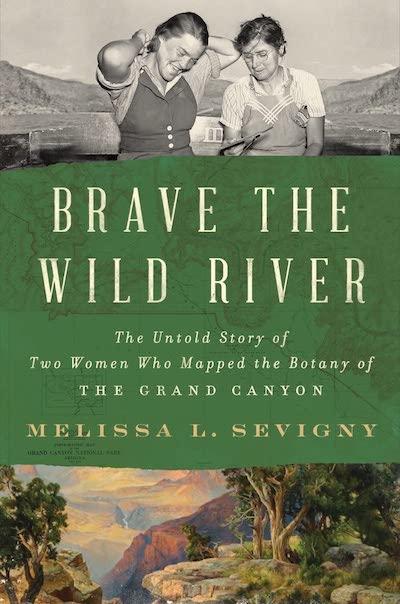

In 2023 if a woman wishes to run the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, she can, and many do. If she decides she wants to be a scientist, or a science journalist, she can do that too. Melissa Sevigny, a science journalist, rafted the Colorado through the Grand Canyon to visualize the journey two botanists, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter, made in 1938, the first women to successfully boat the canyon.

For many reasons, doing so was not easy back then, and Sevigny makes the reasons very clear in her account of their adventure. Doing the trip, considered risky for anyone, was a triumph for them in several ways — they cracked gender barriers a bit for adventure and in field science. The prevailing view in 1938 was that only foolish risk takers, and men, should undertake such a venture. Women doing such things, and in pursuit of science on such a trip was for many unimaginable and even scandalous, invasions of a man’s world. Elzada and Lois made this journey, and author Sevigny does a marvelous job of telling their story.

Eighty-five years after Clover and Jotter joined Norm Nevills, a famous name in the history of Colorado River running, on his first run through the canyon, Sevigny gives their journey the attention it deserves. She brings the expertise of a science writer to a story partly about science and the challenges of women’s place in it, about the botany of the Grand Canyon, and many other aspects of the time and place.

Sevigny has researched the stories of Clover's and Jotter’s lives leading up to their trip, mining the women’s journals and other sources. She describes how determined Clover was to botanize through the canyon since one of her professional goals was to catalogue all the Southwest’s cacti, and she saw the trip as helping reach this goal and establish her in her field.

Sevigny writes, “The Colorado River’s canyons had been mapped by surveyors and river runners, but never by a botanist. ... Whatever she found would have value: beyond the pure thrill of taxonomy, it was a chance to see how the flora of the surrounding deserts mixed and mingled in the unique setting of a series of deep canyons.”

Since “it was hardly appropriate in the prudish 1930s for Clover to disappear into a remote wilderness in the company of only men,” she invited 23-year-old Lois Jotter to join her. Jotter, who had some backcountry experience and a yen for adventure, was working on her botany PhD at the University of Michigan where Clover knew her as one of her students.

Sevigny is a fine writer and tells the story well. Her account is based on broad research and on her understanding of science and especially botany. She describes constraints and challenges women faced historically in science and society generally, and she knows the histories of the Colorado River and its explorers and river runners. The journey down the river is the core narrative, and Sevigny made that journey in 2021 as part of her research. She weaves in snippets about Southwest history, geology, Indigenous people, women in science, and characters in Grand Canyon river-running history, like Buzz Holstrom and Emery Kolb, placing these stories at sites she knows along the river.

Brave the Wild River is an adventure story, as the title suggests, and Sevigny describes the trip and its hazards, including the relative inexperience of most of the party, the river’s rapids, male egos, ups and downs of party morale, and poor decision-making by leader Nevills. As they prepared to launch on the Green River, the group of onlookers told the party they were in for it, sharing stories of the dire fates of earlier adventurers, most of which were exaggerations or simply false. Clover was undaunted and, according to Sevigny, her flippant response was, “Well … if we don’t come back just toss a rose over into the canyon for us.”

