Sweeping across the landscape below me was a scenery studded with blackened trees like so many prickly toothpicks. The view I had from the large pullout about a half-mile up from the Sulphur Works in Lassen Volcanic National Park in northern California is repeated again and again as you drive the park road north from the Kohm Yah-mah-nee Visitor Center in the park’s southwestern corner. Nearly 70 percent of the park had been engulfed by the 2021 Dixie Fire, and the aftermath remains fresh. It’s a sobering view.

Charred landscape near the Kohm Yah-mah-nee visitor center, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

As you continue north, tall, green trees and forest vegetation thrive on one side of the road while a forest of charred skeletons rises above a denuded forest floor on the other. This beautiful, curvy, park road built between 1925 and 1934 effectively acted as a “built-in firebreak” during the 2021 Dixie Fire.

A park road "built-in firebreak," Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Attributed to power lines, the Dixie Fire started 35 miles southwest of Lassen on July 13, 2021. From outside the park, the fire raced into Lassen's north and northeast sections, entering the southeast corner on August 5. On August 12, a separate fire caused by a lightning strike on Morgan Summit near the park’s Southwest Entrance merged with the Dixie Fire to the northeast. Ultimately, 73,240 acres of the park were impacted, and the fire destroyed or damaged 12 park structures -- including the historic Mount Harkness Fire Lookout -- before finally reaching 100 percent containment on October 26.

Today, parts of the park still remain closed due to post-fire hazards. If you’ve visited recently, you’ll likely have seen warning signs indicating that entry into a burn area is at your own risk. And, of course, there are signs cautioning you to stay on trail. Fire can damage tree root systems and loosens soils as anchoring grasses are burned away, making it easy for fire-weakened and burned trees/branches to topple onto trails, roads, buildings, and unwary hikers. In addition, hiking off trail means the possibility of tripping over hidden snags or twisting an ankle in a hole covered by burned needles and ashy soil. Aside from those hidden dangers, every footstep off trail hinders growth of new vegetation.

Key emergency closures map version 7-15-2022, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS

Removing hazards created by the Dixie Fire is a priority for the park, which has contracted with the Mooretown Rancheria of Maidu Indians of California to remove specifically-marked burned trees that “essentially threaten facilities, whether they be buildings or roads or campgrounds,” according to Superintendent Richardson. Hazard trees from the Dixie Fire "are marked for removal with blue paint dots,” said Kevin Sweeney, the park spokesperson.

I spy with my little eye, a blue dot on a burned tree, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

As this hazard tree removal work progresses, visitors will probably see neatly stacked piles of burned logs during a future visit to Lassen, much like the large stack I noticed along the road near the southwestern entrance. What will become of those logs? That’s up to the contractor, but “they may be used for biomass for energy production, firewood for local communities, or sent to mills if they are still sound,” Sweeney informed me.

A pile of burned hazard trees, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

While the Dixie Fire demonstrated the devastation a wildfire can wreak, fire is really not a bad thing for a forest. Fire enriches the soil with nutrients created from burning forest floor debris (aka fire fuels). A fire’s heat releases pine cone seeds, and stimulates growth in trees like quaking aspen. Fire cleans out a dense forest, allowing sunlight to infiltrate previously shaded areas of the forest floor. Fire creates a diverse, healthy forest ecology offering more available wildlife habitat.

Prescribed Fires

Prior to the Dixie Fire, Lassen’s fire management staff was proactively applying protective measures around the park’s most vulnerable areas of buildings, campgrounds, and trails in the form of prescribed fires, which mimic nature’s wildfires but under controlled conditions. You’ll especially notice this while hiking the Cinder Cone Trail in the northeastern portion of the park, where a series of prescribed fires blackened tree trunk bases and cleared forest floors of underbrush and fallen limb fire fuels. Piles of logs and limbs dot the landscape along the trail as further evidence of forest floor cleanup.

