Parks Canada heritage presenter Nigel Wells shows writer Jennifer Bain how to fire a rifled musket at Signal Hill National Historic Site/Parks Canada, Lauren Gover

The year is 1862 and I’ve enlisted in the Royal Artillery to help protect Newfoundland. I nervously report to the Queen’s Battery Barracks in St. John’s, don a shell jacket and forage cap and prepare to handle a rifled musket for the first time.

“I’m going to load three rounds into this, you’re going to fire three rounds and later I’ll clean multiples of three rounds out of it,” says fellow Royal Artillery member Nigel Wells. “So in effect, I do all the dirty bits, you do all the fun bits, right?”

Wells half-cocks the long gun — a muzzle-loading, percussion cap, Enfield 1861 artillery carbine — and hands it over as we stand on an escarpment overlooking the harbor, which we locals call the Narrows. I clumsily move the hammer back to the full-cock position, slowly raise the gun to my shoulder, aim over the distant Fort Amherst lighthouse and cautiously squeeze the trigger.

Boom. I’m relieved there’s no recoil.

Parks Canada heritage presenter Nigel Wells in an 1857 Royal Artillery undress uniform/Jennifer Bain

“Right on,” says Wells, who in real life is a heritage presenter here at Signal Hill National Historic Site in what’s now the province of Newfoundland and Labrador. “I’ll take that from you and we’ll run you through two more rounds. Good stuff.”

Parks Canada interpreters offer free rifled musket demonstrations daily at Signal Hill in July and August from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. Upgrading to a hands-on experience costs $33.03 ($25 USD) — a price that also includes the entry fee and access to the visitor center that details how this site once protected St. John’s from military attack and is where Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi received the world’s first transatlantic wireless signal in 1901.

There’s a flintlock musket (“Brown Bess”) in the interpretive center that you can pick up to get a sense of the weight that British infantry soldiers once had to carry. But the carbine used for demonstrations is something different.

One of the guns aimed at the mouth of St. John's Harbour from the Queen's Battery Barracks/Jennifer Bain

“This particular gun was made in the 1970s by Parker-Hale on the original machining, so it’s kind of wrong to call it a reproduction when it was made by one of the original contractors on the original tooling,” explains Wells. “It is simply new production. That means we have modern gun steel for the barrel so they’re exceptionally safe which is part of the reason we offer this program. So, it’s not a case of having a 200-year-old carbine in use or anything like that.”

He and his co-workers make small white paper cartridges and fill them in the powder laboratory with “a suitable charge” — in this case 110 grains of 2F black powder.

“It counts as a blank charge is the way to think about this,” Wells assures me. “There is no projectile and as a result we’re just firing out over the Narrows because that’s where we get a really good echo from and it constitutes our safe range.”

He deftly preps the gun for a second shot — using percussion caps as an ignition source — as people on a guided tour gather at a safe distance, cameras at the ready.

The view of Signal Hill National Historic Site from the top of the Ladies' Lookout Trail/Jennifer Bain

Boom — the brief but intense sound is only slightly muffled by my expanding foam ear plugs.

“Wonderful,” says Wells.

“Not sure if the wedding party up on the cliff there was ready for the three-gun salute or not,” he adds, pointing up the hill from the barracks towards Cabot Tower.

I’m wearing my own glasses and Parks Canada has issued me a shell jacket as personal protective equipment. “It’s to get natural fibres over everything in the event that we have a spark event, which we will not have, and if we do then I would recommend buying a lotto ticket as this is statistically really quite unlikely,” Wells says.

You’d think I’d get better with each round, but I’m out of my element and so have to be reminded to fully cock the carbine for the third and final shot.

Boom. This time I take a moment to watch the smoke and flame dissipate and revel in the smattering of applause from the onlookers.

Heritage presenter James Dinn leads a tour through Signal Hill from the Queen's Battery Barracks up to Cabot Tower/Jennifer Bain

“Good stuff,” says Wells as we head to the barracks to sign the logbook. “The conceit of the program as originally written — although we’re not stressing that too heavily right now — is that you’re inducted as an honorary member of the Royal Newfoundland Company — now the Royal Artillery,” Wells says.

I guess I could be trained to prevent enemy vessels from entering the Narrows. Returning the jacket and cap and leaving the 1860s for 2022, I fret about what might happen when I have to go through airport security to fly home in less than 24 hours. “You’re not going to have any issues traveling with this after — I pop positive for black powder all the time,” says Wells. “Just show them the photos of what you were doing and they’ll understand.”

He's right — I sail through security and am secretly disappointed when I don’t get randomly selected to be swabbed for explosives.

