National parks are far from one-dimensional. They hold history, beauty, and the natural world in all the nooks and crannies of their landscapes. Old-growth forests, canyons that streams and rivers have gnawed into the earth, colorful coral reefs, expansive lakes, and some of the first vestiges of human encounters with nature all are contained within the parks. This great diversity and intersections of nature are what draws QT Luong again and again into the National Park System with his cameras.

It was 2002 when the landscape photographer first completed a journey through all of the 58 "national parks" that existed at the time, an achievement no other large format photographer could claim. This feat was recognized by Ken Burns and Dayton Duncan in their landmark documentary, The National Parks: America's Best Idea. With parks scattered across half the globe, from National Park of American Samoa in the Pacific to Gates of Arctic National Park and Preserve near the roof of Alaska and Virgin Islands National Park in the Caribbean, it would have been easy, and far less expensive, for Luong to celebrate the National Park Service Centennial this year with a new book of photographs pulled from his archives from his earlier adventures through the park system.

But he didn't.

"I revisited almost all the parks for this book project. I am currently two parks away from completing a second round of 59 park visits," he said last week in an email. "In the first round, I was mostly trying to create a few representative iconic large format shots. For the book project, and the second round of visits, I tried to photograph each significant area of each national park. For example: the five islands that make up Channel Islands National Park, the three islands that make up National Park of American Samoa, the three main keys of Dry Tortugas National Park, the five districts in Canyonlands National Park, the three units of Theodore Roosevelt National Park, including Elkhorn Ranch."

