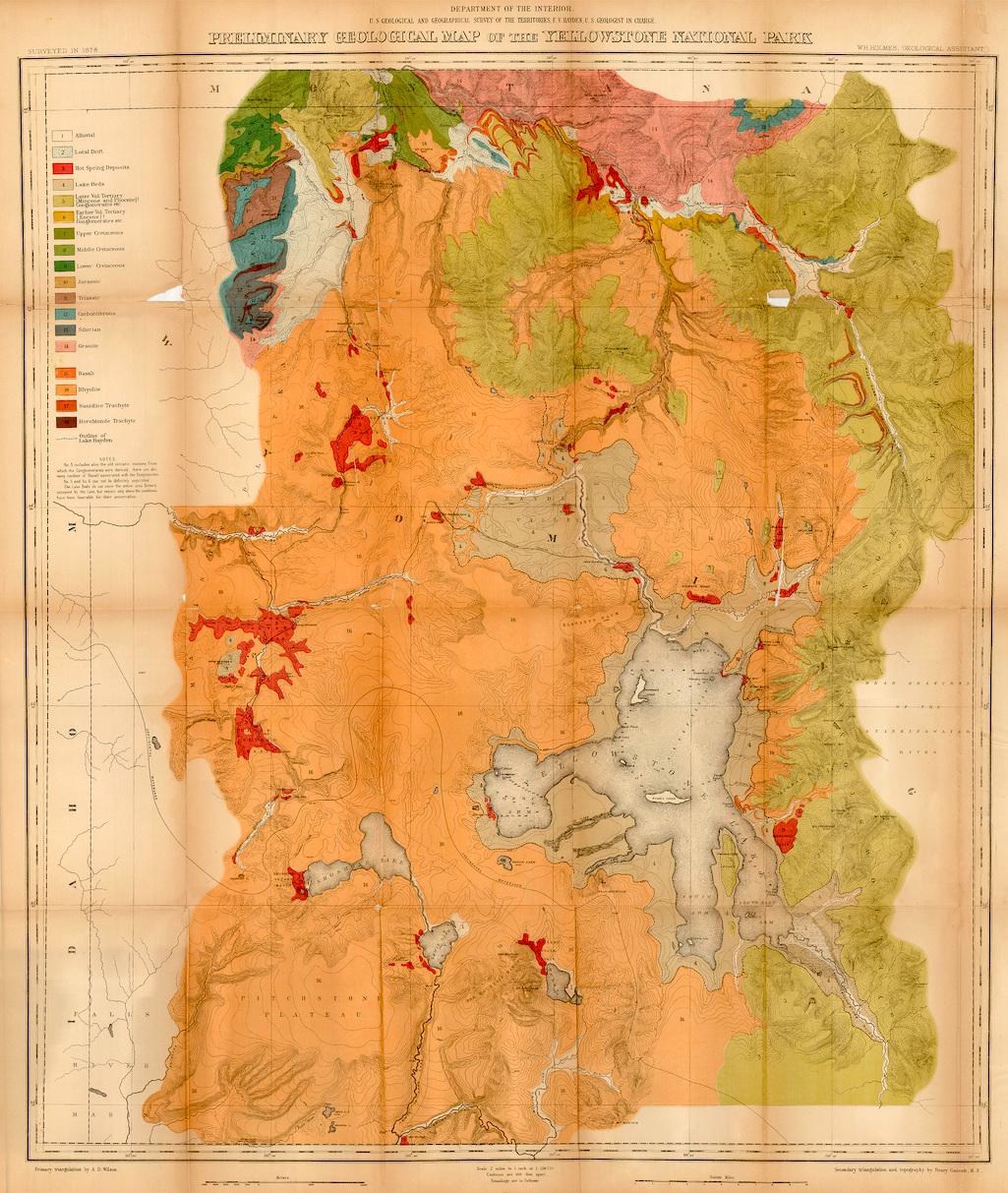

The first geologic map of Yellowstone National Park was created in 1878.

Editor's note: Yellowstone Caldera Chronicles is a weekly column written by scientists and collaborators of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory. This contribution is from Michael Poland, geophysicist with the U.S. Geological Survey and Scientist-in-Charge of the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory.

Geological mapping requires a high level of skill in Earth science, willingness to go into remote wilderness areas and endure rugged conditions, patience, perseverance, and curiosity. Today, mapping is aided by satellite and airborne data, and an ability to drive close to most areas of geological interest. But imagine being a geological mapper in the 1870s!

The volcanic character of Yellowstone has long been known. An Indigenous map drawn on a bison pelt and indicating a volcano on the Yellowstone River was described by the governor of Louisiana Territory in an 1805 letter to Thomas Jefferson. The first formal geological studies of the region, however, were not undertaken until the 1870s.

