Wild bulls, orphans, and a brave Keeper converge at a waterhole, Tsavo East National Park, Kenya/Barbara Moritsch

In August of 2009 an elephant calf was seen wandering alone near Kenya’s South Turkana National Reserve. No one knew why it was alone. Its mother may have been killed for ivory or meat, or may have perished from drought, illness, or injury. The calf was entering an extremely dangerous conflict zone. The common intertribal raiding in the region had intensified because of drought; there was little water or grass for livestock. Despite the danger—the tribes were armed with automatic weapons—a team of people caught the calf and took it to a rescue facility adjacent to Nairobi National Park. The female calf was about four months old. They named her Turkwel, after a village and river near where she was found.

Seven years ago I discovered the website for the rescue organization, the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust (now Sheldrick Wildlife Trust). I decided then and there to foster Turkwel because, well, how can you not love a baby elephant named Turkwel? Fostering an orphan costs $50 per year; I now foster three. I get monthly updates on their status, and stories of new babies who may have been found trapped in a well or latrine pit, or crying over the mutilated body of their mother, poached for her tusks. Rescues occur frequently all over Kenya, within and outside of protected areas.

Last October, I got to meet dozens of the orphans firsthand, as well as numerous ex-orphans now living wild, and was immersed in one of the world’s most successful wildlife rescue programs. This work is happening within, and in collaboration with Nairobi and Tsavo national parks, and with the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), which administers Kenya’s national parks. This world renowned program was launched by a women with deep passion and a strong commitment to wildlife: Dame Daphne Sheldrick.

Older orphans hold their own formula bottles during an afternoon feeding, Umani Springs, Kibwezi Forest, Kenya/Barbara Moritsch

Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

In 1977, with support from the African Wildlife Foundation, Daphne established the David Sheldrick Wildlife Appeal in memory of her late husband, the founding warden of Tsavo National Park and a wildlife conservation leader. The organization became independent in 1987 and was re-named the David Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. In April of 2018, Daphne Sheldrick passed away. In accordance with her wishes, the name is now the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust. The work of the Trust carries on under the direction of Daphne’s daughter, Angela Sheldrick, as well as other family members and a very dedicated staff.

Daphne lived in Tsavo and near Nairobi National Park for many years, and rescued a wide variety of species, including elephant, rhino, zebra, Cape buffalo, impala, kudu, eland, civet, mongoose, warthog, and ostrich, among others. Through trial and error, she learned how to help them survive and thrive. She determined, for example, that rhinos and zebras did well on Lactogen baby formula, and baby elephants could not tolerate cow’s milk. In a last ditch effort to save one young elephant, she tried a formula containing coconut oil—and it worked. This same orphan taught Daphne that elephants can become too attached to humans; he became ill due to separation anxiety while Daphne was away, and died soon after she returned.

The Trust helps many different species in need, but most of their efforts go to elephants. As of January, 2019, the Trust’s Orphans Project was supporting 19 elephants, 1 black rhino, 1 giraffe, and 1 very young white rhino at their Nairobi Nursery, and 62 elephants at reintegration units. To illustrate the program’s success, 150 rescued orphan elephants are now living wild; and in 2018, the 30th baby born to a wild ex-orphan came into the world. The staff are eagerly awaiting the imminent arrival of number thirty-one.

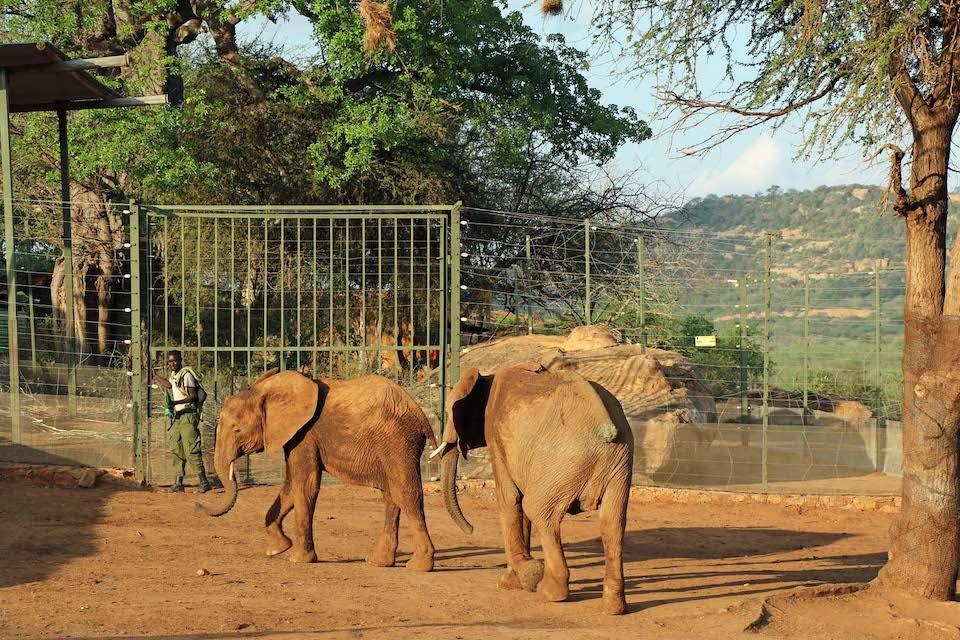

Turkwel and friends at Ithumba Stockades, Tsavo East National Park, Kenya/Barbara Moritsch