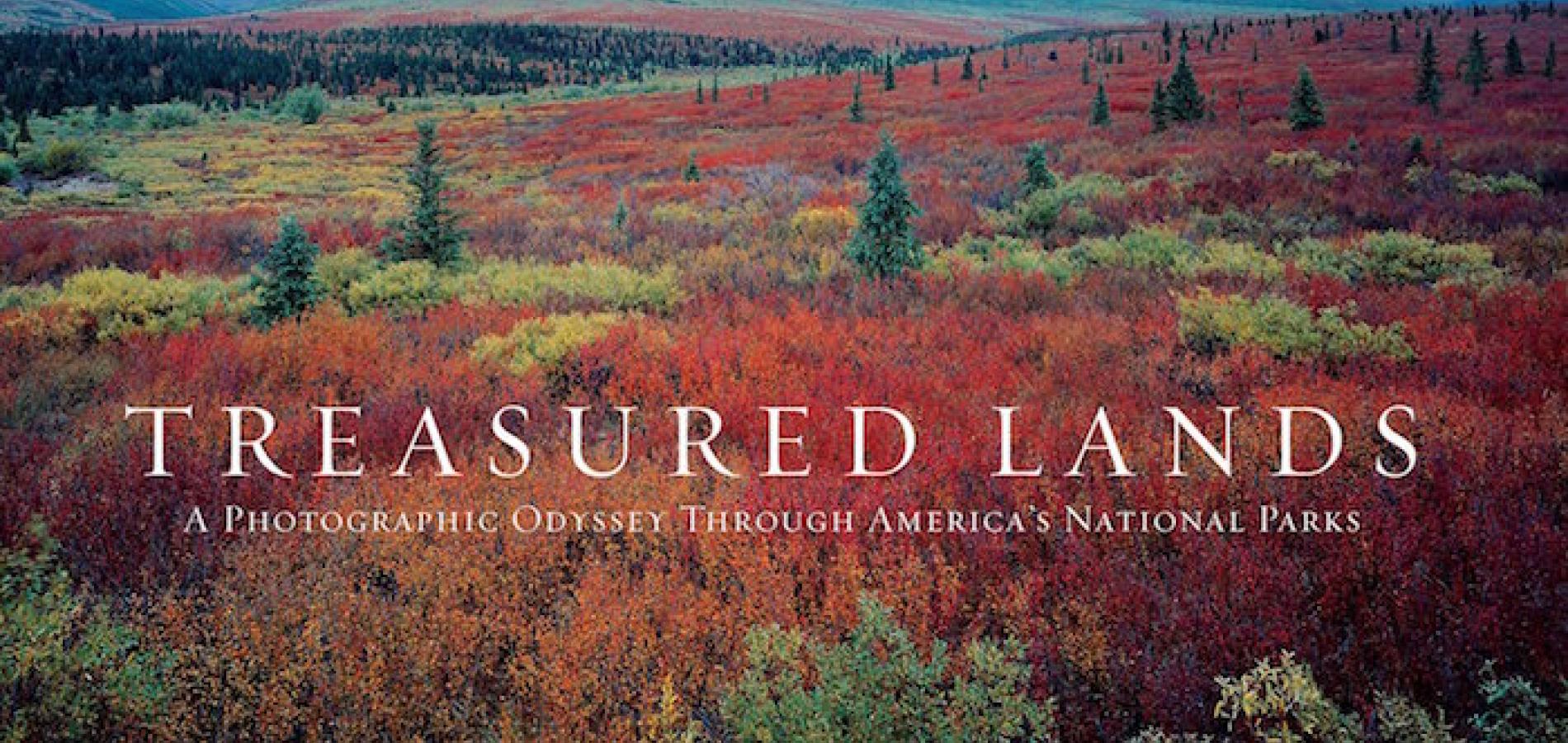

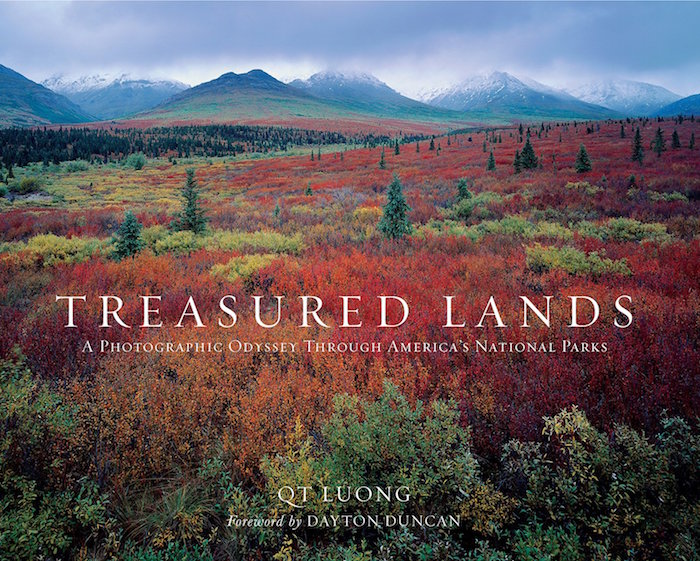

The result is a book, Treasured Lands: A Photographic Odyssey Through America's National Parks, that is impressive not only by its weight -- roughly nine pounds -- but in its expansiveness and the heights, literally, that Luong reached with his 70 or so pounds of camera gear. Page 361 of the book attests to that latter comment, as he stood, at the climax of a solo trek, atop 20,310-foot-high Denali in the core of Denali National Park and Preserve to capture a party of climbers on a ridge leading to the summit.

Repeat trips to parks, as any photographer appreciates, are necessary due to the whims and vagaries of the weather and wildlife. But they are key to success, as Luong's virtually cloudless image of Wonder Lake with a half-moon rising over snow-frocked Denali in the background attests.

Long hours in the field can lead to boredom when you're holed up in a tent waiting for the weather to break or hoping for a band of elk or some other wildlife to appear in your viewfinder. And it can place you in precarious, and potentially dangerous, positions.

"I was stranded, or almost stranded in a number of occasions: flat battery in winter in Arches, had a flat tire with a borrowed car on Mount Washington in Great Basin, almost didn't find my car at Ibex Dunes in Death Valley, ran out of gas in middle of a lake in Voyageurs," he said.

But that time spent can be rewarded handsomely. My own visits to the Racetrack in Death Valley National Park have revealed few of the iconic trails left by rocks inching their way across the playa, yet Luong treats us to an early morning, blue-sky image with no less than two dozen rocks and trails with abrupt turns on the tawny playa. His use of lights to illuminate the windows of a granary within the Inner Gorge of Grand Canyon National Park at dusk produced a striking image. In a slot canyon in Zion National Park his camera captured two owlets on a log. At Hot Springs National Park in Arkansas he pointed his lense upward ... to capture the stained glass ceiling in the Men's Bath Hall of the Fordyce Bathhouse.

We all have our own reasons for visiting the parks. To see Old Faithful erupt. To gaze at the sunrise through Mesa Arch in Canyonlands National Park. To rise in the predawn darkness so we can stand atop Cadillac Mountain in Acadia National Park to be one of the first in the country to see the sunrise. To add to our birding life-list on the Anhinga Trail in Everglades National Park. To marvel at the snout of a glacier in Mount Rainier National Park. To be surrounded by colorful schools of blue tangs while snorkeling the reefs of Virgin Islands National Park. The reasons can be endless. And so it is with Luong in his photographic endeavors.

"I produced many images of the national parks because of the encyclopedic nature of the project," he noted. "Diversity as a whole, and within each park is what causes my fascination with those places. Only a project as comprehensive as the work I've been doing can try to do justice to that diversity."

With that answer in mind, perhaps this book should be viewed as only the most recent chapter in Luong's ongoing odyssey through the National Park System. Dayton Duncan used just that word, "odyssey," in his foreword to Treasured Lands.

"This book is his. It is the culimination of his own odyssey to do what I don't believe anyone else has done to date: chronical America's national parks -- every one of them, in considerable detail, using a large-format camera for the iconic shots, in an era of digital images taken from devices you can carry in your pocket," he wrote. "It is a chronicle of firsts and lasts -- it is the first time all 59 parks have been photographed with a large format-camera, and likely the last, as the world embraces digital. It will be a benchmark for future park lovers and historians, and ranks of his storied predecessors."

Complementing the wondrous images are words that provide not only some history on each of the 59 parks, but also Luong's personal thoughts of many of the locations and, in some cases, the efforts he took to get a particular shot.

"Even when the reef is at a shallow depth, I've found scuba diving to be much more conducive to underwater photography than snorkeling," he wrote in explaining how he got images of reefs at Biscayne National Park. "Scuba diving enables you to go deep, so you absolutely need a strobe. I used one to light up the fish and coral because at depth everything looks blue otherwise."

Treasured Lands is a book that celebrates the National Park Service centennial, but it goes much beyond that anniversary. It captures the 59 "national parks" in their various moods in all seasons of the year, and is certain to lead you to add mightily to your to-do list in the parks.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places