Inside the fabled cave with natural hot springs at Cave and Basin National Historic Site within Banff National Park/Jennifer Bain

For 10,000 years, people from the Stoney Nakoda and other Indigenous nations climbed down rawhide ladders into a small mountain cave to trade, drum, sing, pray and bathe. They believed the natural hot springs water was a gift from the Creator and Mother Earth and used it for blessings and healing.

Then in 1883, three Canadian Pacific Railway workers named Frank McCabe, William McCardell and Tom McCardell smelled sulphur and spotted steam rising from the ground. They descended into the cave on with a tree trunk ladder and, dazzled by the "extravagent shimmering," declared “it was as if one was in a chamber of jewels.”

News of this magical cave set off a chain of events that launched Canada’s national park system.

Cave and Basin National Historic Site is set within a forest in Banff National Park just minutes from the town of Banff/Jennifer Bain

Fast forward to March and I’ve finally come to what’s now called Cave and Basin National Historic Site in Banff National Park. The popular Alberta site draws more than 200,000 visitors a year.

Amar Athwal, a photographer and the Parks Canada team leader for the site, says it’s just “50 steps in and 50 steps out” of the cave, and to hurry and enjoy it during a lull between visitors.

I don’t have to shimmy down any kind of ladder because Parks Canada blasted an entry tunnel in 1886. The dimly lit cave has a low ceiling and smells like rotten eggs from the sulphur. Signs warn to stay on the concrete footpath and out of the water because there are endangered Banff Springs Snails and “unique cultural features” to protect.

It's a challenge to pinpoint flowstones, speleothem (calcite formations) and glacial till without expert guidance, but easy enough to identify the masonry wall and viewing platform. Looking up, I can see the sky through the vent hole that people used to climb in from.

It's 50 steps into the famous, but small, cave and 50 steps back out through a tunnel constructed in 1886/Jennifer Bain

When people wander in and quickly pack the cave, it's time to backtrack to the interpretive exhibits and take a guided tour with Athwal.

Walking through the tunnel into the cave provides "a sense of enchantment," according to the site's 2020 management plan, and helps people discover why this cavern has deep, multi-layered meanings for Indigenous peoples and Parks Canada. Visitors "are struck by the uniqueness of the thermal water environment, its importance to multiple Indigenous nations, and its rich post-contact settler history."

The Cave and Basin site is in the forest on the lower slope of Sulphur Mountain on what Athwal explains is the present-day territories of Treaties 6, 7 and 8, as well as the Métis Homeland. It's important to acknowledge that Indigenous access was fundamentally harmed when their traditional land was taken over by the federal government.

A mural depicts the three railway workers credited with rediscovering the cave and thermal springs/Jennifer Bain

After those three men helping build a railway across Canada stumbled upon the cave, they reported feeling invigorated by the "uniqe bath" in "warm and limpid waters." As William McCardell wrote in Reminiscences of a Pioneer, "the explorers searching for the mythical fountain of youth could have done no better." They built a log shack next to the cave's vent hole to protect their claim as they petitioned the government for the rights to develop the land. It came to be known as Banff's first "hotel." Eventually, the prospectors lost and received settlement money.

On Nov. 25, 1885, when Canada was not even 20 years old, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald set aside 26 square kilometers (10 square miles) of land to protect the thermal springs and called it the Hot Springs Reserve. Two years later, this reserve was vastly expanded and became the core of Canada's first national park, which was later renamed Rocky Mountain Parks and finally Banff.

The move was largely inspired by the spa resort at the Arkansas Hot Springs and Yellowstone National Park, which became a world first when it was established March 1, 1872.