In addition to caring for the orphans, the Trust protects them after they return to the wild. Together, the Trust and KWS operate nine Anti-Poaching Units (eight in the Tsavo area); four Mobile Veterinary Units; and an Aerial Surveillance Unit.

Nairobi Nursery

The first stop for rescued orphans is the Nairobi Nursery, adjacent to Nairobi National Park. This was also our first stop. At the nursery we watched the orphans’ 11 a.m. bottle feeding; an evening feeding followed by a visit with the babies in their pens (stockades) and their caretakers (known as Keepers); and an afternoon feeding, after which we mingled with the elephants as they took dust baths, browsed in the adjacent bush, and tried to steal flowers planted around the facility. This latter visit—one of the most incredible experiences of my life—was private, for just our small group. I’m hard-pressed to describe it. Nothing compares to standing in the middle of a herd of about 20 young elephants, each weighing from 300 to over 1000 pounds, as they go about their business. They were polite, calm, and completely unafraid of people. Occasionally one would pass very close by on its way to a desired cluster of leaves, so, while you were photographing one, another would bump you from behind. The bumps were never serious, and I wondered if the orphans viewed humans as oddly-shaped elephants.

When orphans arrive they get needed veterinary attention and then 24/7 care from the Keepers, who work hard to stand in for the orphans’ lost elephant families. Keepers spend nights on raised platforms with the infants, and rotate frequently so no one becomes too attached (the attachments do go both ways). Initially, orphans are fed on demand, frequently and in small quantities, and eventually they settle into feeding every three hours. National Geographic writer Charles Siebert once asked a Keeper if he used an alarm clock to wake up for feedings. The Keeper said no, every three hours the baby would reach up with its trunk to pull the Keeper’s blankets off (National Geographic Magazine, September, 2011).

Young orphaned bulls testing their mettle, Ithumba Stockades, Tsavo East National Park, Kenya/Barbara Moritsch

Elephants are tactile and social, so Keepers provide a lot of physical contact, talk to the orphans, and demonstrate affection. Very young babies are provided with blankets, rain gear, sunscreen, or an umbrella when needed. Keepers and orphans go for walks daily in areas around the nursery and play with sticks and stones, as well as rubber tubes and balls. An important milestone has been reached the first time a baby plays; experience has shown that the orphans will thrive only if they’re happy.

Weaning begins at three to four years of age, when calves start eating more vegetation, including a variety of plant species and tree bark. When the orphans are deemed physically and emotionally ready to be moved, which can take up to ten years, they are transferred to either the Umani Springs stockades in the Kibwezi Forest, or the Voi or Ithumba stockades in Tsavo East National Park.

Umani Springs

A 3½ hour drive south of Nairobi took us to our second stop: Umani Springs, a reintegration facility built in 2014. As one of the Trust’s Saving Habitats projects, this 16,000-acre area is cared for in partnership with the Kenya Forest Service. The Trust secured a 30-year concession to manage and protect this part of the Kibwezi Forest, which borders the Chyulu Hills National Park and supports one of Kenya’s last remaining groundwater woodlands. The forest area is considered an exceptional biodiversity hotspot and is part of a huge network of protected areas, the Tsavo Conservation Area.

An orphan emerging from a cooling mud bath, Tsavo East National Park, Kenya/Barbara Moritsch

We spent two nights at Umani Springs at a beautiful lodge owned and managed by the Trust. Our days were spent with the 12 orphans at the Umani facility, watching them feed, browse, bathe in dust piles and mud pools, spar with one another, and scratch their large, itchy bums on the loading dock.

The stockade facility and surrounding habitat at Umani Springs are well-suited for orphans who have suffered injuries or ailments. This is in contrast to the harsher, dry environment of Tsavo, our next stop on the tour.

Ithumba

We left Umani Springs reluctantly, the site and lodge were lush and gorgeous, and the food was incredible. A two-hour drive took us to Tsavo East National Park and Ithumba. Together, Tsavo West and Tsavo East form one of the largest national parks in the world, covering 4% of Kenya’s land area (more than 8,800 square miles or 5.6 million acres). The larger park, Tsavo East, is a vast, mostly flat expanse dominated by semi-arid grasslands and savanna. It’s considered one of the world's biodiversity strongholds, and is known for its large herds of red elephants, which acquire their color by wallowing and dust-bathing in Tsavo’s lateritic soil. Other species present include black rhinos, buffalos, lions, leopards, cheetahs, giraffes, hippos, crocodiles, waterbucks, lesser kudu, gerenuks, zebra, and Hunter’s hartebeest, a critically endangered antelope, among others. Over 500 bird species have been seen in the park.

