The Robert Gould Shaw Memorial is the starting point for the Black Heritage Trail in Boston/Barbara Jensen

Two Freedom Trails Of Boston: Urban National Parks

By Barbara 'Bo' Jensen

With inflation sending the costs of travel soaring, I was hesitant to set off on an expensive cross-country journey, much as I love the national parks. Yet, having endured a very cold New England winter confined to a Boston-area apartment, I was eager for a long hike in the warm sunshine. Rather than spend the hours and gas money to drive to Cape Cod National Seashore, I found a convenient local alternative: I decided to catch a train downtown to visit Boston National Historical Park and take a day hike along the Freedom Trail to connect with early American history.

Who knew national parks existed within major cities? Boston National Historical Park is a collection of urban national historic sites maintained by the National Park Service and local partners. It sounded touristy and fun; I could get a latte along the way. I had no idea that I was about to spend multiple days walking not one trail, but two, and traveling much deeper into history than I’d planned.

First, the Freedom Trail. According to the map I picked up at the visitor information center on the Boston Common, “The Freedom Trail is a 2.5-mile path on the city sidewalks that leads to 16 of the country’s most significant historical landmarks.”

A red brick path leads you down the Freedom Trail in Boston/Barbara Jensen

I am no historian, but it didn’t matter. A red double-brick line embedded in the sidewalks leads visitors from one landmark to the next, with an elaborate bronze medallion set into the brick trail at designated stops, an arrow pointing to the entrance of each site. It’s virtually impossible to lose your way. Multiple groups of school children on field trips easily followed the red brick trail with their teachers alongside guides in colonial costumes leading large groups of tourists, university students engaged in earnest discussion, and me with my coffee, all walking to Park Street Church and Granary Burying Ground, on past Old South Meeting House and Faneuil Hall and Old North Church, all the way out to Bunker Hill.

The truth of history lies beneath the surface, and a cemetery like Granary Burying Ground is a literal and blatant reminder, urging us to remember who is included in the history we tell…and who is not. It’s easy to find the gravestones of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere. But then, in a far corner, I read an interpretive sign about their young contemporary, the Black poet Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784). She was named for Boston businessman John Wheatley, who purchased the kidnapped eight-year-old African child as a slave for his wife – a child also named for the very slave ship that stole her away, the Phillis. John and his wife Susannah Wheatley are buried in the cemetery; they were considered progressive liberals of their day because they taught Phillis to read and write and allowed her to live in their house. But no one knows where Phillis Wheatley’s grave is. Or if she has one.

The image of that little girl alone on the auction block haunted me as I walked the rest of the Freedom Trail. Standing before the trail’s terminus at Bunker Hill Monument, a formal 221-foot granite obelisk, I imagined instead the earthen walls hastily constructed atop the hill, hundreds of men dying in the mud on both sides. Who were they? My warm afternoon sunlight was fading. The history I had retraced felt…incomplete, impersonal. Revolutions are huge, earth-shaking events, of course; but the voices of protest and the blood sacrificed, the lives lost, those belong to individual people. Many of whom looked nothing like the well-known Founding Fathers.

As I rode the train home, I found a small paragraph on the back of my map noting that “steps off the trail” I would find the Black Heritage Trail. “Keep your eyes open,” it advised.

And so, I return. Back at the Boston Common, I emerge from the Park Street train station and head for the information kiosk directly ahead. The red-lined Freedom Trail map takes up one full side of the kiosk, its highlights the adjacent side. Nowhere is the Black Heritage Trail shown or even noted.

All I know is that the Black Heritage Trail starts at the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial across from the Massachusetts State House. Here he sits, a white Civil War colonel astride his bronze horse, front and center in a relief sculpture of the all-Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment, his men anonymously surrounding him, the names of those who died in battle listed on the back of the 1897 monument.

As representation goes, I guess it was a start, one of the first monuments to Black Americans erected. But I need to follow this trail backward through time, to find out not just who died in service to the Union, but who lived and fought for the Revolution and our original ideal of freedom.

At first glance, the Boston African American National Historic Site is like the larger Boston National Historical Park, a similar collection of 1700-1800s meeting houses and churches and homes dedicated to the immediate causes of liberty and equality. But here, those causes feel closer, more intimate, more vulnerable – personal liberty, personal equality.

And more hidden. Finding the Black Heritage Trail on the north side of Beacon Hill is like reenacting travel on the Underground Railroad, following the unnamed blue-lined side route on my Freedom Trail map, searching quietly through the north side of Beacon Hill for each unmarked, unremarkable door, holding behind it a rich and inspiring story. Ironically, the Black Heritage Trail includes several secret safehouses, still hard to find, Underground Railroad stops standing right before our eyes.