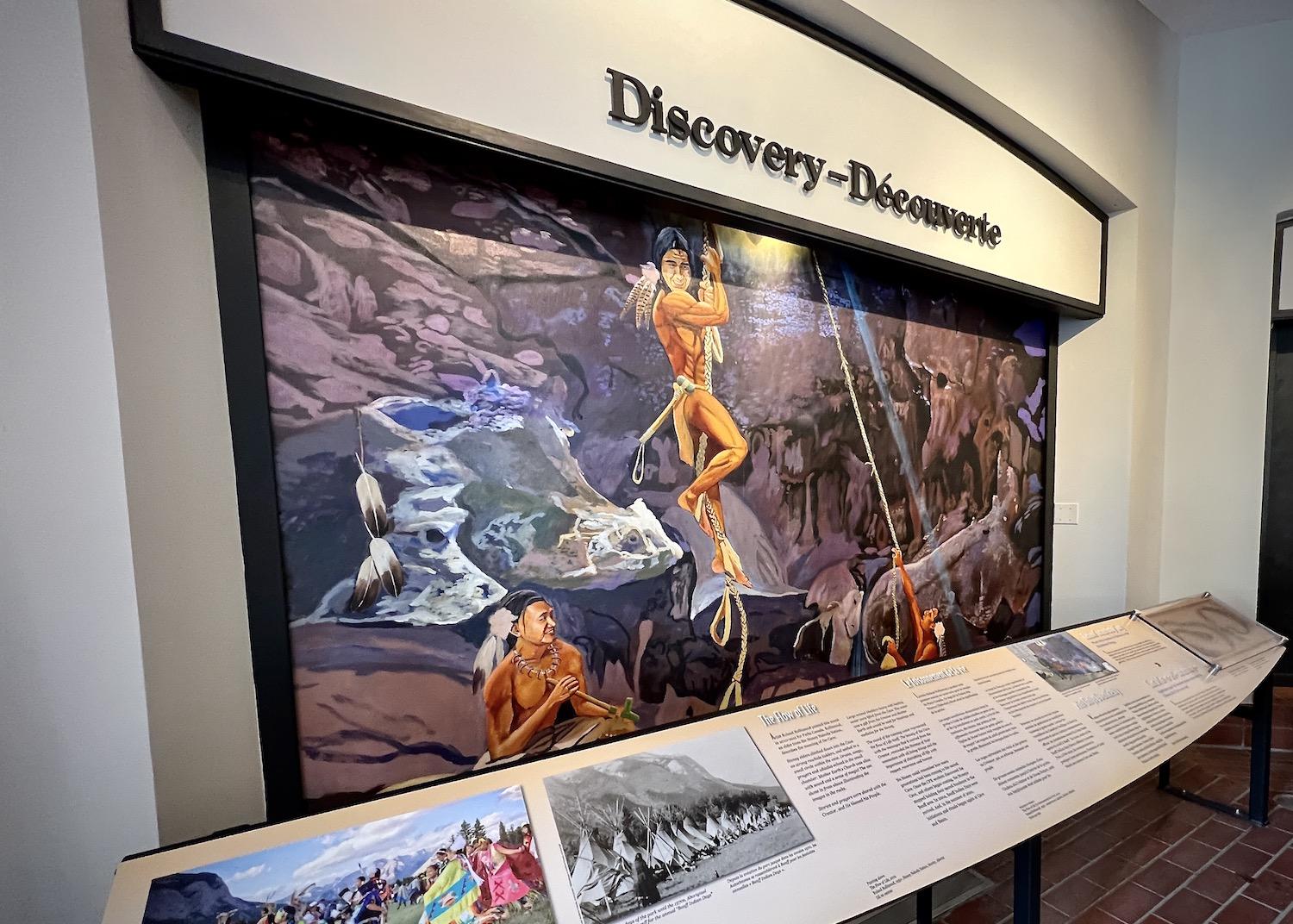

A mural depicts the Indigenous people who have known about the cave and thermal hot springs for thousands of years/Jennifer Bain

The entry tunnel was the first order of business so people could walk, not climb, in. Then the pools were stabilized and two bathhouses and a caretaker’s cottage were built as the first national park buildings. A bathing pavilion and open-air swimming pool were added in 1914.

The pavilion was dazzling, while the pool was the largest of its kind in the country and boasted decks with mountain views. It was made of locally quarried rundlestone and the rustic appearance, with distinctive black and brown hues, became a signature architectural style in Banff.

