An Arborist’s Challenge: Saving John Muir's Giant Sequoia

By Rita Beamish

Martinez, Calif.– The John Muir tree is in serious trouble. The giant sequoia towers 80 feet over the landscape, but its vibe is scrawny — a scarred trunk beneath a skimpy top half, where sparse branches wear scraggly foliage. Gone is the bushy canopy seen in its historic photos. Needles are entirely brown, not a good look for an evergreen’s mantle.

“It’s kind of surprising it’s even lasted this long, being that it’s out of its range,” said Keith Park, the National Park Service arborist and horticulturist who tends the cultural landscape at John Muir National Historic Site. Located in the San Francisco Bay Area city of Martinez, the park is some 150 miles from the giant sequoias’ Sierra Nevada Mountains natural habitat.

Giving the tree a once-over on a recent, sunny, fall day and noting its continued symptoms of a debilitating fungus, Park declared the damage “extreme.”

“I’ve never seen the tree this brown,” he said.

That means the Muir tree, planted some 140 years ago by the famed naturalist and conservationist outside his ranch home, won’t achieve the millennial milestones of its siblings growing high on Sierra slopes, where they live for up to 3,000 years.

Nor will it reach the famously huge girth that makes giant sequoias the world’s largest trees – famously epitomized by the 36-foot diameter of the General Sherman tree in Sequoia National Park.

The Muir tree essentially is a bark-covered billboard affirming from its grassy clearing that even a species as hardy as the giant sequoia is vulnerable to habitat pressures, especially in today’s changing world.

The tree is afflicted by the fungus Botryosphaeria, vulnerable not just because it is far from its native habitat but also because it has endured years of severe California drought and heat, said Park.

“It’s more than a little stressed. It’s a combination of things leading to it not doing well,” the arborist said, adding that, “Another couple years of drought and it will probably be dead.

“I feel personally bad about that.”

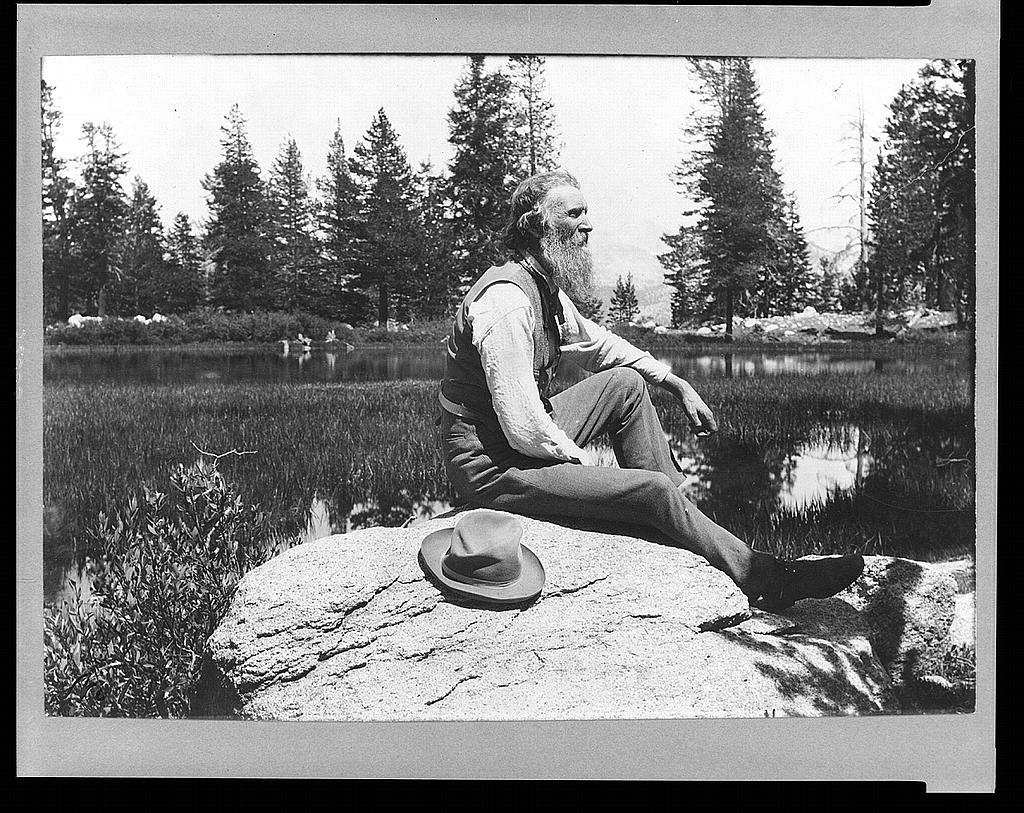

The Strentzel-Muir estate with the sequoia sapling protected within an enclosure/NPS

