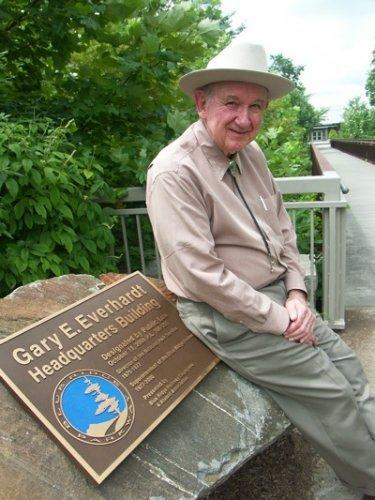

Gary Everhardt, the ninth director of the National Park Service, has died/Randy Johnson file

Gary Everhardt, who turned down a career path with Boeing to pursue one with the National Park Service, a move that saw him rise to become the agency's ninth director, has passed away, just days after his wife died.

The 86-year-old Everhardt died Sunday evening, four days after his wife, Nancy. Both died from Covid-19, according to the Park Service.

“We are deeply saddened by the loss of both Gary and Nancy,” Phil Francis, chair of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, said Tuesday. “All of us who work for and with the National Park Service are indebted to them for their devotion and service. They will be long remembered. We extend our sincerest sympathies to Gary and Nancy’s children and their families and friends for their loss.”

Gary and Nancy (Poovey) Everhardt were raised in North Carolina, not far from the Blue Ridge Parkway. Everhardt began his NPS career on the Blue Ridge Parkway in 1957, where he served as a civil engineer. He had interviewed with Boeing Aircraft and the Navy Shipyard in Norfolk, Virginia, he recalled in a 2010 interview with the Traveler, but couldn't get excited about those jobs.

“Then I had an offer from the Park Service, for an engineering job," he said. "I thought that would be a lot better than sitting at a desk in Seattle, Washington, doing stress analysis on airframes, or working in the Navy Yard at Newport News. I jumped at it. It all kind’a happened by accident in some respects.”

As with most Park Service employees, Everhardt moved around the country with the agency, heading west to serve as the Park Service's regional chief of maintenance in Santa Fe, New Mexico, a role he held for four years before moving to Yellowstone National Park in 1969 to serve as assistant superintendent for operations.

Three years later Everhardt was named superintendent of Grand Teton National Park, where he earned the Department of the Interior’s Meritorious Service Award for helping to plan and execute a global national parks conference during the National Parks Centennial.

In 1975, under the Ford administration, Everhardt was appointed Park Service director. During his short, two-year tenure, he oversaw an increase in park development and interpretive programming for the bicentennial of the American Revolution, and oversaw a 32-million-acre expansion of parkland in Alaska.

“It was a key time, essentially determining how Congress was going to divide up these pristine lands between the Park Service, Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the state. The Park Service doubled its acreage,” Everhardt told the Traveler.

As director Everhardt also focused on enhancing the parks and received authorization to add 1,000 Park Service jobs to assist with the celebration of America’s 200th anniversary.

Following his time as director, Everhardt returned to the field as superintendent of the Blue Ridge Parkway, a position he held for the last 23 years of his career. Under his leadership the Parkway forged partnerships with The Conservation Trust of North Carolina -- leading to the protection of tens of thousands of acres along the Parkway -- and the Blue Ridge Parkway Foundation, which provided millions of dollars for Parkway resource and facility protection.

“The great thing,” Everhardt said in that 2010 Traveler interview, “is that people are starting to act. The conservancy land groups are stepping up to the table with real money. With a little bit of federal partnership, we can work wonders.”

Everhardt oversaw the completion of the Parkway headquarters building, as well as the Linn Cove Viaduct. In honor of his service, the headquarters facility was named after him.

The North Carolina native also brought mountain music to the Parkway in the form of the Blue Ridge Music Center.

On the 50th anniversary of the Parkway, Everhardt and others were attending ceremonies near Cumberland Knob. “We’d been listening to all that great traditional music and got to talking one night. You know, spitting into the fire, drinking something, and somebody said, ‘We need a music center,’” he told the Traveler.

“During my time in Washington, I used to go out to Wolf Trap (America’s National Park for the Performing Arts in Virginia) and I loved what they’ve done there. The National Park Service could say, ‘We ought to stick to preserving natural resources,’ but the Parkway is a kind of music trail. I thought a music center was a great idea,” said Everhardt.

His 42-year career with the Park Service was recognized by the state of North Carolina, which presented him with its highest honor, the Order of the Long Leaf Pine Award.

In 2014, Everhardt joined the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, becoming the 1,000th member of the organization.

Comments

The conference was "The Second World Conference on National Parks," led by Gary and held at Gary's Grand Teton National Park and Yellowstone National Park.