Inside the Queen's Battery Barracks, cots and clothes are laid out to view/Jennifer Bain

My camera, though, is full of photos of a day immersed in Signal Hill’s defence and communications history — except for firing the Noon Day Gun because it’s awaiting repairs, and watching the Signal Hill Tattoo performance because it’s on hiatus.

On an hour-long public tour, heritage presenter James Dinn details the fight for fish (cod) that made this area so attractive. European fishermen arrived in Newfoundland in the early 1500s and by 1600, England and France dominated and were fighting for control of the lucrative fishing grounds and establishing fortifications. St. John's was strategically located through the Narrows with "one way in and one way out," and Signal Hill at the mouth of the harbor was originally called "the Lookout" by the British military.

Signal Hill is home to one of 29 battlefields administered by Parks Canada.

The summit of the Ladies' Lookout Trail was once a 1762 battlefield/Jennifer Bain

Student heritage presenter Lauren Gover explains how on Sept. 15, 1762, in the last phase of the battle for North America between Great Britain and France, British troops forced France to surrender the city. The small battlefield is at Signal Hill’s highest point on what’s now Ladies’ Lookout Trail, which legend has it was the place women gathered to watch for ships carrying their sons, husbands and lovers.

Signal Hill’s most iconic image is Cabot Tower, which opened June 20, 1900 as a “perpetual memorial” of 60 years of reign by Queen Victoria and to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the European discovery of Newfoundland by Italian navigator/explorer John Cabot (which had long been the traditional territory of the Beothuk and Mi’kmaq peoples and their ancestors).

Cabot Tower was opened in 1900 to commemorate a queen and an explorer/Jennifer Bain

Today, it houses a gift shop and the “Waves over Waves” exhibit about Marconi and wireless communications by the Society of Newfoundland Radio Amateurs. Up on the roof you can see a flagpole that symbolizes how flags were once raised on this hill to signal the impending arrival of ships.

Marconi famously received the first transatlantic radio signal here on Dec. 12, 1901 with a message from Poldhu in Cornwall, England with the letter S in Morse code. Although guests on my tour insist that Marconi’s first transatlantic transmission was to South Wellfleet, Massachusetts, that didn’t happen until Jan. 19, 1903 and lays claim to being the first radio transmission to cross the Atlantic from the United States.