In 1871, the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, led by geologist Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden, took on the task of conducting a detailed exploration of the region that is now Yellowstone National Park. The exploration provided a preliminary assessment of the geology of the area, and the maps, reports, photographs, paintings, and descriptions were the primary motivation behind the creation of the National Park. The work even involved mapping the coastlines and depths of Yellowstone Lake—incredible work for the time done using an 11-foot-long boat.

Additional work occurred in the years that followed, prompted by the attention that the region had received after the 1871 survey. The United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories returned to Yellowstone in 1877 and 1878, when topographical surveys by cartographers Henry Gannett and Allen David Wilson established the most accurate map of elevations and landforms of the time. It was also in 1878 that William Henry Holmes conducted a detailed geologic investigation of the new national park. Although a few investigations of the park’s geology had been undertaken by that time, Holmes pointed out that “geologists have but glanced at the surface features of the country, and that the more profound and intricate problems remain almost untouched.”

Holmes spent about two months mapping the park’s geology during that summer, although, as he says, “during nearly one-half of this time storms of rain and snow prevailed to such an extent as to greatly interfere with the work.” Ah, summertime in Yellowstone…

Despite the conditions, Holmes was meticulous and thorough. He charted the course of his exploration and noted the locations where specific observations were made. His geological field work is stunning in its detail, with descriptions of rock units that include their thicknesses and physical characteristics—critical information for understanding the area’s geological history. Holmes also produced numerous sketches and descriptions of the relations between rock units—for example, of the Mount Everts unconformity between sedimentary rocks (that he correctly recognized as being over 65 million years old) and much younger rhyolite ash flow deposits.

Geology of the unconformity on Mount Everts in Yellowstone National Park. Sketch at the top was made by geologist William Henry Holmes in 1878 and correctly identifies Cretaceous sediments overlain by much younger rhyolite rocks, including fine ash deposits (“tufa”). The photo at the bottom shows the same outcrop as viewed from Mammoth Hot Springs/USGS, Mike Poland, October 10, 2021).

The map that Homes produced—a work of art in itself!—represents the first complete geological map of Yellowstone National Park, and it is surprisingly accurate. Although the current geological map, published by Robert Christiansen and collaborators in 2001 after decades of work, contains far more detail about rock units and structures, like faults and eruptive vent locations, the 1878 map correctly represents the major features of Yellowstone. These insights included the large extent of relatively recent rhyolite rocks, the presence of a much older series of volcanic rocks in the eastern part of the Park (these being derived from the Absaroka volcanoes that existed 43–53 million years ago), the geological epochs to which the various rock units belong, and that the area had been recently glaciated based on the presence of granite “bowlders” sitting on the surface in many locations (this surficial geology was later mapped in detail by USGS geologist Ken Pierce and collaborators). Holmes did not recognize that the region was home to several calderas—that came much later, in the 1950s and 1960s—but did understand the widespread importance of volcanic activity in the region.

Many of the rocks that Holmes collected were examined under a microscope, in thin section, by Clarence Dutton, a geologist who later led the branch of volcanic geology for the fledgling U.S. Geological Survey (founded in 1879) and who spent several months in 1882 observing active volcanism in Hawaiʻi. Also in 1878, geologist Albert Charles Peale (great-grandson of Charles Wilson Peale, the famous artist of the American Revolution era) observed the geyser basins of Yellowstone, keeping meticulous notes of the characteristics, eruptions, temperatures, and sizes of individual geysers and hot springs—information that is still used today to understand how those features have changed over time. Peale’s geyser basins are clearly depicted on the 1878 geological map of Yellowstone National Park.

It is difficult to imagine the challenge of mapping the geology of Yellowstone in 1878. Roads were limited, and transportation was by foot and by horse—much of the time in the field was spent simply trying to get from one location to another! In addition, the tools were the eyes of the geologist, compass, notebook, and pencil. Cameras were cumbersome, so many geologists had to double as artists, sketching the field relations they observed on scales ranging from small outcrops to expansive mountain vistas. Mapping today is aided by air photos and satellite images that are important for precisely locating contacts between geologic units; in 1878, there were no such tools to help guide field investigations.

At the end of this exceptional effort, Holmes recognized that he was merely investigating the tip of the iceberg in terms of the geology of the region. “…if I could have consumed years instead of months in the study of the 3,400 square miles comprising the Park, I might justify myself in putting my observations on paper…I have, consequently, gone just far enough to get glimpses of the splendid problems of the rocks, and to enable me in the future to appreciate and understand the classic chapter that this district will some day add to the great volume of written geology.”

Indeed, Yellowstone has become one of the best places in the world to study caldera systems. The 1878 geological map provided a foundation upon which all of that subsequent work has been built.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places