Julian England, chief operating officer for the Canadian Rockies Hot Springs (what Parks Canada refers to internally as the Hot Springs Enterprise Unit) is shown at Radium Hot Springs in November/Jennifer Bain

Relaxation doesn’t come naturally to everyone, so when I grudgingly slipped into the steamy, mineral-rich water at Radium Hot Springs, I couldn’t help but think of that deadly day in 1967 when a semi truck hauling gasoline lost control on the steep mountain highway nearby and crashed, killing the driver and spilling more than 7,000 gallons of fuel into the creek that ran beside the hot pool and under the main stone building.

As flames as high as 150 feet swept down Sinclair Creek, a quick-thinking 20-year-old lifeguard named Victor Thygesen moved the eight swimmers there that day to the deep end and then behind a lifeguard shack until the intense heat subsided and they could swim to the shallow end and flee.

Those people miraculously escaped injury. But windows were shattered and the damaged pool had to temporarily close. Rock walls had edged the canyon side of the pool, but Parks Canada wisely redesigned the pool area to hide the creek and hot springs source in a bid to make everything safer.

A view of the renovations to Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park and its "cool pool" in November 2023/Jennifer Bain

When I arrived in British Columbia’s Kootenay National Park during a shoulder season road trip in November, the fabled Radium Hot Springs Aquacourt was once again undergoing renovations. This time the focus was on the “cool pool” along with other upgrades to boost the site’s resilience to flooding and make it safer and more accessible.

On a behind-the-scenes tour, I lingered by a filing cabinet that held all the building plans starting from 1949. A vintage sign waxed poetic about the “many faces” of Radium.

“Although this face has been altered many times since the 1920s, one thing that will never change is the soothing character of the spring’s steamy water,” it read. “That — the heart of Radium Hot Springs — remains unalterable.”

