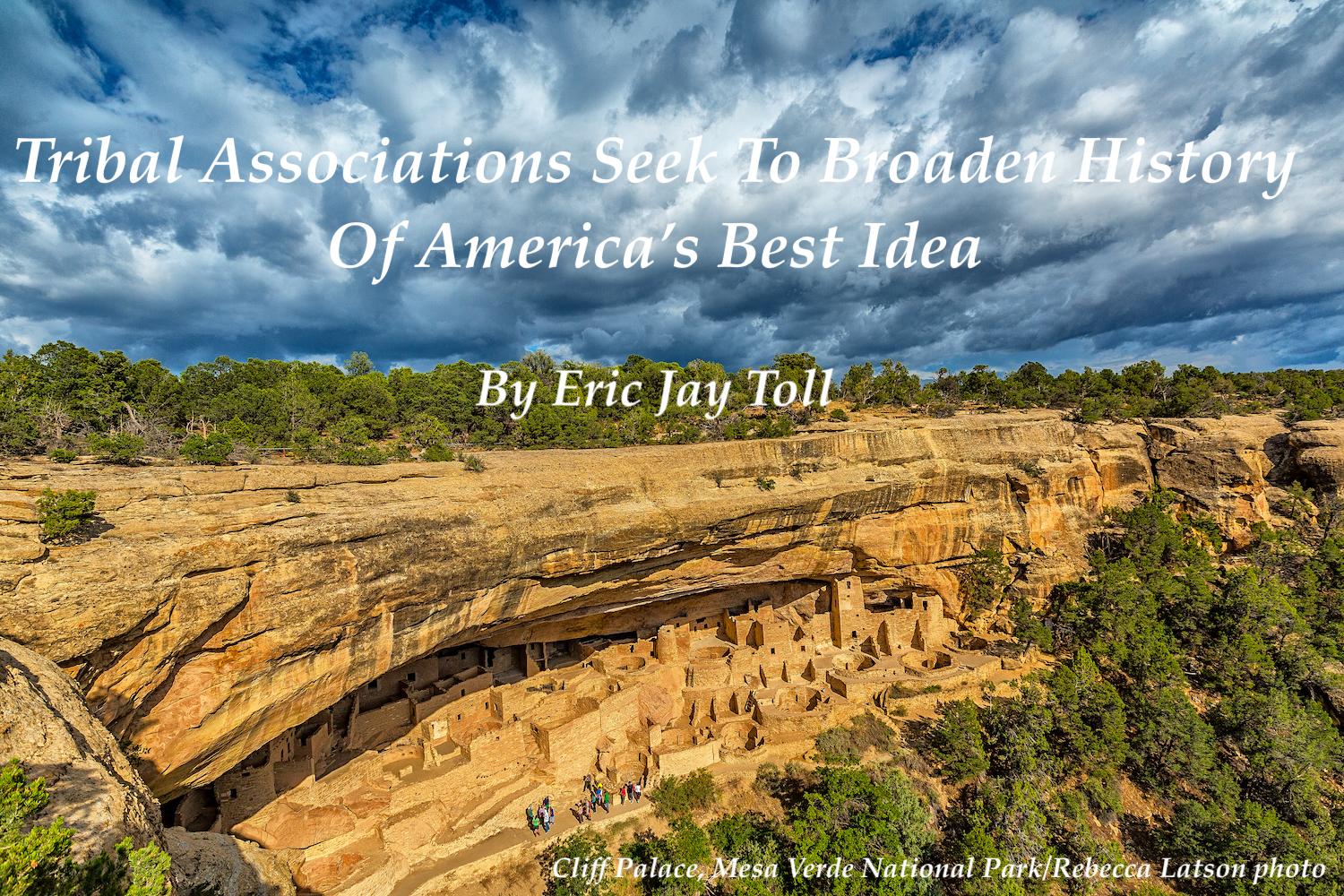

At Mesa Verde National Park, Chief of Interpretation Kristy Sholly [no relation to Cam Sholly] is spearheading a role to completely change the language of the park’s museum.

“We are empowering the Indigenous story in the [Mesa Verde] landscape,” she said. “This year we are adding a tribal engagement coordinator to our staff.”

Mesa Verde’s biggest partnership with the Utes and Pueblos is changing the park’s story in the museum. The historic 1920s building is redesigned to accommodate the shift from archaeology to ancestral history. The effort started in 2020 at an inter-tribal gathering and will be completed in 2026. Temporary exhibits should begin appearing this coming fall and winter.

“We started the design this year,” said Sholly. “It’s led by a tribal-pueblo group of eight. We’re privileged to be working with them, and we’ve heard what they’re saying.”