I speak to Gary's involvement with the heritage music center elsewhere on this site. https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/podcast/2020-09-27-national-parks-...

It was the 100th anniversary of Yellowstone.

Delegates came to Jackson Lake from all over the world, and shared cutting-edge ideas. It was the great notion of then-Director George Hartzog, as the showcase and revelation of Hartzog's innovations and aspirations for parks.

But many NPS people who attended learned a great deal, perhaps to their surprise, from the international delegates and their parks' experiences.

Gary tended, but did not preside, over the passage of Alaska National Park proposals, which ultimately exceeded this acreage.

That happened later.

Gary did reorganize the Alaska Planning Group, bringing in the avid and talented park superintendent Roger Contor, of Rocky Mountain National Park, to infuse operational sensibility into the Washington effort, and put the planners in the field (several were working for each of the new area proposals or expansions) under Region Director Russ Dickinson and state director Bryan Harry. This was a heavy lift but Gary did it.

He also urged the Ford White House to jump-start the legislative proposals that then seemed to be languishing - with several presidential proclamations, as National Monuments.

LBJ, famously, gave up the same idea in the last day of his administration in 1969.

Ford gave it serious consideration but, ultimately, chose to wait for Congress. The word was Senator Stevens (R-AK) wanted the hold thinking he could get the best possible deal to compromise the parks by waiting until the deadline.

While trying to keep the Alaska dream alive, and while restructuring the line of direction of the planners by the DC Alaska Planning Group, Gary was also dealing with the issue of Mining In The Parks.

In fact, on the day the designer of the park proposals and head of the Alaska Planning Group in DC, Ted Swem, walked out, confronting the Director with a power vacuum, Gary was dealing with the future of Death Valley, too.

He called in 3 from the DC legislative team to meet with his special assistant Bill Everhart and his Assc Director for Operations John Cook, to figure out what to do with Swem out.

But Gary had just been raked over the coals by the Sierra Club, in their suit over mining.

Gary had just finished a grueling affidavit with the Sierra Club, the thankless task of admitting mining hurt parks while not contradicting Ford Administration policy to keep mining going in Death Valley.

The Ford Administration did not want to fix the law. Gary did. It is (until the last 10 years or so) the tradition for the NPS to work to cure the flaws in original legislation of new parks.

We saw this more perfect evolution with Grand Canyon. We saw this with Yosemite. Now was the time to deal with the damage from mining. The Mission of the National Park Service is to live up to the Act of 1916.

But instead of scheming about Alaska, Gary was fuming about mining. And when the Director fumed he could turn the air blue.

He turned on Cook and Bill Everhart (no relation):

" G__ f____ D____, it Cook and Everhart: the ___ ___ Sierra Club !!! They act like they think we are trying to ruin the parks!" He glared at John and Bill: "Do they think we are f____ trying to RUIN the parks!!???"

Cook was dipping tobacco and fiddling with his paper cup. Bill slowly looked up at the enraged Director.

"Uh-huh." Said the loquacious Bill Everhart.

That was not the answer the Director required. He stormed around for another 45 minutes. He looked at Cook and Everhart even harder. Cook fiddled with his cup.

"G__ f____ d___ it ! Cook ! Everhart! GET ME OUT OF THE m_____ ____ MINING BUSINESS!!!!"

Cook saw something interesting on the back of his cup.

Bill Evethart: "I wasn't aware I got you into the mining business. . . "

But despite the Ford Administration, and with the professional support of Gary Everhardt, the Mining in the Parks law passed.

And the Alaska effort was reorganized, which did lead to much larger recommendations, but under Director Whalen primarily led by Secretary Cecil Andrus.

Ironically, or perhaps because of his time in Washington, years later Gary was frustrated in the extreme by the Washington Office staff. He once accepted a training meeting for Virginia superintendents on the provision that I promise that no WASO associates or asst dirs would join us.

But Gary mostly as I remember him had a big affable way about him, and a big welcoming smile. I am sure that George Hartzog, from the same country, took to him immediately. A further irony, the same Nat Reed, conservation hero, who was an early advocate of George Hartzo's retirement, acted as talent-spotter of Gary, saying that the superintendent of Grand Teton National Park was the best superintendent in the Service, who was definitely Director material

And so, like with Gary and mining in the parks, had Gary been in Washington in recent years he would have worked to cure crucial problems in the Alaska bill as compromised.

Such as the section 201(4) clause of ANILCA designed to ruin the Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve with an ore-haul road crossing the park boundaries TWICE to enable an open pit toxic copper mine on the margin of 4 national park units and the Kobuk Wild River.

If no bureaucrats stirred themselves to make the case to Congress about needed repairs of the Alaska Lands law, you can bet Gary would have set them straight, bellowing: "GET ME OUT OF THE m____ _____ MINING ROAD BUSINESS!!! "