A Conservation Icon’s Tree

The tree dates to the 1880s when Muir supposedly wrapped the then-sapling in a moist handkerchief and carried it home from one of his Sierra trips. Enchanted by the giant sequoias’ size and majesty, he planted it at a crossroads just down-slope from his family’s grand, Italianate house. Park believes this “very intentional spot” likely reflected Muir’s wish, back before new roadways reoriented the property’s entrance, that “anyone traveling these roads would have to pass by this tree. He wanted to plant it in a place where people will see it.”

Unlike some celebrated giants in the Sierra parks, the tree has no official name; it’s informally called just the Muir tree by park staff. But its connection to Muir himself is central to its importance as a cultural landscape element of the park, which honors the legacy of the national parks advocate.

A 2005 Park Service document, “Cultural Landscape Report for John Muir National Historic Site” stated that the tree “contributes to the significance of the park as a character-defining vegetation feature of the historic period (1849-1914). The growth of the tree conveys the passage of time and adds to the historic character. It is also the most significant example of a seedling plant brought back by Muir from his many travels.”

Park Service Tree Guardians

The fate of the Muir tree is but one challenge that Park and a small cadre of relatively unheralded arborists tackle throughout the National Park System. The agency has just eight full time arborists, along with 92 horticulturists and gardeners, according to a breakdown provided by public affairs specialist Rebecca Roland in the agency’s Natural Resource Stewardship & Science office.

The Muir site is among about 1,000 cultural landscapes the Park Service manages. These locations are recognized for their historic significance and physical authenticity, or their value in continuing cultural practices. “Their significance varies from a historic event, to a historic person, to a historic style of design or method of construction, to a place with the potential to reveal information through archaeology,” the Park Service states.

Arborist Keith Park has worked to improve the health of the Muir tree, which stands 80 feet tall but has been stressed during years of heat and drought away from its natural mountain habitat/Rita Beamish

Cultural landscapes include both natural and constructed features, and reflect human-modified ecosystems, with such features as gardens and terraces. The sites range from urban locations, such as the Muir park, to battlefields like Gettysburg National Military Park to California’s Manzanar National Historic Site, where Japanese-Americans planted gardens and trees during their World War II incarceration.

“Above all, these places demonstrate our continuing need to find our place within environmental and cultural surroundings,” says the Park Service.

In addition to tree and plant specialists, maintenance crews and other park staff also chip in to help maintain the landscapes, Roland noted.

The Park Service runs an 18-month Arborist Training Program to grow the arborists’ ranks. Keith Park, who joined the Park Service 13 years ago, completed the training 2012, and has built on that experience. He maintains the historic landscapes at the Bay Area’s Eugene O’Neil National Historic Site, Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park, and Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial in addition to the Muir site.

A Gardener’s Journey

Before joining the Park Service, Park, having earned a degree in environmental horticulture, learned the intricacies of pruning and shaping fruit trees while working for 10 years in the elaborate gardens of the Filoli mansion on the San Francisco Peninsula.

At the Muir ranch, the trunks of peach trees and other newly planted fruit trees are painted with white latex paint. That’s “essentially a sunscreen” Park explains, protecting against beetles as well as excessive sun that causes lesions on the bark. Trees also are pruned into an open-center, chalice-like shape for optimal sunlight and air flow.

Pear, apple, and apricot orchards, as well as grape vines and olive trees are among other landscape features of the site, along with two historic wells and the flowering garden plants around the ranch home where Muir lived until his death in 1914. Family diaries and writings help ascertain what was on the landscape in the late 1800s and early 1900s for historical accuracy.

“If you have a home that’s historic, people expect to see the look of the time period. I apply that to landscapes, and the shape of a tree,” Park said.

Trees in a peach orchard at John Muir National Historic site are pruned for optimal air flow and sun, and have white latex paint on their trunks and branches to protect from destructive beetles and too much harsh sunlight/Rita Beamish

Arborist work takes Park to other national parks to conduct tree hazard assessment and other consultations. Safety is the top priority, particularly where falling limbs may threaten structures, campers’ tents or visitors below.

“We want the tree, but we don’t want it to be dangerous,” he said. “The balance is in keeping the tree as a resource that looks natural, and making it safe.”

