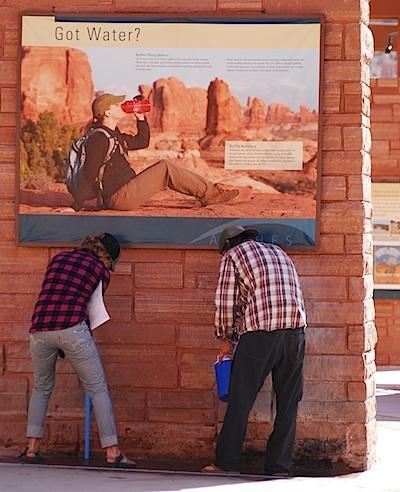

While nearly two dozen units of the National Park System have moved to ban disposable plastic water bottles and installed water filling stations, some members of Congress are still trying to overturn the ban/Kurt Repanshek file photo

A sidenote to the omnibus appropriations bill that is keeping the federal government running through September contains a single sentence that directs the National Park Service to lift its ban on the sale of disposable water bottles in parks. However, it's not legally binding.

The battle over bottled water dates to December 2011, when then-National Park Service Director Jon Jarvis gave park superintendents the option to impose a ban in a move to reduce litter in the parks and waste in landfills. Since then, at least 22 parks have banned their sale, and installed water stations for visitors to refill their reusable bottles and hydration packs.

But the move was never popular with the bottled water industry, and their lobbyists found allies in Congress to push back against the Park Service ban. Indeed, even before Director Jarvis agreed to a ban, the Park Service's commitment to a green environment was partially derailed when Coca Cola in November 2011 raised concerns over plans to ban disposable water bottles at Grand Canyon National Park with the National Park Foundation and Director Jarvis, who initially blocked the ban.

The bottle ban had been in the works for some time. In anticipation of it, Grand Canyon crews early in 2011 installed nine free water stations throughout the park at a cost of more than $300,000, according to calculations made at the time by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility. Six were installed on the South Rim, three on the North Rim.

In coming around to agree to a ban of disposable plastic water bottles, Director Jarvis cited the Park Service's Green Parks Plan, which had a goal of reducing waste in the parks, in part by offering water bottle refilling stations in at least 75 percent of park visitor centers by 2016, the year the agency marks its centennial. (Note: The NPS failed to reach that goal.)

As for banning the sale of disposable plastic bottles, the director outlined three steps superintendents must take to implement a ban: "Complete a rigorous impact analysis including an assessment of the effects on visitor health and safety, submit a request in writing to their regional director, and receive the approval of their regional director."

In his correspondence to the field, Director Jarvis touched on the "symbolism" of banning the bottles from national parks, but also noted the potential consequences of such a move.

"Banning the sale of water bottles in national parks has great symbolism, but runs counter to our healthy food initiative as it eliminates the healthiest choice for bottled drinks, leaving sugary drinks as a primary alternative," he wrote. "A ban could pose challenges for diabetics and others with health issues who come to a park expecting bottled water to be readily available.

"For parks without access to running water, filling stations for reusable bottles are impractical. A ban could affect visitor safety; proper hydration is key to planning a safe two-hour hike or a multi-day backcountry excursion. Even reasonably priced reusable water bottles may be out of reach for some visitors, especially those with large families.

"For these reasons, the National Park Service will implement a disposable plastic water bottle recycling and reduction policy, with an option to eliminate sales on a park-by-park basis following an extensive review and with the prior approval of the regional director."

Since that directive went out, there have been occasional moves to force the Park Service to lift the ban.

Early in 2013 the bottled water industry pushed back against the ban, saying it would encourage visitors to turn to unhealthy alternatives to quench their thirsts. According to the International Bottled Water Association, research shows that in the absence of bottled water products, "63 percent of people will choose soda or another sugared drink – not tap water."

In 2015, the House of Representatives approved an amendment to overturn the ban, but then the bill it was attached to, the House Interior Appropriations bill, was pulled back due to a fight over whether Confederate flags could be displayed at national cemeteries. The Bottled Water Association at the time said the House's move to overturn the ban "is a vote for public health and safety."

Then last year the funding bill for the Interior Department drafted by the House contained language that would have blocked the Park Service from using its budget to enforce the bottle ban.

And now this year, in a report that accompanied the omnibus appropriations bill, a note directed the Park Service to put a hold on the ban.

