Giant Sequoias Are No Stranger To Fire

By George Durkee

Walking among the Giant Sequoia forests of the west slope of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, visitors are struck by the peace and sense of profound age surrounding us. Many of these trees live to over 3,000 years old – the so-called Monarchs – and have survived extensive droughts, fire, the Little Ice Age, floods, and now, the greatest potential threat to their continued existence, modern humans.

There is now a fire burning on the slopes below one of the largest groves of Giant Sequoia at Giant Forest in Sequoia National Park. Many press reports are understandably concerned that this fire – and others – can wipe out these iconic trees as fire spreads through the groves. Using sometimes overheated prose, they describe fire as possibly devouring the groves. Unquestionably, fires are often dangerous and even tragic but it is important that, in this new fire regime, we begin to put all fires in perspective and use them more wisely

In the sequoia groves of our national parks (Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon) though, there is hope that the long-time fuel treatments of the Giant Forest Groves will prevent any significant mortality of large trees, should this or future fires get that far.

The naturalist John Muir watched a fire burn up these same brushy slopes and into these very same groves in 1893:

In the forest between the Middle and East forks of the Kaweah, I met a great fire … . It came racing up the steep chaparral-covered slopes of the East Fork cañón with passionate enthusiasm in a broad cataract of flames, now bending down low to feed on the green bushes, devouring acres of them at a breath, now towering high in the air as if looking abroad to choose a way, then stooping to feed again, … . But as soon as the deep forest was reached the ungovernable flood became calm like a torrent entering a lake, creeping and spreading beneath the trees where the ground was level or sloped gently, slowly nibbling the cake of compressed needles and scales with flames an inch high, rising here and there to a foot or two on dry twigs and clumps of small bushes and brome grass. Only at considerable intervals were fierce bonfires lighted, where heavy branches broken off by snow had accumulated, or around some venerable giant whose head had been stricken off by lightning.

This is a description of what fire often used to look like – not only in Giant Sequoia groves, but in much of our mixed conifer forests of the Sierra. When Muir wrote these words, fire was still an integral part of the Sierra ecosystem. Fires were ignited either by lightning or through extensive burning by Native Americans.

Giant Sequoias, in fact, are a classic example of a tree and forest environment adapted to fire. The bark of the Sequoia is fibrous and can be up to 2 feet thick. It is adapted to withstand the heat of immediate fire. Muir described “bonfires” of heavy branches around the base of the trees, though most all of the ancient trees have large fire scars at their base.

The full life cycle of sequoias, like much of the vegetation of the Sierra and California, is dependent on fires sweeping through occasionally. It’s the heat of the fire that opens the cones and so allowing the seeds to spread. Equally important, sequoia seeds need bare earth to sprout in. The fire opens the cones and provides the bare earth for new seedlings. Other trees and shrubs in the West have similar needs and adaptations to fire to reproduce and thrive.

Indigenous peoples, of course, knew this quite well. For thousands of years they probably burned extensively in the lower elevations of the Sierra to maintain an environment that provided food for them. Acorns, for instance, were a staple when pounded, boiling water run over it to leach the tannins, and served as a mush. To maintain the oaks they depended on, Native Americans would burn off the underbrush and young conifers. The latter, if allowed to dominate, would shade out and kill the oaks. In addition to favoring an ecosystem dominated by oaks and some conifers, fire maintained an open understory with extensive shrubs, grassland, and browse for deer and other animals.

A Landscape Without Fire

A landscape without fire is exactly where we are today. Everywhere in the Sierra, mixed conifer are not only dominant, but are crowded in dense, even impenetrable, thickets that, when fire gets into them under the super dry and windy conditions we now increasingly face with climate change, explode into catastrophic fires almost never seen in California or the Western forests.

The trapper Joseph Walker was among the first Euro-American explorers to cross the Sierra in 1832. Although it’s long been thought Walker “discovered” Yosemite, it was much more likely he came down the western slope along the route of today’s Highway 4, well north of Yosemite, and passed the Calaveras Grove of Giant Sequoias. The trappers described a landscape of large timber and abundant game that they easily travelled through on their horses.

“In the last two days travelling, we have found some trees of the Red-wood species, incredibly large - some of which would measure from 16 to 18 fathoms round the trunk at the height of a man's head from the ground.”