“Prospect Peak [a little under four miles from Butte Lake] is the lightning magnet of the park, and by far has the most lightning strikes and fire starts. That area has been thinned out really well from their prescribed fires,” Superintendent Richardson told me. “If you hike the Cinder Cone Trail, you’ll see big trees with lots of space between them, which makes for the healthiest forest."

A cleared forest floor from prescribed fires near the Cinder Cone Trail, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

“When the Dixie Fire headed north, because of the proactively prescribed fires, the wildfire burned maybe three whole trees, then blew through the forest with minimal damage and the Butte Lake Campground opened like normal [this summer],” he said.

The Butte Lake area of the park is not the only location in which prescribed fires are, will be, or have been utilized to restore forest health. Park managers are using similar prescribed burns to protect unburned forests from huge conflagrations like the Dixie Fire.

Northwest Gateway Project

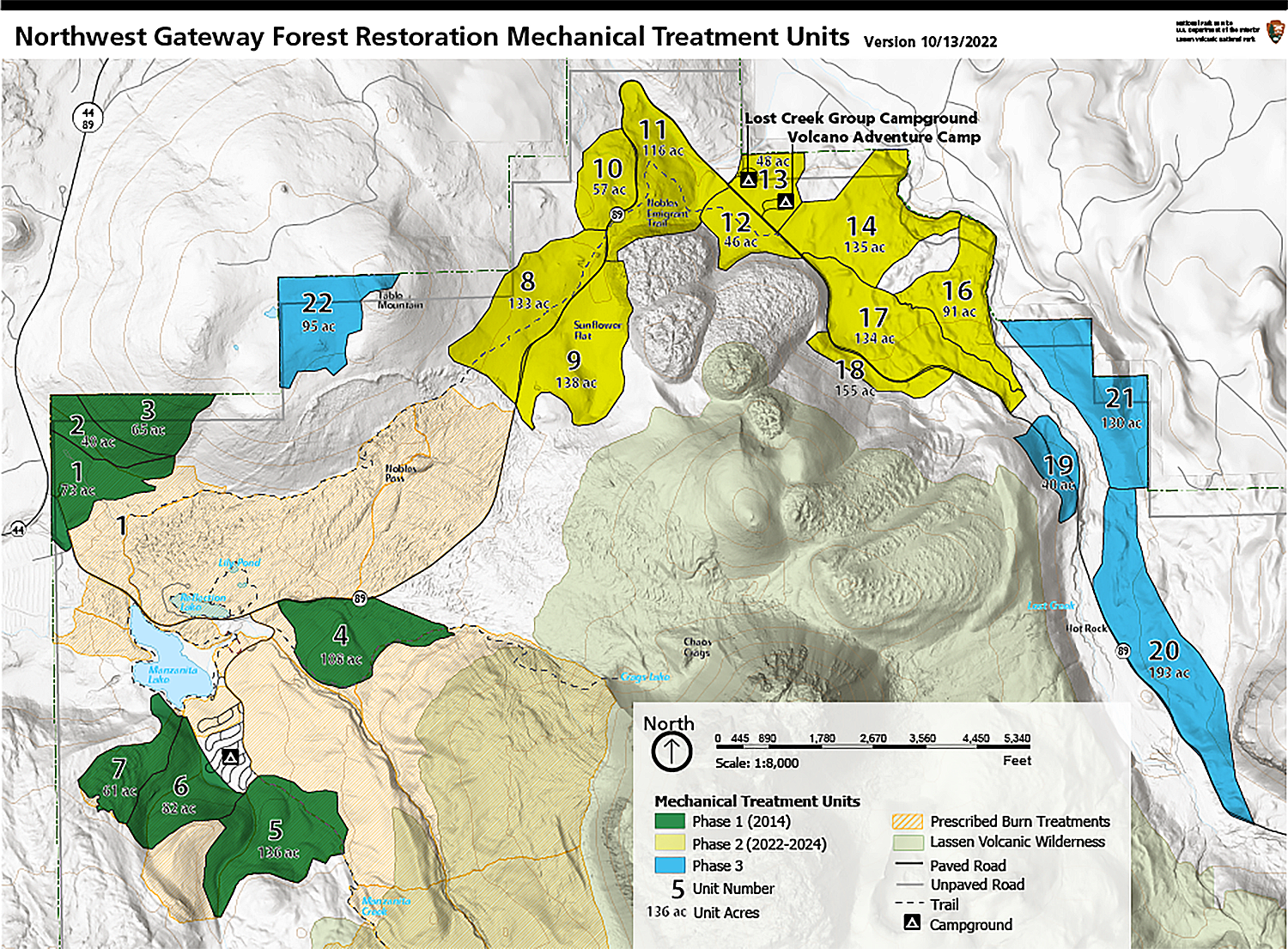

Lassen Volcanic National Park’s northwestern entrance introduces the visitor to the tranquil beauty of Manzanita Lake, the Lost Creek area, and various park facilities. Here, the forest thrives, green and dense - too dense. Well-meaning humans, in their efforts to suppress wildfires, have allowed an environment of shade-tolerant trees and other vegetation to crowd out original wildlife habitat, old growth pines, aspen stands, and understory shrub and grass vegetation. Thanks to drought conditions creating a perfect mix of fire fuels, this forest density increases the risk of far more severe wildfire destruction. Realizing the need “to restore forests to pre-suppression conditions and then maintain forest health by reintroducing natural fire regimes,” park management conceived the Northwest Gateway Project. This phased approach initiated in 2014 utilizes “a two-step process” over a period of years, during which selective mechanical removal of trees is followed by prescribed fires.

On tap for fall 2022: “A contractor will complete mechanical treatment on 124 acres near Lost Creek Group Campground and Volcano Adventure Camp. This work includes removing live understory and ladder fuels … The contractor will rehabilitate all work areas once fuel removal is complete.” Note: ladder fuels are vegetation that allow a fire to climb from the forest floor into the trees.

Northwest Gateway Forest Restoration mechanical treatment units map, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS

How does the contractor know which trees to remove? According to Sweeney, a blue horizontal stripe on trees within the project zone indicates they need to be removed to help achieve forest restoration.