Bottled Water.-The Committees note continued expressions of concern relating to a bottled water ban implemented under Policy Memorandum 11-03. The report provided to the Committees in April 2016, in response to a directive in the explanatory statement accompanying Division G of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2016, did not provide sufficient data to justify the Service' s actions. The Committees understand that the Service plans to reconsider this policy and therefore directs the incoming National Park Service Director to review Policy Memorandum 11-03 and to report to the Committees on the results of this evaluation. Accordingly, the Committees direct the Service to suspend further implementation of Policy Memorandum 11-03 and urge the Service to examine opportunities to partner with non-govemmental entities in developing a comprehensive program that uniformly addresses plastic waste recycling system-wide.

Technically, though, since that language was contained in the report and not the actual legislation, it's not binding on the Park Service to follow it. That said, when a new director for the Park Service is appointed, he/she is expected to review the policy, according to agency spokesman Tom Crosson.

Comments

I am saying the numbers aren't credible. Whether it is because they were made up or generated using faulty data or methodology or selectively manipulated or the result of other simultaneous initiatives, I don't know. Do you believe that 20% (or more when you account for substitution) of the volume of waste at GCNP came from NPS water bottle sales? Is that credible to you? Is it credible that 20% of GCNP's waste stream was plastic bottles sold by the NPS and it was only 3% at Zion? Is it a true picture of the effect of the ban when data for 12 of the 22 parks wasn't presented? Quoting Mark Twain ""There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics."

George- do you believe 20% of GCNP's waster came from water bottles sold in the NPS stores? Is that credible to you? And if so, why is Zion only 3%?

EC, when it comes to Zion and Grand Canyon, I think one thing to keep in mind is that in Zion there's only one lodge and two campgrounds in Zion Canyon, while at Grand Canyon there are six lodges and a couple campgrounds, as well as a grocery store, so you should expect more trash at Grand Canyon than Zion. And in 2015, which the waste numbers were from, I believe, Zion had 3.6 million visitors, and Grand Canyon 5.5 million.

At the end of the day, while you can argue how accurate the numbers are, I don't think you can say the ban "accomplishes nothing."

Kurt, we are talking % changes. Absolute size doesn't matter although the greater number of lodges and campground at GCNP would suggest bottle water would be a lower, not higher component of the trash.

But hey, lets say the numbers are right. So what? What is the benefit?

Oh for crying out loud, no wonder nobody else wants to try commenting on these articles with their own opinions! They are all afraid they will get their heads bitten off by at least one commenter who insists on having the last damned word and believes that anything having to do with saving the environment, no matter how small, is a waste of time and an indication that the liberal Snowflakes are all at work trying to ruin America. I'm pretty tired of this, and I imagine others are, as well.

Rebecca, respectfully, I would submit I haven't bitten anyone's head off but rather am attempting a logical discussion of the issue. I didn't use the words "liberal", "snowflakes" or anything else implying the ruin of America. If you would care to submit how the bottle ban is of any material benefit to the parks or the environment I would be happy to listen to your arguments and consider them. At this point, I see the bottle ban has merely a symbolic gesture with no real postive impacts and several potentially negative ones.

Yup. It's those pesky plastic water bottles destroying our national parks. And let's not get started on the plastic straws! I beg to disagree, but the link below remains my reading of the problem. If we won't ban this--and all of the infrastructure, favoritism, and kowtowing to Industrial Tourism it requires, why are we jumping on EC for defending plastic bottles? I just thought I would ask.

http://image.trucktrend.com/f/65476871+re0+ar0+st0/grand-teton-national-...

Sigh. I rest my case. And I'm probably not the only one who feels this way. My opinion, regardless of whose links to the "truth" are posted to try and prove me wrong, is that I truly believe this water bottle ban has done some good, with fewer plastic bottles littering the parks. Alfred Runte, it's much like the article you wrote about bringing back mass transportation to the parks. It's going to take a change in the mindset of our throwaway, wasteful, litter-prone society. It will take time, and trying to get visitors to bring their own water bottles is a start. People seem to be less prone to tossing aside their own logo-du-jour-emblazoned water bottles they packed for refill than a bottle of water they purchased at the local mini-mart or park grocery store. Of course, nothing is perfect, but this ban is a start toward changing that mindset and keeping our national parks, national monuments and national seashores less littered with tossed-aside bottles that not only look shameful when seen in an otherwise pristine landscape, but also can do damage to the wildlife. Anything is better than nothing. "Jumping on EC", Alfred? Really?? I'm actually pretty tame considering some of the more contentious comments I have seen on other articles (contentious enough, I might add, to keep other Traveler readers from wanting to post their own opinions).