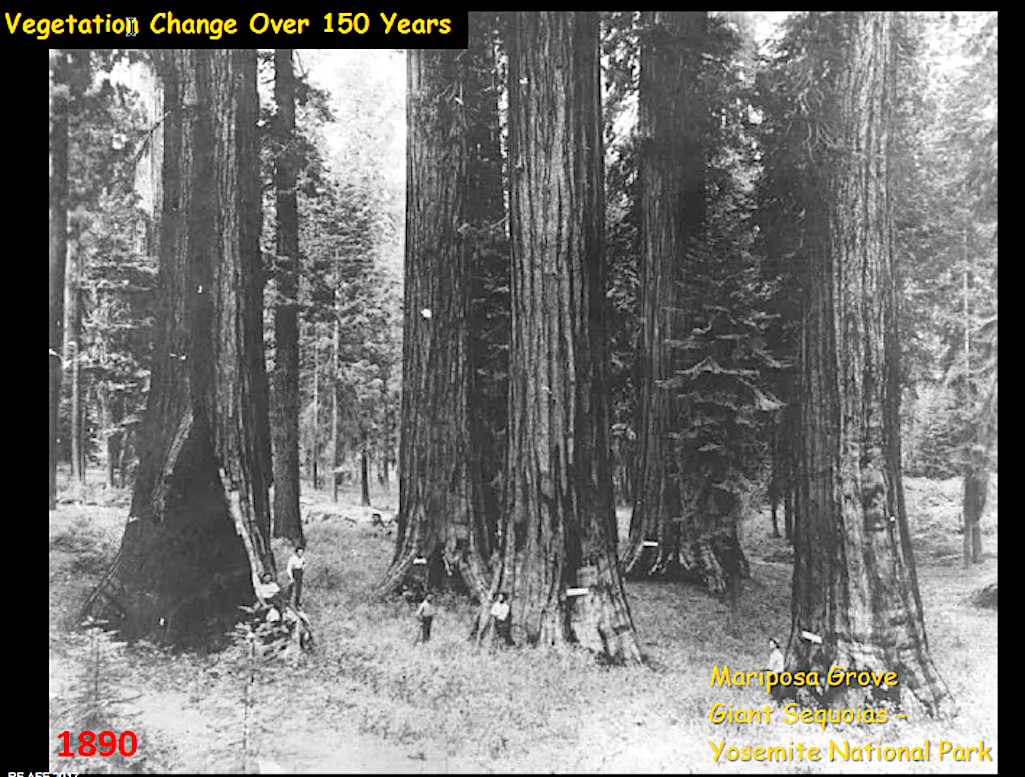

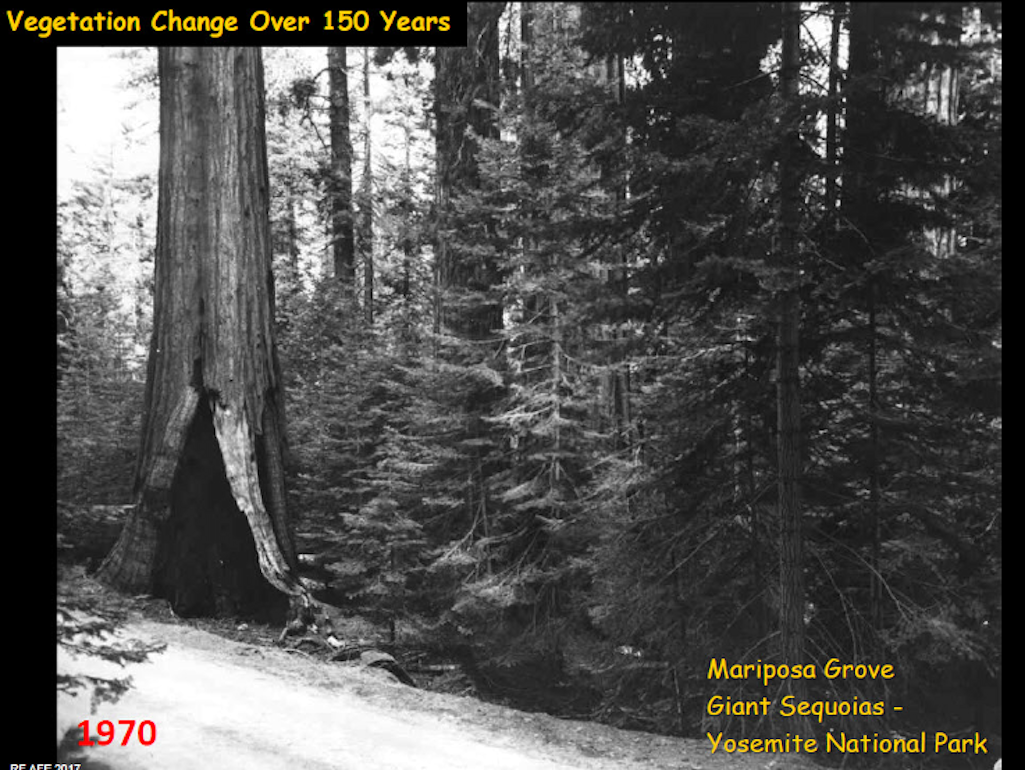

Today that same route would be almost impossible on horse or even foot, so dense are the thickets of pine, fir, and brush species. When trees are so crowded together, less light reaches the forest floor, and fewer grasses and shrubs are able to thrive. Those, of course, are the food that deer, bears, and birds depend on. A photograph of a Sequoia Grove in 1890 is typical of what Walker, Muir and other early visitors would see (Figure 2). A hundred years of fire suppression shows how drastically that same scene changed (Figure 3).

Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, 1890. Note the wide spacing of sequoias, the absence of other conifers, and how a person could easily ride a horse or walk through this grove, as remarked on by many early explorers.

Mariposa Grove, Yosemite National Park, exact same scene as Figure 1, in 1970. In 80 years without fire, the rise of dense conifers is significant. It’s now difficult or impossible to easily walk or ride a horse through this thicket.

The good news – both for our national parks and the approaching fire in Sequia National Park – is that the National Park Service fairly quickly recognized both the physical and ecological threat of full fire suppression.

In the 1960s, researchers began to publish papers on the effects of fire suppression in the West. Many of these papers built on the work of not only indigenous peoples – as their importance was slowly recognized – but on the purposeful burning of forest understory in the southeast of the United States where the practice continued in the early 1900s in spite of the full suppression polices adopted by forest agencies throughout the rest of the country.

One of the first research papers to come out was by Richard Hartesveldt, describing the fire-adapted needs of the sequoia cones and seed bed. He and others had noted there was a very long gap in the regeneration of Giant Sequoias: there were few very young sequoias. He was among the first to recommend restoring fire to the groves.