Off they went down the relatively peaceful Green River, which gave the crew a few days to get acquainted with each other and their three boats. Then they arrived at the confluence of the Green and the Colorado rivers and adventures began. “Downstream from Jotter’s campsite, the Colorado River swept on into deepening canyons, one after the other — through Cataract, Glen, and the Grand Canyon, 277 miles long and so deep it exposed the raw bedrock of the world.”

The rivers were running high and, in Cataract Canyon they, as Lois Jotter stranded alone by a mishap thought, had failed their first test. Earlier Nevills had pulled the boats to shore to scout the first rapid.

The river was high with snowmelt, chewing up whole trees and spitting them out like toothpicks. Then a boat pulled free from its mooring and spun into the current, Jotter heard a shout and dashed to the shore to see the boat sail by, captainless and undirected. Recklessly she followed her oarsman, Don Harris, into a second boat to give chase. Harris rowed while Jotter bailed water with an empty coffee can, hands cut and bleeding from its jagged rim. Battered and breathless, the two swept four miles downstream before finding the lost boat aground. Harris left Jotter there and walked upriver to rejoin the rest of the crew, promising to return. Night fell. Nobody came.

This misadventure turned out well, but could have ended the expedition before it really got started. As Sevigny tells the tale, the crew and their three plywood boats, designed and built by Nevills, managed to escape one scrape after another. The women proved to be among the toughest and most resourceful members of the group.

When, running behind schedule, they reached Lee’s Ferry, one of the two places they could leave the river (the other being Bright Angel Creek) and could be contacted by the press, they entered a media frenzy. They also encountered Buzz Holmstrom, who had achieved a first on the river a year earlier — a solo descent of the Green and Colorado, all the way from the headwaters in Wyoming to Lake Mead behind Boulder Dam.

In an earlier interview reported in a Saturday Evening Post story about his achievement, Holmstrom had remarked about the fate of Glen and Bessie Hyde, honeymooners who had tried to run the Colorado in 1928 and disappeared without a trace. “Women have their place in the world,” Holmstrom declared, “but they do not belong in the Canyon of the Colorado.”

Journalists besieged the party at Lees Ferry, but Holmstrom did not repeat this misogynistic view when accosted by them as they covered the party during their layover. Sevigny writes: “No matter. Plenty of other people were more open on this topic. ‘Experienced river men around Boulder City,’ the journalist wrote, ‘unwilling to be quoted directly, have stated that they consider the presence of the women in the party as one of the hazards, as they are ‘so much baggage’ and probably would need help in an emergency.’”

Holmstrom, after meeting the party and spending time with them, particularly with Lois Jotter, wrote his mother, “The women on that party are really doing better than the men.” Learning how right Holmstrom was in this assessment is one of the rewards of reading Sevigny’s account.

One episode at Rainbow Bridge also illustrates how misogyny and gender roles were part of the expedition. The party explored the national monument, which was so hard to reach that few tourists had ever been there.

Jotter soon tired of exploring and found a quiet corner with Atkinson [W. Eugene Atkinson, a zoologist from the University of Michigan who accompanied the women] to talk. Nevills assumed the two of them spent the time napping and disparaged Jotter’s laziness. “Anemic probably,” he wrote, “tho she looks big and husky.” Evidently he had forgotten that both women woke before dawn each day, cooked breakfast, stowed their bedrolls and sometimes even collected and pressed a few plants before any of the men opened their eyes.

In another incident, the party pulled off the river to visit Vasey’s Paradise, which the botanists knew from earlier accounts to be rich in plant life — John Wesley Powell had been so impressed by the plants there that he had named it for a botanist, George Vasey. This was an opportunity to consider the limits of C. Hart Merriam’s neat life zone theory, which revolved around the hypothesis that there was a relationship between plants and climate at elevations that was similar to that observed at latitudes from south to north latitudes. In other words, the higher up the mountain one went, the more like northern latitudes was the vegetation.

Merriam had visited the Grand Canyon in 1889 and realized that perhaps his theory was not as explanatory as he had thought. He found the Canyon “a world within itself” and ‘a great fund of knowledge is in store for the philosophic biologist whose privilege it is’ to study it.”