At Ithumba Camp we shared our large canvas tents with geckos and agamas, and showered outdoors, sometimes in the company of a curious yellow-billed hornbill. The camp also hosted a troop of over 25 baboons, a biscuit-stealing vervet, and lots of dik-diks and squirrels, and we had visits from lesser kudu, warthogs, and a genet. We visited with the elephants three times a day, and every day was different. At the Ithumba stockades and watering holes, the Keeper-dependent orphans were always present, but we were continually surprised by the number and diversity of other elephants (and one bold buffalo) who came to visit the stockades. Dozens of ex-orphans, some with wild-born babies, as well as small, medium, and extra-large wild bulls made frequent appearances.

We did not visit Voi, the third reintegration unit built in 1948 by David Sheldrick when he was warden of Tsavo East

Going Wild

At reintegration units the orphans assimilate into wild elephant communities. They walk far and wide in the bush with their Keepers, where they encounter the wild ones. In general, the orphans are welcomed by the wild elephants and are allowed to play with wild age-mates; they’re tolerated as long as they behave well. At night they return to the stockades with the Keepers.

The author meets one of the young orphans, Umani Springs Stockades, Kibwezi Forest, Kenya/Sheldrick Wildlife Trust

Ex-orphans living wild often come to the stockades and take a Keeper-dependent orphan out for a trial night in the wild, but sometimes the aspiring graduate feels insecure after dark without human protection. When this happens, the orphan is escorted back to the stockades, usually by a couple of ex-orphan bulls, and returned to the Keepers and the security of the stockades.

The reintegration process varies for each individual. The orphans themselves decide when they’re ready to join the wild herds. After they go, many of the “wild” ex-orphans return to the stockades to visit, or when they need help. They know their human family will be there for them. This is what happened with Turkwel.

In April of 2013, Turkwel moved from the nursery to Ithumba, and by mid-2016 she was living wild with a herd of ex-orphans. On July 24th, 2018, she returned to the stockades with serious injuries from a lion attack. The Keepers cleaned and treated deep puncture wounds around her tail and hind legs and she spent the night in the stockades, while her herd stayed just outside the pens. Apparently it was a very restless night for everyone, and the next day Turkwel broke out of the stockade area and did not return until August 5th. By then, her tail was very infected and a vet was flown in to treat her, which included amputating her tail. After this, she stayed at the stockades for several months while her wounds were treated daily. She was healing well when I saw her at Ithumba in late October. In late November she left the stockades with her herd to live wild once again. On the night of December 20th she paid a visit the stockades, and all was well with Turkwel.

If you are interested in supporting the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust, you can make a tax-deductible donation through the U.S. office (https://www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org/html/help_USA.html), or foster an orphan (https://www.sheldrickwildlifetrust.org/asp/fostering.asp). Foster donations support the Orphans Project’s direct costs—rescue, transport, milk and other foods, maintaining stockades and fencing, vehicle maintenance, and Keeper salaries and quarters. If you’d like to visit the orphans, several companies provide tours, including the company I used, Capture Africa Tours. And, yes, I’ve already booked again for 2019—I’m hooked.

Comments

Great article Barbara, I learned a few things from a it that I didn't know from when we were there. I love the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust and what they do for the rescued Elephants and all the Wildlife in their care.

i am a proud Sponsor of four of the Ellie's and Maxwell the Rhino, I will continue to sponsor them as long as I am able.

Thank you for such beautiful and informative article.

Barbara, this is such an excellent article and perfectly describes our encounters with the orphan elephants at the three Sheldrick units we visited. Thank you for writing it, for bringing back such wonderful memories and for presenting the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust to the word in such a passionate way.

Thank you, Dorothy!

Thank you, Betty!

What a great, informative article! As I started reading, I was concerned about reintegration, fearing that elephants might become too dependent on their human "keepers" to return to the wild. Then I was so impressed by their reintegration process...how "keepers" assisted with that. I am donating right now!

After reading your excellent article, I feel like living in a neighborhood of elephants could not only be educational but fun!

Thank you Dorothy! Your article well describes this fantastic organization. We visited the Nursery in 2004, and wish so much we could return, but fostering Malkia and Kiko helps keep us connected.

Hi Linda, just wanted you to know the article was written by Barbara Moritsch, she and I were on the same trip last year in October, I just shared it because it's such a great article.

Happy to hear you also sponsor Kiko and MalKia was able to see Kiko when we were there.