On a recent morning in Everglades National Park, the predominant sound at the Flamingo Visitor Center wasn’t park rangers giving a lecture or visitors shopping for souvenirs, but the buzzing of electric saws, hammers, and other construction equipment. This park building—an icon of the National Park Service’s ambitious Mission 66 program—is now undergoing a complete rehabilitation and is expected to reopen to visitors in summer 2021.

Like its feathered namesake, the Flamingo Visitor Center is pink, long-legged, and emblematic of south Florida. Designed by prolific NPS architect Cecil John Doty (working with a Florida architect named Harry Keck) and completed in 1957, the visitor center was one of the first completed Mission 66 buildings.

Mission 66 was a ten-year plan for new building architecture, landscape architecture, and engineering projects across the National Park System that was meant to prepare the parks for a post-World War II explosion of vacationers hitting the highways, and culminate in the agency’s 50th anniversary in 1966. The ambitious program embraced the mid-century modern aesthetic of the period and produced some of the parks’ most distinctive structures, including the Clingman’s Dome observation tower at Great Smoky Mountains, the Painted Desert Community Complex at Petrified Forest, and the now-demolished Cyclorama building at Gettysburg.

When the National Park Service moved away from the rustic architecture that characterized many iconic lodges and structures that rose in some of the Western parks in its first half-century, Doty transformed along with it, transitioning his work from a more vernacular to a more modernist aesthetic. Above all, according to architectural historian Sarah Allaback, Doty’s work across the park system embraced each site’s natural beauty, orienting views towards the most scenic vistas. His designs, Allaback wrote in her book Mission 66 Visitor Centers: The History of a Building Type, “are sensitive to the site and the historical context without being cheap rustic imitations or modernist spectacles.”

The Flamingo Visitor Center is a classic example of Doty’s approach. Designed to be the centerpiece of Flamingo, the visitor use area on the southern tip of the Everglades reached via a 38-mile drive through a landscape of cypress trees, pinelands, and scrub palmetto dotted with snowy white egrets, the visitor center is a wide, asymmetrical building featuring a long central breezeway connecting two anchor buildings overlooking Florida Bay. Notably, the complex shimmers in its bright pink exterior, a nod to the colorful Miami Modern aesthetic. The center was designed as part of a larger visitor use complex that included a restaurant inside the visitor center building as well as a gas station, lodge, and boat dock.

“We were one of eight parks that piloted Mission 66 programming,” says Allyson Gantt, a spokesperson for Everglades National Park. “You’ll notice that the visitor center and this particular breezeway frames the Florida Bay. So it’s a modern structure but it also integrates a lot of the natural elements around it.”

From Plume Hunter To Game Warden

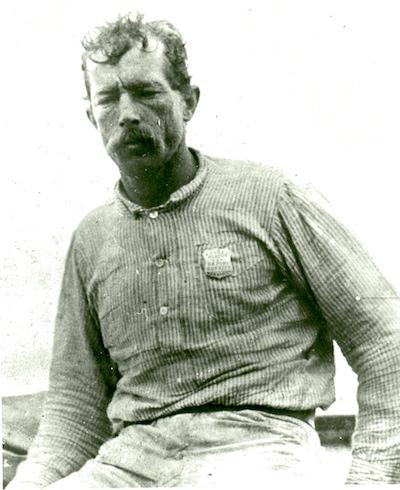

Guy Bradley, like some other conservationists in the late 19th century and early 20th century, converted from profiting from wildlife to protecting it. As a 15-year-old in 1885 he and his brother worked with hunters who headed to the Everglades to kill egrets, herons, and other wading birds for their plumes that were fashionable in ladies’ hats at the time.

Passage of the Lacey Act of 1900, which made it a crime to poach wildlife for the purposes of selling it for profit, convinced Bradley to change his ways. In 1902, the American Ornithologists’ Union hired him to serve as a game warden in the Everglades.

Three years later, while responding to gunshots he heard not far from his home at Flamingo, the young warden was shot to death by one of the men he confronted. His body was found in his skiff the next day, having floated 16 miles from where he was shot.

“During all this time he faithfully guarded his wards, the plume birds, traveling thousands of miles in the launch Audubon, in order to watch over them...A number of well-known ornithologists and members of the Association visited Bradley at different times, and always found him alert and faithful in the performance of his duty, and willing to undergo any hardship to protect the birds. He took a personal interest in his work and was genuinely proud when he could report an increase in numbers,” wrote William Dutcher, a New York businessman who supported the Ornithologists’ Union, in an obituary that ran in Bird Lore.