For most of the park’s history, its emphasis was the viewpoint of the archaeologists who excavated the site.

“This is a multi-tribal collaboration that determines a new future for the park and tribal story,” said Theresa Pasqual, a member of the park-tribal-Pueblo committee, an independent consultant and executive director of the Acoma (Pueblo) Historic Preservation Office. “It’s a great opportunity. I think the park is open to these kinds of discussions.”

Pasqual said that the effort requires adequate funding from the Park Service and working with the park to change the infrastructure necessary for the new exhibits. She sees the effort as more than just revising how Mesa Verde tells its story.

“This is an opportunity that really serves as an example of how a park, or any agency, can reflect the change in narration,” she said. “It’s a model of taking the story back that can be used at other parks.”

Although they’ve never spoken to each other, Pine-Rodriguez has the same mission for the association with Yellowstone.

“Correcting the Yellowstone National Park narrative with tribal engagement is more important than events,” she said, referring to the tribal view that the story has been too focused on the park’s history from its formation and the archaeology. “We see this program as a model that we can go to other groups and say, ‘this is how we did it.’”

At Yellowstone, Sholly acknowledged the park did not get it right for the first 150 years.

“In fact, we got a lot of things wrong. It’s easy to talk, hard to get organized and started. Momentum from the many tribes is important for the next 150 years at Yellowstone,” he said. “We do the best job we can, but no one can tell the tribal stories like the tribes. And so we've been very excited to have visitors this year being able to engage tribal members directly. I think we've also looked at the 150(th anniversary) as a starting point, not as like, ‘hey, we're just going to do it this year.’ Our plan is to continue to carry on. The (new) tribal center in future years will have great support from Yellowstone Forever and the National Park Foundation helping to fund a lot of these initiatives well.”

The momentum may be building to change the language of other national parks as well.

Comments

Tribes interacted peacefully...

Yeah, let's be realistic and not rewrite history in the other direction.

Mesa Verde:

There is little archeological evidence that today's Utes and today's Pueblos had any ties to the inhabitants of MV.

While being more inclusive storytellers is laudable, let's not pretend that there were ties b/t today's NAs and the ancients, when the evidence is just not there.

Whenever these efforts arise, it's important to note that the NA's sense of land "ownership" was and largely is not, the same as the Europeans'.

To try to apply today's language and legalisms to yesterday's interactions is a dangerous effort.

Don't often agree with you AJ but you are on point here. Same thing at Rushmore where the Lakota/Sioux that everyone feels were so wronged actually only occupied the Black Hills for about 100 years having done to the Cheyenne what was done to them And the Cheyenne themselves were preceded by the kiowa, pawnee and crow over a period of about 200 years with savage wars in the interim.

I've visted Mesa Verde NP twice. The road briefly traverses the Ute Mtn reservation. Where it does, there is a run-down shack (now covered with grafitti) that apparently was used by the Utes to promote their story and their reservation.

MV now employs Utes and Pueblos to conduct various ceremonies for tourists visiting MV, claiming that they are, "Pueblos and Tribes with connections to Mesa Verde." Sorry, there's NO historical or archeological evidence to support this claim.

I do find it worthwhile for neighboring NAs or interested NAs to present their views and their cultural ceremonies within our national parks, REGARDLESS of a substantiated connection to the park. Why not just enjoy the cultural exchange without making up the history?

I'm not sure where you're getting your information, A. Johnson, but this is entirely false. The Pueblo people are the direct descendants of the Ancestral Pueblo people. Please check your facts before you make misinformed comments. Also, the park used to be Ute land and was taken by the government via coercive land grabs.

Wishful thinking is not scholarship.

Fact: The MV region was largely abandoned by 1400. There is no archelogical evidence of habitation at MV after that date. While it is possible that there was intermittent visitation (hunting?) to the area after 1400, there is no evidence of anyone living there after that date.

Thus, it would be impossible for Europeans to have taken anything from anyone when there was no one to take it from. While it is confusing to speak of Ancient Puebloans and today's Puebloans, there is no known archeological, biological/genetic, or historical connection between the two (at this time; the future may bring new evidence of course).

Utes: The Utes were not originally from the MV region; they were moved from western CO &eastern UT to what is today's Ute Mtn Reservation. So in that sense, the Utes on Ute Mtn reservation are trespassers.

These facts are wdiely available, if and when one chooses to evolve beyond feelings.

Are these so-called indigenous peoples "Americans"? I read the entire article and I did not see the word "American" to describe them. Are they Americans?

Happily, I did not see "DEI" creeping into the "conversation," but it's all there. You see, it's all about the "engagement."

Why does America insist on sewing the seeds of internal discord?

America needs to stop the self-destrution now. Just say "no."