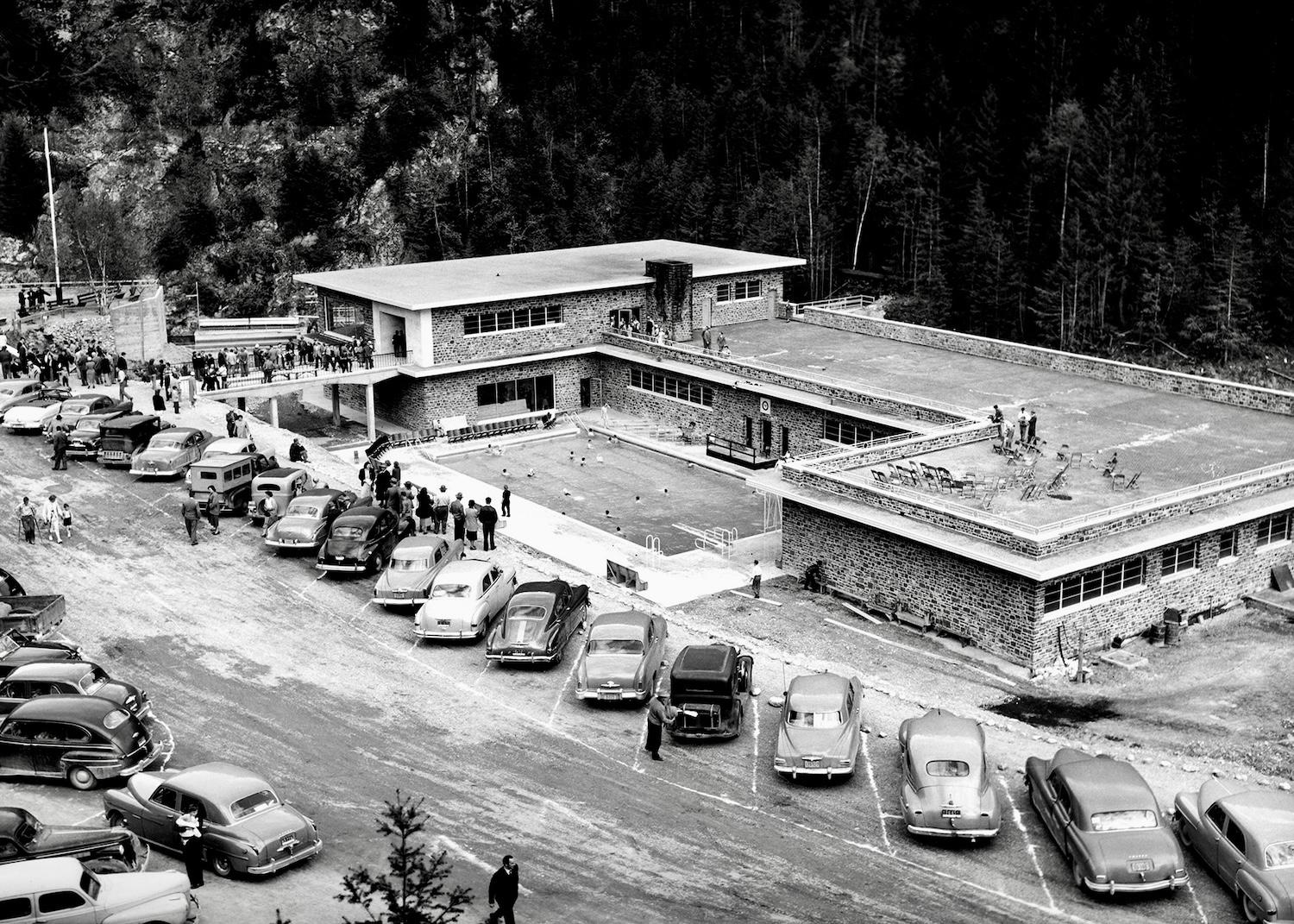

A crowd was on hand for the 1951 opening of the Radium Hot Springs Aquacourt building/Parks Canada

Julian England guided me on that fascinating tour through the bowels of the building. He’s the chief operating officer for what Parks Canada privately calls the Hot Springs Enterprise Unit but publicly calls the Canadian Rockies Hot Springs. He manages Radium plus two spots in Alberta — Banff Upper Hot Springs in Banff National Park and Miette Hot Springs in Jasper National Park.

“I think the hot pools are important because they allow people to easily connect with the park,” England told me. “It’s an easy way for somebody to connect with the park who may not be able to participate in hikes and get out into nature.”

Then there's the bonus that on the environmental front, the hot springs draw high visitation but only cause minimal erosion thanks to hardened surfaces.

Writer Jennifer Bain rented a retro swimsuit at Banff Upper Hot Springs in Banff National Park in March 2023. She rented another at Radium Hot Springs in Kootenay National Park in November 2023. Parks Canada has them made and they area modelled after a design from the 1920s/Photo courtesy of Linda Barnard

It's a little-known fact that Canada’s national park system began because of thermal waters.

In Alberta, a small mountain cave with natural hot springs — long treasured by Indigenous nations — was eventually discovered by Canadian Pacific Railway workers in 1883. The area was first protected as Hot Springs Reserve and evolved into Banff National Park in 1885. While you can now only look at these waters (home to an endangered snail) at Cave and Basin National Historic Site, you can soak nearby in Banff Upper Hot Springs, where heated municipal water sometimes replaces thermal water during low-flow times in winter.

Like Banff, Radium is open 365 days a year (yes, even on Christmas) on a first come, first served basis. Radium is also the largest of the three sites. For $2 Canadian at Banff in March and Radium in November, I rented a unisex historic bathing suit modelled after those worn in the 1920s. The suits were originally knit wool, but now they're polyester knit. It’s getting harder for Parks Canada to find a company to make them, so lets hope they don't disappear.

Opened in 1951, the modernist Radium Hot Springs Aquacourt is a low-slung building with horizontal lines/Jennifer Bain

What stood out for me at Radium, though, was the modernist concrete and stone building designed by architect Ernest T. Brown and built between 1949 and 1951.

Sitting in the basin of a gorge, the Radium Hot Springs Aquacourt is a Classified Federal Heritage Building — that’s the same status as the Parliament Hill Complex in Ottawa where four Gothic Revival pavilions make up the Parliament Buildings.

The Aquacourt was the first major post-war building project in the western parks and played a key role in spa development in Canada’s national parks. It heralded a shift away from the rustic aesthetic that had dominated national park design philosophy. Its modernist design was influenced by the International Style of architecture, with asymmetrical but visually balanced cube massing, a U-shaped symmetrical plan, strong horizontal lines and flat roofs. There’s a basement, main level, penthouse and roof terrace plus hot and cool pools.