Adding to that record and beginning as in the early 1900s, a continuous tree ring record of Giant Sequoias had been developed. Extensive research in several groves established that before Euro-American settlers arrived, fire was very common. The tree ring record shows they occurred, on average, within a range of six to 35 years. Matching fire scars in tree rings within geographic areas showed those fires ranged in size from a quarter-acre to 900 acres. As occurs today, size and intensity of fire varied with climate. There were a number of very long droughts, especially between 800 C.E to 1300 C.E. (Common Era). This is important, because that period may point to similarities with today’s climate and fire effects on Giant Sequoias.

A study led by University of Arizona tree ring researcher Tom Swetnam concluded:

We suggest that preparation of sequoia groves for anticipated warming may call for increasing the rate of prescribed burning in most parts of the Giant Forest. (Swetman et al: Fire History of Giant Forest, Fire Ecology, Vol 5, No. 3, 2009)

The National Park Service in both Yosemite and Sequoia Kings Canyon acted on this early research fairly quickly and, by 1968, the first experimental controlled burns (now called "prescribed fire" and, more recently, "Good Fire") were being started beneath these ancient trees. Although denied the fire they needed for reproduction for much of the 20th century, that’s just a blip in their lifecycle. With obvious success in both regeneration and restoration of a pre-European forest environment, the NPS expanded its fire reintroduction to not only sequoia groves, but to much of their Wilderness areas, where it was safe to allow fire to return. Later, prescribed fire was adopted in many national parks of the West where fire played a role in those park’s vegetation dynamics.

The great tragedy, however, is that while from the late 1960s on the NPS had begun a robust program recognizing the science of fire ecology and reintroducing fire to their lands, there was almost no adoption of prescribed burns beyond that agency. In the rest of the West, with the exception of a few indigenous people’s on their ancestral land, most land-management agencies still followed a policy of full suppression when fires started. In those 50 years since we should have known better, forests have become more dense, brush thicker, the climate increasingly hot and dry. We have arrived at the catastrophic fire conditions we experience today.