The Audubon Society later established the Guy Bradley Award that is presented annually to wildlife officers for exceptional service. At Flamingo, the Guy Bradley Trail is a mile-long short cut from the Flamingo Visitor Center to the Flamingo Campground day-use area.

In 1930, Marjory Stoneman Douglas published a fictionalized account of Bradley’s life, called “Plumes,” in The Saturday Evening Post. “His face quieted with the same passionate and mute intensity,” she wrote of the Bradley character, “that inward absorption, that the bird’s eyes held, still clinging to its branch.”

Doty’s design wasn’t without its detractors; many viewed the rustic “parkitecture” that Gilbert Stanley Underwood mastered with the Bryce Canyon Lodge, Zion Lodge, Old Faithful Lodge, Cedar Breaks Lodge, and Grand Canyon Lodge as emblematic of the National Park Service. To them, the designs coming out of Mission 66 were too industrial.

But Conrad Wirth, the Park Service director who ushered in Mission 66, and Doty won out. As Kyle Pierson wrote in "The Flamingo Lodge: Florida’s Mission 66," which appeared in The Journal of Florida Studies, Doty “thoroughly embraced Modernism.” Thomas C. Vint, the Park Service’s landscape architecture chief from 1927 to 1960, also welcomed this new approach for the park system.

As the years passed, the visitor center exhibits grew outdated, and the building showed signs of wear and tear in the form of peeling paint, cracked and spalling walls, and overgrown vegetation. “Very old & run down,” wrote a TripAdvisor commenter in 2017. “Not much to see on the inside of the center or the outside.”

Although it had weathered numerous storms over the decades, Hurricanes Wilma and Katrina in 2005 and Hurricane Irma in 2017 were particularly damaging. In the face of the even more devastating storms expected with climate change, it was clear that the visitor center needed a full rehabilitation.

In 2016, the national park and the South Florida National Parks Trust won a $250,000 historic preservation grant to restore the visitor center, which has been bolstered with other public and private funding. The center is itself part of a major overhaul of the Flamingo area that will include a new restaurant and lodging as well.

Croft & Associates, a Georgia-based architecture firm based with extensive experience working in the national parks, is the lead designer for the renovation. Work includes structural improvements to meet 180-mph wind standards, a full roof replacement, and a complete interior renovation to include a museum and information area, law enforcement headquarters, and staff offices.

“Flamingo’s visitor center was designed for resiliency to Category 5 storms, while respecting the historic structures and landscapes that have remained largely untouched for six decades,” says Ed Setzler, the NPS program director for the firm. “While it would have been tempting for a design team to rework the exterior landscapes, respect for the historic Mission 66 character of Flamingo was paramount throughout the creative process.”

Setzler notes that the visitor center area is convertible into a glamorous event space for meetings, receptions, or other functions, which is designed to emphasize a connection with the surrounding landscape. Someday soon, he says, the great hall at Flamingo will be “one of the premier ecologically themed spaces in America.”

When completed, the center will be named for Guy Bradley, an ardent bird-lover and game warden who was killed doing his duty to protect birds in the Everglades from hunters. The Park Service proposed the name to “honor [Bradley’s] life and his historic conservation achievements.”

Comments

Spent several days in The Flamingo area of the Everglades, several years ago. Visitor center but no place to stay, other than the campground with all the mini rattlesnakes. No Thank you!. This will be great for the Evergladesand the National Park Sevice!

So glad to see this happen. I ran the Flamingo VC from '81-'83 and returned as Chief of Interpretation at Everglades from 2000-2007. During both of my tenures there, the VC desperately needed attention.We did the planning for new exhibits during my first stint there. When I returned 17 years later, the "new" exhibits were as tired and sad as the ones there in the early eighties. Flamingo is a fantastic place, offering world-class visitor experiences. It deserves world-class interpretation.

I work and live in Flamingo for over 20 plus years and I must save, it is great to see Flamingo Visitors Center being revitalize.

I visited Everglades NP as child in 1958, ate at Restaurant at Flamingo. Was so disappointed, when showing my hubby the area in 2012. I am glad they are going to restore things, maybe we will come back in 2021. We have visited & stayed at many National Parks. By far Yellowstone & Grand Canyon North Rim, are the best.. I am from Miami area originally too !

I have been to Flamingo twice, First in 2016 when the visitor's center was in the left end of the building in the picture and the "resturant" was a food truck behind the building. It was still enjoyable. The second time the "visitor's center' was in a temperary trailer in the parking lot due to storm damage to the building. I fell in love with the Everglades because of Flamingo, and it is my plan to return again, hopefull after the new visitor center and resturant are finished.