The "cool pool" at Radium Hot Springs is getting some much-needed renovations/Jennifer Bain

In the hallway between changerooms, I read punchy interpretive signs about the site's history. Hot mineral water has long flowed from the canyon walls into Sinclair Creek. Indigenous Peoples were the first to soak in what came to be known as sacred, healing water.

In 1841, Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson’s Bay Co., made the first recorded visit to the hot springs, bathing in a pool dug out of the gravel that was big enough for just one person. Trader/explorer James Sinclair followed suit a few weeks later while taking a group of Red River settlers to Oregon, and the local canyon bears his name.

Things really got going in 1890, when Englishman Roland Stuart bought the springs and planned to bottle the water as a tonic. He built a concrete bathing pool, log bathhouse, small store and caretaker’s home in 1914. He renamed the site Radium Hot Springs after researchers from McGill University identified trace amounts of radon in the water. But in 1922, Stuart's property was expropriated to make the springs part of the newly created Kootenay National Park.

Just south of Radium Hot Springs is this spectacular stretch of highway at Sinclair Canyon/Jennifer Bain

“The growing Canadian middle class enjoyed motoring along the new Kootenay Parkway to visit Radium Hot Springs and the Columbia Valley,” an interpretive sign reminisces.

A bathhouse was built in 1927 and burned down in 1949. Two years later, more than 1,000 people attended the grand opening of the Aquacourt on May 19, 1951. In 1968, a new hot pool replaced the original 1914 pool after the fuel truck crash.

Since then, there have been waves of renovations. What started as spring water captured in rudimentary pools made of gravel, logs and mud is now a cherished complex that features the best water treatment available. It is a recreational space that's loved by the community as well as visitors from around the world. When the Winter Olympics brought the torch relay to Kootenay on Jan. 22, 2010, the first of 12 torchbearers swam a few lengths of the pool before passing the flame to the next runner.

Parks Canada staff are specially trained to handle the chlorine needed for Radium Hot Springs/Jennifer Bain

On the two days that I visited Radium — sleeping at the Gateway motel and getting my turmeric latte fix at the Big Horn Café in the village of Radium Hot Springs — the hot pool water was 102F. That's too high for my comfort and I honestly only spent a few minutes in the soothing waters. I soon learned that each of the three Rocky Mountain hot springs has its own blend of minerals, gases and temperature.

Signage explains that the water here travels deep into the earth and returns to the surface with more than 700 milligrams of minerals per litre at a rate of 1,800 litres (396 gallons) per minute. The water is 114F at the source but then chlorinated and cooled to a more comfortable temperature as it enters the hot pool. Parks Canada says the top five minerals found in Radium's odorless hot water are sulphate, calcium, bicarbonate, silica and magnesium.

As for that trace amount of radon, the government agency promises "the amount of radioactivity is harmless and is much less than that given off by an ordinatry watch dial."

There is always laundry for Parks Canada staff to do at Radium Hot Springs, since you can rent a bathing suit and towel/Jennifer Bain

I'll admit that England lost me as we explored the basement and he detailed what all the machines and pipes do in the water's journey from creek to pool. But if you've wondered why you need to shower before getting in a public pool, it's to reduce the amount of chlorine needed to kill germs. There's a machine that senses what chlorine level is needed. Radium visitors are warned that sprays, including spray-on sunscreen, will remove the pool's epoxy paint and damage swimsuits.

Lifeguards help with laundry (all those rental towels and bathing suits) during mandatory breaks from their main duties. Free swimsuit dryers in the changerooms are popular with guests. Less popular was the time between 2008 and 2012 when Parks Canada considered privatizing the hot springs. Also unpopular is the fact that Parks Canada finally got ministerial approval to boost fees this year. They had been essentially frozen since 2004, and so leapt from $8 to $16.50 (Canadian) for adults, although there are deals for multiple visits and annual passes. The Aquacourt is the only pool in the nearby town and the cool pool is used for swim lessons and swim club races.

Radium Hot Springs draws some 280,000 visitors a year, Upper Banff Hot Springs about 480,000, and the seasonal, somewhat remote, Miette Hot Springs another 200,000. While the federal government pitched in infrastructure money for Radium's latest renovations, the hot springs use visitor fees to cover their operating costs. England dreams of having the budget to one day "be able to see the stars from the hot pool," something that would require expensive new lighting systems.