There is good and encouraging news, though, for the Kings Canyon Complex which, at this writing, was moving towards the Giant Forest groves of sequoias. Since the 1960s, that area has had not only extensive prescribed fire around the groves, drastically reducing the understory thickets of conifers, buildings have been removed to restore the sense of ancient beauty and peace these groves can give visitors to the park.

In 2015, NPS fire restoration policy was given a critical test much like what its experience today. Then, the hot and fast-moving Rough Fire burned outside the park. It was fueled not only by the accumulation of conifers and brush that’s grown over the decades of full fire suppression, but through thousands of dead trees killed by bark beetles during a five-year-long drought California was going through. It burned into the northern edge of Grant Grove in Kings Canyon National Park that had also been extensively treated by prescribed fire since the late '60s. Anthony Caprio, a fire specialist in Sequoia and Kings Canyon, and his colleagues began surveying the grove even as it was still burning in places.

They had maps of each historic prescribed fire, as well as “before” photos, they could use to assess relative effects of fire in the treated and untreated areas (Figure 4). The differences were dramatic.

Relative fire severity (from red –severe – to green – less severe) of Rough Fire (2015 Sequoia National Forest and Kings Canyon National Park). Green inset at lower right shows treated areas of Grant Grove overlaid on the fire intensity map. Note lower fire severity (red) in that area.

Tony summarized their results in a presentation he gave:

•Patterns of sequoia tree mortality were observed within the area burned by the Rough Fire.

•Direct fire caused mortality of small trees was seen throughout the burn.

•No direct fire caused mortality was observed in medium or large trees in the area treated with prescribed fire, where fuel loads and tree density had been reduced, even though the fire occurred during an extreme drought.

•There are recent observations (fall 2017) of delayed mortality of monarchs (drought stress, fire, bark beetles), primarily in the untreated area. This mortality is in areas not severely burned by the Rough Fire. This was not expected and is being investigated further by USGS and NPS staff.

Rapid establishment of Giant Sequoia seedlings following 2015 Rough Fire. Seeds released by the heat of the fire fell on the bare ground cleared by the fire and sprouted.

The beneficial effects of prescribed fire is seen not only in sequoia groves but in other places fire or thinning treatments (cutting trees and other vegetation by hand) is done. The ongoing Caldor Fire near Lake Tahoe is a good example. Multiple agencies in the Tahoe Basin worked together to coordinate clearing, cutting, and burning around their communities. When the Caldor Fire reached there, flame lengths went from as much as 150’ to 15’ as the fire entered the treated areas. As a result, firefighters were able to make a stand and protect lives and property. No structures were lost in South Lake Tahoe.

Mosaic Fires

Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California also has an extensive history of prescribed fire. Recently, the still-active Dixie Fire in burned though much of the park. However, initial surveys showed a classic fire behavior. There were certainly areas of intense fire, burning 100 percent of trees. But there were also areas of much lower intensity fire, flaring up in places but in others just moving beneath the forest canopy and reducing ground litter, logs, and low branches that all act as ladder fuels which, under extreme conditions, can carry a fire up into the forest canopy.

The combination of hot fire with higher mortality and areas of cooler fire is called a mosaic effect. Because that mosaic creates an ecosystem of open meadows, less dense forest, and even areas of fire-killed trees, we start building an ecosystem where fire may not be as catastrophic in the sense that they burn hot, non-stop for days and weeks. The varied ages of trees, the open forest, and reduced dead forest litter all combine to reduce the intensity of fire and, so, rate of spread. Most can then be stopped earlier and prevent the loss of communities.

To be sure, widespread reintroduction of fire will not be easy. The buildup of understory fuels and dead tress is significant in our brush and forest vegetation types. Critically, a major percentage of California’s communities are in what’s called the Wildland Urban Interface. These are the places we’ve all read about in the last five years where entire communities were lost. The approach will likely have to involve a combination of clearing by hand and safely burning piles and, where safe and indicated, use prescribed fire for large areas adjacent to those cleared areas that can act as fire breaks.

The 2020 North Complex fire near Quincy in northern California. At left, it completely burned an entire forest but, when it reached the edge of areas treated and thinned by the Plumas Fire Safe Council, intensity lessened dramatically.Sierra Nevada Conservancy

There are also significant environmental considerations. Air pollution control districts set days that fires can burn. Those days often can’t be predicted far in advance. Environmental regulations and permits need to be written up and signed off on and the burn needs to be planned well ahead of time. Trained burn bosses, crews, and equipment need to be gathered to decide on the area to be burned, and to consider the “prescription” (humidity, temperature, wind, fuel moisture etc.) to be followed on when to burn and how long the area needs to burn completely. As noted, the burn days then have to coincide with those approved by the air pollution control district.