On visits to Channel Islands National Park off the California coast, Park assesses trees for safety and pruning needs; he has pruned eucalyptus trees dating to the 1880s.

In dry, rocky Pinnacles National Park, he stabilizes old valley oaks whose shade is appreciated by visitors but whose limbs can become overladen in heavy acorn-bearing years and can pose a falling hazard.

In Yosemite National Park, he assessed black oak trees where branches threatened structures, and learned of their cultural importance from Indigenous park staff. He recommended gradual pruning to shift weight toward the tree center, while maintaining a natural look.

Park has conducted workshops on preservation horticulture, working with the agency’s Park Cultural Landscape Program. He also works with the National Cemetery Investment Initiative, which is dedicated to historic landscapes at the 14 military cemeteries the Park Service manages. Transferred from the War Department to the Interior Department starting in 1933, they include sites like Soldiers National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Antietam in Maryland, and Yorktown and Fredericksburg in Virgina.

In 2021 Park was recognized with a National Park Service Award for Cultural Resource Stewardship, which noted his collaboration with a Native American forestry crew and park staff to maintain Yosemite’s historic Curry Village apple orchard.

Across his park experiences, one stirs particularly happy memories: “One of the coolest things I’ve ever done,” he said, “was pruning plants on rim of the Grand Canyon. Who gets to do that?”

Sequoias In Trouble

The Muir tree still stands stoically below the knoll topped by Muir’s house. The disease assaulting it is a vascular-wilt fungus known for infecting weak or “stressed out” plants. It clogs their “vascular systems,” preventing transfer of water and nutrients through the tree, Park said. Often fatal when stressed plants are deeply infected, the Botryosphaeria detected in the tree in 2010 has persisted despite park efforts involving irrigation, composting and soil aeration.

The Muir tree sits on a slope where John Muir planted it in the early 1880s, below the house where he lived for the last 24 years of his life/Rita Beamish

Even in their Sierra habitat, giant sequoias are picky about their soil preferences and surrounding ecology. Only about 75 groves exist, all on western slopes and in the 4,000-8,000-foot elevation range. Famous for their longevity, the giants in recent years have taken an unprecedented beating under the interlocking triple threat of drought, bark beetle infestation and voracious California wildfires.

Particularly destructive wildfires in 2020 and 2021 were estimated to have killed 13 to 19 percent of the giant sequoias in the entire Sierra Nevada population, according to the Park Service. That created such alarm that the National Park Service this past fall began a replanting project in parts of Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks. The effort has come under attack by some environmental groups that sued in federal court to try and halt it, alleging the activity is not necessary and violates dictates against human intervention in designated wilderness.

A Tree's Decline

A few years ago, Park climbed the Muir tree and collected cuttings. He sent them to a Michigan group, Archangel Ancient Tree Archive, which focuses on propagating old growth trees, including by cloning them in controlled indoor conditions. The samples were sliced into about 400 smaller cuttings, but just three or four took root when nurtured in the group’s indoor facility, Park recalled. None survived once planted outside.

“Heroic measures” to extend the tree’s life could include injectable fungicides and insecticide, which Park said he’s considering. But ultimately such efforts raise philosophical preservation questions, like: “What is a historic tree worth?” he said. “They are living beings and they only have a finite lifespan. Maybe this tree is at or beyond its life span in this area.”

And ultimately, he notes, “Nothing is going to live forever. That’s the rub with preserving and maintaining historical plants.”

It’s not even known if the tree has passed the point of being able to benefit from chemical injections. But, "it is unlikely such treatments at this stage would take the tree from its present state to one of vigor and longevity,” Park said.

If it died, it would still stand for several years, and ultimately there could be other ways to perpetuate the cultural resource point of view, such as planting another tree or otherwise interpreting the spot, he noted.

Park calls the work of caring for America’s treasured landscapes his dream job. “I feel very lucky to be able to do these things, that I am trusted to do this sensitively. I appreciate that I’ve been able to go to parks and do this kind of work,” he told the Traveler. “It really is a privilege.”

Comments

I've been there many times and seen that tree each and every time.

I guess it's tricky since it might just be a losing battle, especially since it's far from an ideal location for a giant sequoia. That being said, the giant sequoia is apparently a fairly common landscaping tree around the world at lower elevations. However, those are treated as landscaping and if they die they can be replaced. We're holding on to this tree because Muir specifically planted it. But certainly there could be a time when it's a losing battle and it's time to let it go.