To cross the highway at Radium Hot Springs, Parks Canada installed a pedestrian underpass that tells the story of wildlife overpasses and underpasses/Jennifer Bain

I thought a lot about England's observation that visiting hot springs gives people who may not hike a way to bond with national parks. Maybe it's also the first step in nudging them to go for a walk. A convenient mountain trail just outside the back of the Aquacourt connects the hot springs to Redstreak Campground. Families like to tire their kids out on the trail, treat them to a dip in the hot springs, and then take them home good and tired.

Kootenay is grizzly bear country and you're not supposed to wander around alone or without bear spray — at least until it's winter and the animals are hibernating — so I welcomed the chance to go for a short, steep stroll with England while there was only a dusting of snow on the ground.

We walked to a large boulder in the forest. On it, a plaque said this was the Place of Silence Peace Park and included a famous quote from Christian theologian Thomas à Kempis. “Keep peace within yourself, then you can also bring peace to others.”

On the slope across from Radium Hot Springs, Parks Canada created this hibernacula (winter den) for Northern rubber boa snakes/Jennifer Bain

Looping back to the Aquacourt, we walked through a pedestrian tunnel to safely cross under the highway to the overflow parking lot. Parks Canada plasters the tunnel with messaging about how it builds similar underpasses, overpasses and fences to help wildlife cross the road.

At the spot where a lodge once stood overlooking the hot springs, England and I talked about how the Sinclair Canyon restoration area now provides important habitat and travel corridors for animals like endangered American badgers and Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep.

I was fascinated by a hibernacula (winter den) for Northern rubber boas, a small, non-venomous snake with a blunt tail and shovel-like snout that has been dubbed the two-headed snake. This nocturnal species at risk lives near the hot springs but is rarely seen. It likes rock piles where it absorbs the warmth of the rocks and hides from predators. Parks Canada constructed the hibernacula by piling logs and rocks in the foundation of what was once the park superintendent’s house.

A Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep walks down the middle of the highway near Radium Hot Springs/Jennifer Bain

It was too cold and dreary for snakes, but we stopped to watch a lone bighorn sheep casually make its way through the restored landscape at a safe distance from the highway.

Then as I drove back to the village and pulled over to photograph Sinclair Canyon, I watched in horror as another lone sheep walked blithely down the center of the winding road. The iconic herd that once numbered 250 has dropped below 120 because speeding drivers hit and kill them.

A wildlife overpass is coming. But until it's built, people are urged to slow down along this treacherous stretch of road that passes the famously soothing waters of the largest and most accessible hot springs in the Rockies.

While You’re In The Area:

After hiking to the top of the Dutch Creek Hoodoos Conservation Area, view the eroded sandstone cliffs from the highway below/Jennifer Bain

When Canadians think of hoodoos — weathered sandstone pillars — they picture the mushroom-shaped ones in Alberta near Drumheller and in Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park. But British Columbia has them, too, in the Dutch Creek Hoodoos Conservation Area at the north end of Columbia Lake near Fairmont Hot Springs. Protected by the Nature Conservancy of Canada, these alien-like cliffs are deposits of gravel, sand and silt left by retreating glaciers and then shaped by thousands of years of wind and rain erosion. A short, looped forest trail takes you to the top of the hoodoos (aka fairy chimneys and earth pyramids). For a better look from below, stop along the Kootenay Highway near the Dutch Creek Bridge.

The hoodoos are about a half hour's drive from the Radium Hot Springs village and near Fairmont Hot Springs Resort, another place to experience thermal waters while exploring the Kootenay Rockies. The resort — which got its start in the early 1900s and isn’t connected to the luxury Fairmont brand — has a small guest pool and large public pool. Don’t miss the Indigenous historical baths on a plateau of tufa rocks. For thousands of years, Indigenous Peoples bathed in the hot springs water here in natural indentations or in small pools they carved or created with stones. They believed in the curative powers of the water. You'll also see one of the first buildings the resort built to make it easier for guests to use the natural rock pools of hot mineral water.

At Fairmont Hot Springs Resort, near one of the first buildings erected to help people bathe in thermal waters, are natural rock pools of hot mineral water first used by Indigenous People/Jennifer Bain