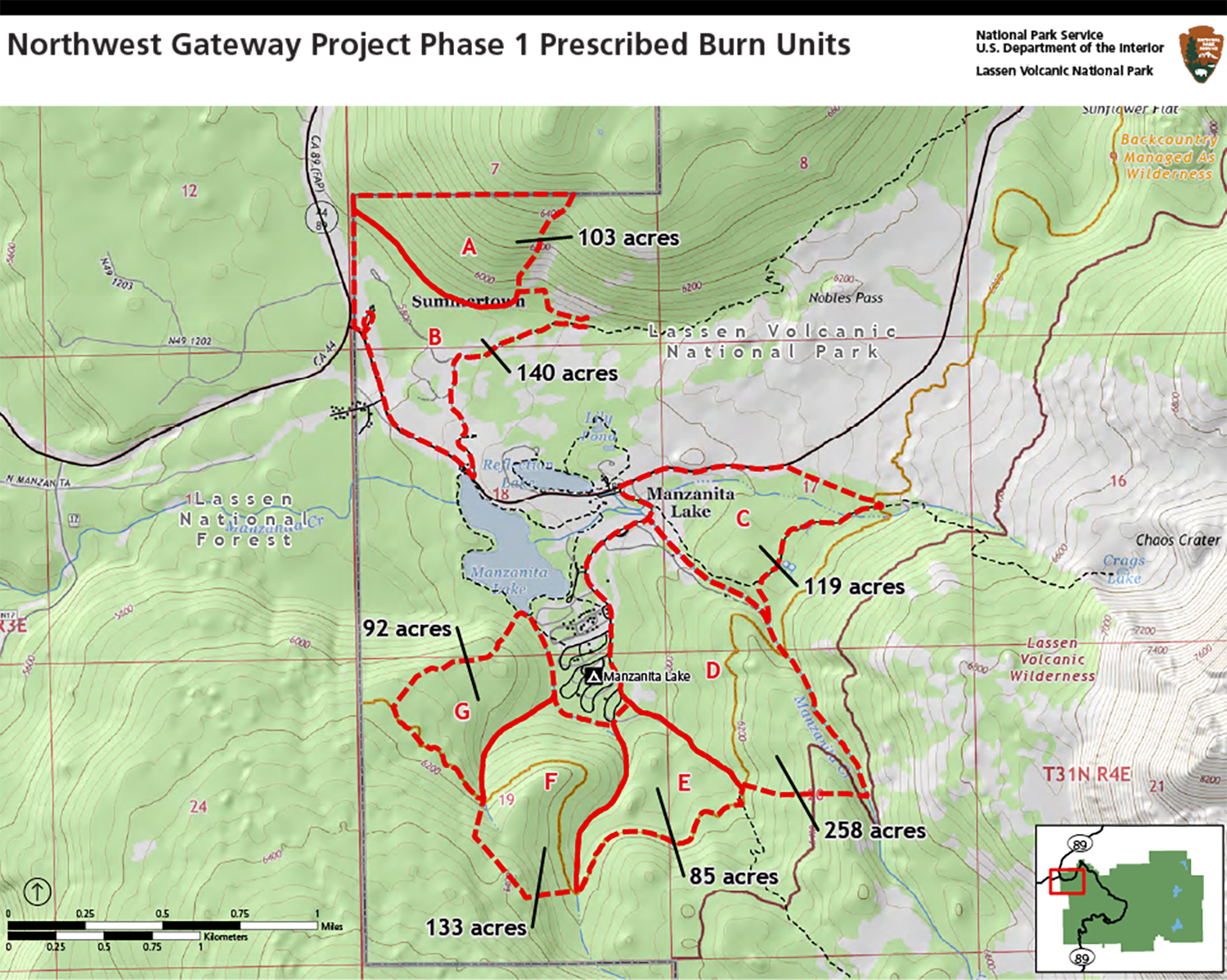

While mechanical tree removal is underway near Lost Creek Group Campground and Volcano Adventure Camp, prescribed fires will be applied to selected locations near Manzanita Lake.

Northwest Gateway Project Phase 1 prescribed burn units map, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS

North Fork Feather River Headwaters Forest Restoration Project

Initiated in 2019 and projected to run through 2024, the North Fork Feather River Headwaters Forest Restoration Project, like the Northwest Gateway Project, employs tree thinning and prescribed fires for fuels reduction on Flatiron Ridge above Warner Valley and along both Warner Valley and Juniper Lake roads.

North Fork Feather River Headwaters Forest Restoration map of the Flatiron unit in the Warner Valley Area, Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS

Whereas the Northwest Gateway Project utilizes mechanical methods for thinning trees, this project, staffed by crews from the Sierra Institute for Community and Environment and American Conservation Experience, applies muscle power to the task of removing fire fuels with cross-cut saws and other hand tools, ensuring "minimal impact to Wilderness areas."

An example of cross-cut saw use on a downed tree / NPS

Visitors to Lassen Volcanic National Park may look at the Dixie Fire burned areas and shake their heads over the devastation of so much acreage. But a closer look of that blackened landscape reveals patches of green already recarpeting the forest floor, a sign of rebirth and a testament to the resilience of the forest landscape, the dedication of firefighters, and the proactive plans of Lassen’s fire management staff.

Sunrise over a renewing landscape, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

References:

https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2021/09/fire-prevention-helps-save...

https://www.nationalparkstraveler.org/2022/05/comeback-trail