By 1935, the cave and basin site was a major attraction — “an important place where Canadians could relax and find physical and spiritual renewal by bathing in the curative mineral spring waters and enjoying recreational swimming and sunbathing,” according to Parks Canada.

The Story Hall, beside the entrance to the cave, tells the story of the site and the creation of Canada's national park system/Parks Canada

National historic site status was granted in 1981 to honor the birthplace of Canada’s national park system.

The site is minutes outside the town of Banff and encompasses the cave, original vent hole, archaeological remains of the original hotel near the vent hole, the basin, thermal springs above and below the buildings, bathing pavilion and caretaker’s cottage.

There's now a Welcome Building, gift shop and orientation plaza by the parking lot. The Bathing Pavilion Complex contains the historic Bathing Pavilion building, cave spring pool, basin pool, 2013 Galletly building, and a large outdoor deck used for programs where the swimming pool once stood. The complex houses the Story Hall, which calls itself “a place of connection, a place for conversations about conservation, a place for sharing stories about people and the land.”

The pool is long gone and has been covered up. During my March visit, people curl during a winter festival/Jennifer Bain

Understandably, the site has become many things to many people.

“For numerous Indigenous peoples, Cave and Basin is a sacred place,” the management plan reports. “For Parks Canada, it has high symbolic value as the birthplace of Canada’s national parks. For the local community, it is a place to gather for events and relax with family and friends. For the local business operators, the site is part of the tourism industry framework.”

The day that I visit, curious visitors from far-flung countries are dabbling in curling and hockey during a small winter carnival.

Cave and Basin's promotions officer Skyler Langendoen and team leader Amar Athwal stand by the spot where the cave's vent hole was found, and a shack that became the area's first "hotel" once stood/Jennifer Bain

On tour with Athwal, I read a sign that helps me finally understand non-volcanic hot springs. “This is no ordinary water. Just as hot coffee filtered through ground coffee beans becomes coffee, this stream has filtered through rocks deep in the earth to become warm, mineralized and slightly radioactive — hot springs water.”

In 1906, invalids arrived from all over the world for treatment. By 1918, the sulphur waters were said to help with skin diseases, gout, chronic rheumatism, syphilis, stiff joints, gunshot wounds, and mercury and lead poisoning. By the 1980s, the medical claims were being challenged, but people still believed that hot springs baths helped with muscular problems and relaxation therapy.

Parks Canada's Amar Athwal stands outside at the original steam vent (now protected with a grate) for the cave at Cave and Basin National Historic Site. It's the original access point/Jennifer Bain

It should be pointed out that you can no longer swim here, or even stick your finger in the waters that protect a fragile ecosystem. Instead, you must drive 10 minutes away to the outdoor pool at the Banff Upper Hot Springs, where for $2 you can rent replica 1920s-era swimwear.

Still, there is much to learn and do here. When I stumble into a building with a First World War internment exhibit, I'm confused. Then I learn how some immigrants from countries with which Canada was at war were sent to internment camps in places like national parks. One of those camps was here at Cave and Basin.

The area by the lower boardwalk is a birding and wildlife hotspot/Jennifer Bain

My pilgrimage to the birthplace of Canada's national park system ends outdoors on aging boardwalks with fading interpretive panels — something the management plan hopes to tackle — as I take in the thermal waters, wetlands, vent hole of the cave and remnants of that first hotel.

The warm water of the marsh attracts birds like the Killdeer and Robins that would normally fly south in winter. I spot white-tailed deer and what appears to be the aggressive mosquitofish that were introduced in 1924 from the United States for mosquito control. The Banff longnose dace, a rare minnow that only lives in these warm waters, is nowhere to be seen.

There are areas just off the boardwalk that are out of bounds to protect a wildlife corridor. But one species clearly didn't get the message to stay in the woods away from humans. Elk are regulars in the parking lot, to the delight of those who think they're just coming here to see water.

Amar Athwal shows a vintage photo of people swimming at what's now Cave and Basin National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain