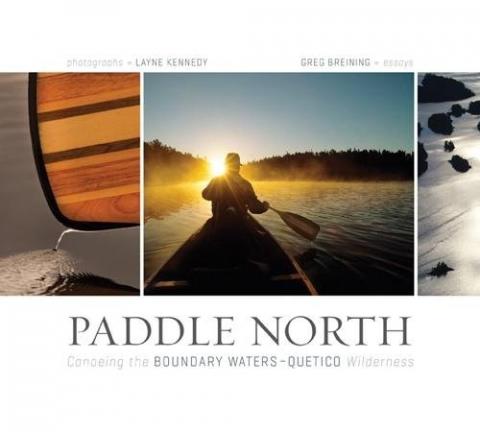

If you prefer the steady dip of a paddle over a footstep down a path, a new book about canoeing from Greg Breining is a book of dreams.

When last we took one of Mr. Breining's books in hand, he took us on a journey to Yellowstone National Park to provide us with insights into the "super volcano" at sleep beneath the park.

In that review we noted that the author approaches geology in a comfortable style that doesn't require you to have passed Geology 101. Indeed, Mr. Breining's book neither required that you have a PhD nor talked down to you. Rather, he simply went about providing answers to questions in a way that can be readily grasped.

Mr. Breining's latest effort -- Paddle North, Canoeing the Boundary Waters-Quetico Wilderness -- comes across much the same, but its subject -- paddling the big lakes and narrow streams of that area -- allows for more personal musings.

Alone on our own tiny island, my wife, Susan, and I watched the sun set on Beaverhouse Lake. A sliver moon dressed the silhouette of a granite island draped in spruce. A loon called, the sound echoing off the far shore and dying somewhere in the distance. We sat on a long outcrop, gnarlier and broader than a whale, where only lichens, mosses, and tufts of grass found a foothold.

People call this canoe country, the Boundary Waters, the Quetico -- Superior. It is a vast tangle of rock-ribbed waterways that sits on the border between Minnesota and Ontario. Beaverhouse Lake lies in Canada's Quetico Provincial Park, but we could as easily be watching the sun set in Minnesota's Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness south of the border. Or just to the west in Voyageurs National Park.

He also delves into the history of canoe making, ranging from the Ojibwe craftsmen who fashioned "long-nose" canoes to Joe Seliga of Ely, Minnesota, the late Bill Hafeman, a skillful creator of bark canoes, to Wenonah canoe founder Mike Cichanowski and Erik Simula, who continues to make bark canoes at Grand Portage National Monument.

And Mr. Breining examines the evolution, if you want to call it that, from paper maps to Global Positioning System units that place the landscape in the palm of your hand.

When I first used a GPS to navigate, I realized that in subtle ways it breaks our ties with the landscape. Instead, we have a relationship with the heavens, in the form of satellite signals. The GPS draws your map for you. In theory you could navigate a route without looking up at the land at all -- just down at the screen as the device consults with the sky. GPS encourages a kind of nearsightedness. You don't have to see where you are to know where you are. And so, as helpful and accurate as they are, I prefer not to use them.

But the joy and wonder of this book is found within the narrative Mr. Breining weaves as he takes in the landscape his canoe glides through, a narrative that shows he is surely as deft with word-smithing as he must be with paddling.

A trip through canoe country begins as a map -- first in the hand, and then in the mind. With the crinkle and scratch of waterproofed paper, a landscape unrolls -- spots of blue and squiggles, dotted lines, and concentric gray contours.

With experience we're able to translate this sheet of paper into a land of lakes, streams and rivers, portages, hills and valleys. It is exciting to see the landscape unfold and to imagine the opportunities for travel and exploration.

Some say that women and men navigate differently, that women follow landmarks and men construct maps. My wife gets impatient when I bury my nose in a map as we travel. We'll get there, she says. We're not lost yet. She is navigating by landmarks, while I'm busy trying to assemble a map in my mind. When I'm caught by surprise, when something appears or fails to appear, as I expect, I must reconstruct my map.

And this narrative also shows that the author remains as attached to the geology he's traversing as much as he was when he wrote Super Volcano, the Ticking Time Bomb Beneath Yellowstone National Park.

You hear the poetry of geology in their names: Gunflint Lake, Red Rock Lake. Iron, Copper. Boulder, Cliff. Magnetic Lake, Gneiss Lake. Granite and Jasper (actually two, one on either side of the border).

An early map labeled this area, for want of details, Land of Rock and Water. Indeed, it is hard to picture one without the other. The reflection of a cliff in a mirror-calm lake. A stream plunging over a jumble of boulders. A sloping ledge pointing toward deep water. Bedrock gliding slowly beneath the canoe. Rock is never more than inches away.

Bedrock is the earth laid bare to the bones. It speaks to our essential nature. It is constant and enduring. Rock of ages. The earth abideth forever. Beneath the surface, rock looks as young as the day it was born.

The rock of canoe country is, literally, the foundation of the continent. Most of the greenstones, granites, schists -- various igneous and metamorphosed rock -- formed between one and nearly three billion years ago. And there they sat while the earth's geologic fireworks shifted to other areas -- as India jammed into Asia, shoving up the Himalayas; as the Pacific plate crashed into the West of this hemisphere, creating the continent's best ski resorts. Meanwhile the core of the North American continent, the Laurentian or Canadian Shield, canoe country, sat in dull constancy, until Ice Age glaciers, Johnny-come-latlies in the geologic scheme, bulldozed earth, cracked off chunks of bedrock, and piled boulders in heaped moraines.

Rock determines the ruggedness of canoe country. There's little soil in the region to smooth things over, to hide the underlying shape of the strata. Think of a portage trail that scales a pile of boulders or surmounts an outcrop. Or the cliffs rimming the lakes. The land is just as abrupt below water, a fact made clear when I first brought a fish-finder to canoe country. Susan and I dropped jigs a rod length from a cliff. The water went down twenty feet, thirty feet, fifty feet! At various depths schools of fish hunkered next to the wall of stone.

Richly complementing this prose are the wonderful photographs of Layne Kennedy, whose work has graced the pages of National Geographic Traveler, Sports Illustrated, Life, Smithsonian and other publications. Mr. Kennedy offers us aerials of the lakes in the Boundary Waters and Quetico, shots of lining canoes through rocky stretches of streams, of paddlers heavily-laden with portage bags, of wildlife, of wildfires in the backcountry, of starry nights in the backcountry.

This is indeed a book of dreams, for those who dream of paddling.