It may be that such days might need to be expanded a little. This is a critical decision to aid the total number of days burns can happen. Smoke is a serious health danger to many people with asthma and other breathing problems. The trade-off might be a few days of smoke vs. the weeks we’re now experiencing of dense and dangerous smoke over much of California and the West. Worse, we are likely to have many years of both until clearing and prescribed fire can start to have an effect on reducing the catastrophic large fires.

Nor are the ancient Giant Sequoias safe. Last year, extensive fires burned throughout the southern Sierra and into many groves of Sequoias outside the National Parks. Most of those groves had never been thinned or burned. Thousands of Sequoias, including many of the huge Monarchs, burned. Researchers agree that prescribed burning must be increased in our groves to protect not only our Giant Sequoias but our communities and landscape.

There’s really no choice. We can either keep spending billions on total fire suppression, increased insurance costs of lost homes, and the trauma of deaths and dislocation of communities, or follow a path to forest and landscape resiliency. The latter recognizes fire as integral to forest health and regeneration. Prescribed fire is not meant to stop fire, we’ve already made that mistake, but it will allow fires to become more manageable when near communities, where they can likely be stopped.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

This is the best relatively short article I have read that describes the history, ecology, and management of fire in the western U.S. It should be required reading for policy makers. Thank you!

George has written an excellent article on the history and benefits of prescribed fire. As one of the managers of the program which conducted such burns in Giant Forest over the years, it is most gratifying to see how effective they have been in protecting the trees from wildfire. One point of clarification in his article: many state and federal agencies did in fact adopt a prescribed fire policy. The problem has been the well-documented shortfall in the implementation of prescribed burns in the western U.S. , a problem the NPS shares. There are many reasons for this shortfall in accomplishments, such as funding, staffing, environmental compliance issues, risk aversion, and wildfire activity in wildland urban interface areas. One of the lessons of the Giant Forest prescribed fire program is that such programs must be sustained over time, on a regular cycle, to maintain their effectiveness. The Giant Forest burns were often conducted during the summer, while wildfires were burning elsewhere. It's easy to find reasons to postpone a prescribed fire, but the wildfire risk remains, and compounds over time. The recent heavy mortality of giant sequoias in untreated areas sadly illustrates the consequence of inaction.

Of course the Forest Service is the biggest agency with forest lands in the United States, and I heard that because of the way their firefighting budget was set up, they would have to put off prescribed burning because the money was redirected towards firefighting. But there was enough movement in Congress to change the way that it's budgeted.

It's very ironic to realize that Bob Barbee, who was resource management specialist in Yosemite in the early 1970's, is one of the people who first researched and realized the historic role of fire in protecting the Big Trees.

Back then, when he recommended using fire in the groves, he met terrific resistance. But what really set off a firestorm (pun intended) was when he pointed out that without fire, a very heavy growth of mature sugar pines and ponderosa had developed in the groves and that if they were ever torched off, the Sequoias were goners. His proposal to go in log those trees out before burning set the Sierra Club and other groups off big time. The explosion rivaled Krakatoa.

And then, when Yellowstone burned in 1988 and Bob was superintendent there, he was crucified by many in the public and media for "allowing" the park to burn.

We all owe a big debt of gratitude to Bob Barbee.

For sure. I'd forgotten about Bob Barbee. I worked with him briefly in the 70s and he was a very early advocate of prexcribed fire in NPS. He was inspired by the work of Harold (The Torch) Biswell at UCB and Dick Hartesveldt. Who, themselves, were inspired by ongoing Rx fire in the SE US and, of course, Native Americans. Later, students of both took lead roles in advocating for fire in the US.

To get an 'attaboy' from Tom Nichols (who's been in Sequoia since the late Pleixtocene) makes me blush. Hi tom!

And a tip of the hat to Matt for same.

I should add that most of the images are from a great slide deck Tony Caprio (SEKI NP) presented some years ago: Did Prescribed-Fire Treatments Moderate Effects of the 2015 Rough Fire on Giant Sequoias in Grant Grove, Kings Canyon National Park?

This is vital information we all need to know. It sould be placed in all of Califonias" major newspapers. GEorge Durkee is a former long time national park ranger in Sequoia /Kings National Park....an expert on the information he has gathered over the years.