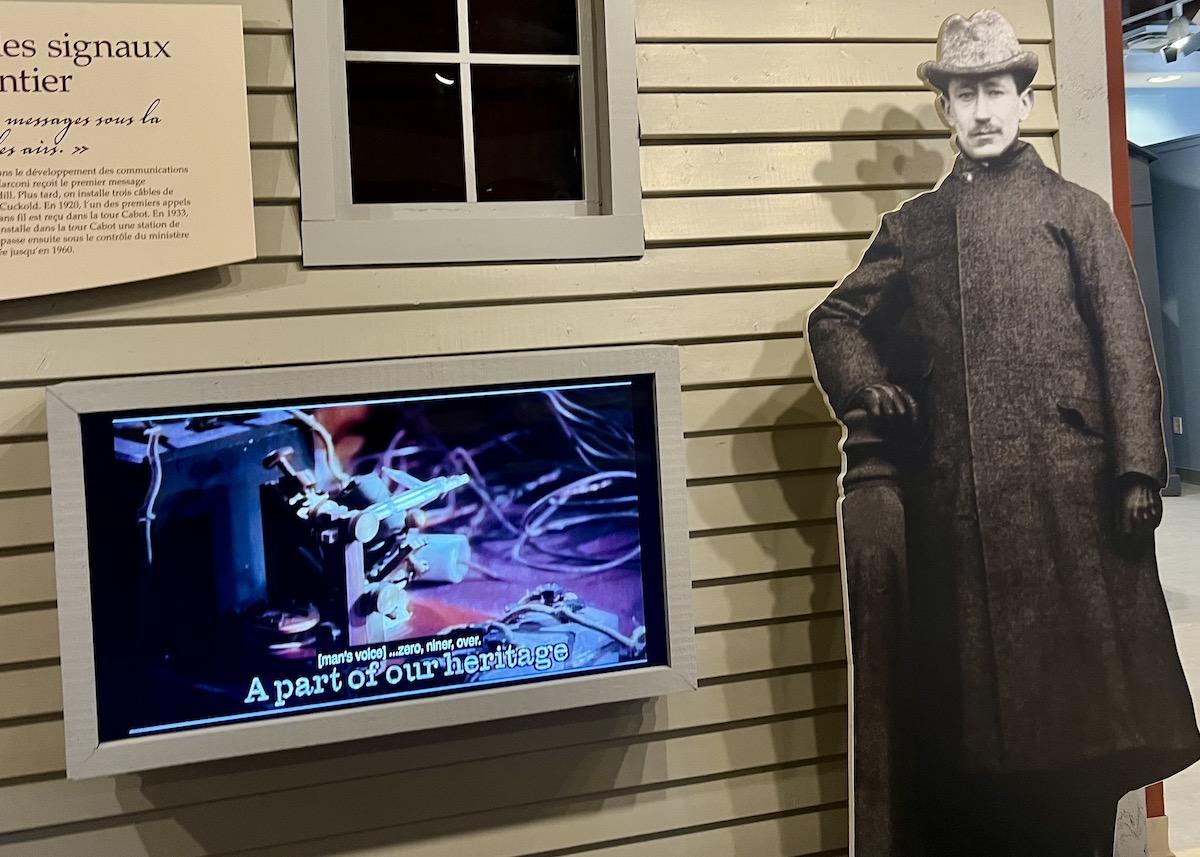

In the visitor center there is a cutout of Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi, who received the world's first transatlantic wireless signal here in 1901/Jennifer Bain

Marconi received the groundbreaking Newfoundland transmission in a vacant hospital room that once stood where Signal Hill’s upper parking lot is today. Between 1837 and 1840, two barracks were built across the length of the lot. They were later used as stores, a prison and a quarantine hospital for diptheria, smallpox and tuberculosis before being razed by a 1920 fire.

The parking lot is the jumping off point for two of Signal Hill’s five hikes — Ladies’ Lookout and North Head, which is steep and strenuous but draws about 35,000 people a year and ends when you cross the deck of a home into a colorful and defiantly ramshackle community called the Battery.

North Head Trail is steep and challenging with unparalleled ocean views/Jennifer Bain

It’s also where people pour off tour buses to peer at the ocean hoping for whales, icebergs and seabirds with their history lessons. Signal Hill draws devoted local hikers, joggers and dog walkers and is home to the annual event where people gather July 1 to view the country’s first sunrise of Canada Day. (Newfoundland only joined Canada in 1949 and mainly uses its own time zone, a half hour ahead of Atlantic Time, because the isolated island was a separate dominion when time zones were set.)

Down at the lower parking lot, past the electric vehicle charging stations and visitor center, is the Gibbet Hill Trail with astounding views of downtown and a macabre history.

On the Gibbet Hill Trail, a sign explains how gallows once stood here for a macabre practice known as gibbetting/Jennifer Bain

“Gibbeting,” explains a fading interpretive sign, involved dipping the bodies of executed criminals in hot tar, encasing them in an iron cage and chains, and hanging them on public display until they rotted to discourage would-be criminals and “comfort” friends and relatives of the victims. “A gibbet occupied this hill from the 1750s to about 1795, but it likely was not used often,” the sign says. “History tells of only one known case and another probable one — both in the early 1790s.”

I ponder Signal Hill’s nuanced history with a dark chocolate-covered oatcake from the Newfoundland Chocolate Company café inside the visitor center. The bistro tables are covered with the same local sayings as the company’s chocolate bars — things like “I dies at you” (you’re funny) and “hot enough to poison ya” (too hot).

It is hot enough to poison ya today at Signal Hill — Environment Canada has even issued a rare heat warning for the area and everybody is wilting.

At the Newfoundland Chocolate Company cafe in the visitor center, try a chocolate-dipped oatcake/Jennifer Bain

Speaking of warnings, I spot three signs with photos of a red fox reminding people that “human food kills wildlife” and that you can be fined at least $390 ($300 USD) fine for doing it. I’ve just read on Facebook that Parks Canada will close the top parking lot three days from now while it attempts to safely remove three foxes from Signal Hill. "People got into the habit of feeding them from their cars," laments Gover. "They seem pretty tame and pretty calm but they are wild animals and you never know when they can turn and hurt somebody. We've decided to relocate them to Terra Nova National Park."

Signal Hill does feel like an urban park, especially when you hike its trails. First opened as a national historic “park” in 1958, it typically draws 750,000 visitors a year but there are no gates to collect entry fees or properly count visitors. According to a 2018 management plan, only 12,000 visitors pay each year, generating minimal revenue to invest in visitor facilities, services and assets. That’s why Parks Canada offers revenue-generating experiences like firing rifled muskets and the Noon Day Gun.

On Signal Hill, people have fed the foxes and forced Parks Canada to relocate them/Jennifer Bain

When I flash my Park Canada Discovery Pass at the visitor center, keeping quiet about the fact I'm signed up for the rifled musket experience because the Noon Day Gun isn't possible, I'm surprised that nobody tries to upsell me.

"We don't promote a lot of our programs very heavily because our sandwich boards haven't survived and there could be wind," allows Wells. "We don't want to be advertsiting promises we can't deliver on." The musket program once drew a record 10 people, but generally it's more like two or three a day.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places