Sevigny writes:

Clover and Jotter had no time for philosophy. They had barely an hour to spend at Vasey’s Paradise. “We collected furiously,” Jotter wrote in her logbook, heedless of a light rain…. By noon the men were waiting hungrily for lunch. Clover suggested mildly they get out the canned food and cold biscuits (left over from breakfast) and feed themselves. But when the two women finished putting up their samples in newspaper, they found the rest of their crew “waiting big-eyed & expectant under a rock.”

In a rare moment of impatience, Clover wrote, “We have spoiled them completely.

The men had no interest in the scientific aspects of the expedition, Nevills especially, and they barely tolerated the women’s desire to botanize throughout the trip. Nevills as leader resented any stops for botanizing, and he and the other men clearly thought the women’s role on the trip should be as it was elsewhere, to serve their needs, regardless of the desires of Clover and Jotter.

Sevigny’s account touches on several interesting elements of the story of the Grand Canyon and of Grand Canyon National Park. For instance, when they stopped briefly at Lees Ferry, Clover and Nevills traveled to the South Rim and met Grand Canyon National Park Superintendent Miner R. Tillotson, who made clear he did not approve of their expedition, though he didn’t have the power to do anything about it. He would issue a permit to Clover to gather plants within the park. “However,” he added, “because of the dangers involved, especially to inexperienced boatmen and adventure seekers, we naturally do all in our power to discourage such trips.” He told Nevills the Park Service would do nothing to help if the party got into trouble on the river within the park.

Elsewhere, Sevigny briefly explains the Colorado River Compact, and how in the early 1920s the United States Geological Survey sent an engineer/ hydrologist named Eugene Clyde La Rue down the river on an expedition to search for sites to dam the river. La Rue "labelled the rapids with numbers, as if trying to eliminate their mystique in the most humdrum way possible. Numbers – that’s what was needed, not Powell’s romanticized and terror-inducing names.” La Rue envisioned “a ‘heel-to-toe staircase’ of dams and reservoirs that minimized evaporation, maximized hydropower, and controlled floods.” Sevigny summarizes La Rue’s fate and that of such ambitious development plans, though a dam was built that flooded Glen Canyon.

Sevigny explains how in 1994, 56 years after the Nevills' expedition, Lois Jotter-Cutter was invited on an Old Timers Expedition to raft the Canyon as part of a government effort to understand how Glen Canyon Dam had changed the river. Elzada Clover had died in 1980 at the age of 84. Jotter-Cutter was 80 years old and had not returned to the Colorado River. The canyon and river had changed in many ways and when asked what stood out to her on this trip she replied, “I recognize that there [are] many individual small differences. But the feeling that you get when you look up and see one high wall lit up, and the rest less so . . .”

Her account of the Old Timers Expedition gives Sevigny an opportunity to review the significance of Clover and Jotter’s adventure.

In the Epilogue, titled “A Woman’s Place,” Sevigny tells how she had Clover and Jotter in her mind during her own float through the Canyon. “Sometimes I felt their presence so strongly,” she writes, “that I turned round at the foot of a rapid, half-expecting to see a ghostly Cataract boat cresting a wave." She continues:

What would have happened, I wondered, if Clover and Jotter never ran the river — if they had listened to the critics and doomsayers, or to their own doubts? They brought knowledge, energy, and passion to their botanical work, but also a new perspective. Before them, men had gone down the Colorado to sketch dams, plot railroads, dig gold, and daydream little Swiss chalets stuck up on the cliffs. They saw the river for what it could be, harnessed for human use. Clover and Jotter saw it as it was, a living system made up of flower, leaf, and thorn, lovely in its fierceness, worthy of study for its own sake. They knew every saltbush twig and stickery cactus was, in its own way, as much a marvel as Boulder Dam – shaped to survive against all the odds.

In her closing paragraph Sevigny writes, “Like others before them, Elzada Clover and Lois Jotter valued their curiosity about the world more than their presumed place within it. They go ahead and, like stars reflected on the river, show the way.”

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places