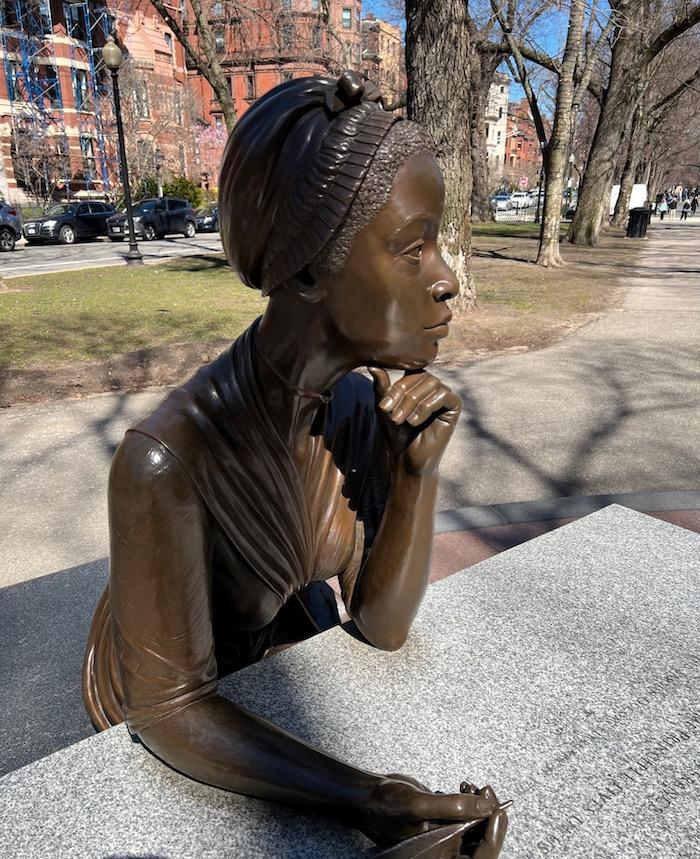

Phillis Wheatley was a young slave girl whose story is told within the Black Heritage Trail in Boston/Barbara Jensen

You have to know what you’re looking for. The black-and-white trail signs are few and far between, sometimes obscured by trees or trucks. I only found my way by downloading the National Park Service app, with directions and photos of the homes of people like abolitionist John J. Smith, escaped slave-turned-legislator Lewis Hayden (whose house was a fiercely protected stop on the Railroad), and John Coburn, founding captain of the 1850s Black military company the Massasoit Guards (who also defied the Fugitive Slave Law and rescued Shadrach Minkins from slave catchers). The app led me to the African Meeting House built by free Black men in 1806, and the Abiel Smith School, which now houses the Museum of African American History, with books, exhibits, and finally – a map.

The Black Heritage Trail extends between the Revolutionary and Civil wars and beyond, into the beginning of the 20th century. Along the way, I inadvertently found more sites, more names – the home of Rebecca Lee Crumpler, the first African American woman to earn a medical degree, in 1864, and the door to the house of John Sweat Rock (1825-1866), “A Free Black Man, Physician, Dentist, Lawyer, And Abolitionist Distinguished For His Professional And Civic Contributions To The Boston Community.” And the 1787 home of George Middleton, a Revolutionary War veteran and hero, who led the Bucks of America, a Black militia that fought in that muddy mess at the Battle of Bunker Hill. Look him up – he risked his life for Liberty, for all of us, and after the war continued to be an outspoken activist and community leader. Look them all up. It costs nothing. Their history is our history. It’ll open your eyes.

“In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle which we call Love of Freedom,” wrote Phillis Wheatley in 1774. “It is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.” A young Black family is walking in front of me, the kids skipping ahead toward Joy Street and the museum. “[T]he same Principle,” she continued, “lives in us.”

# # #

Read more:

Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral by Phillis Wheatley, “negro servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston, in New England,” originally published 1773, reprinted from the London Edition by Barber and Southwick for Thomas Spencer, book-seller, Market Street, 1793.

“How Phillis Wheatley Was Recovered Through History” by Elizabeth Winkler, The New Yorker, July 30, 2020.

Helpful links:

African American Trail Project: 12 more walking trails/tours throughout New England can be explored at https://africanamericantrailproject.tufts.edu/trails-and-walking-tours

National Parks of Boston: https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/national-parks-of-boston.htm

Charlestown Navy Yard: https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/cny.htm

National Park Service mobile app: https://www.nps.gov/bost/planyourvisit/app.htm

Barbara “Bo” Jensen is a writer and artist who likes to go off-grid, whether it's backpacking through national parks, trekking up the Continental Divide Trail, or following the Camino Norte across Spain. For over 20 years, social work has paid the bills, allowing them to meet and talk with people living homeless in the streets of America. You can find more of Bo's work on Out There podcast, Wanderlust, Journey, Months to Years, The Road She’s Traveled, Chiaroscuro, and www.wanderinglightning.com @wanderlightning [email protected]

Comments

Who knew?

The Park Service has had extensive operations in urban areas for some time. Many majore recreation areas were created in the 1970s

Ya!!!!! Exactly who does not know that there are national park in major cities?????? I read it as literal but I hope it was rhetorical.