Just off Florida’s southeastern Atlantic coast lies the only coral reef in the continental United States.

The reef stretches for nearly 350 miles from Port St. Lucie, on about the middle of the coast, down to the southern tip of the Keys. It’s long been a popular destination for snorkelers and divers, who are drawn there by its easy access, its warm waters, and its spectacular stands of elkhorn coral, magnificent barrel sponges, and majestic eagle rays. Meanwhile, anglers love to pursue the reef’s schools of sailfish, grouper, snapper, cobia, barracuda, mackerel, shark, African pompano, and wahoo.

The reef is long enough that it’s part of not one but three national parks: Biscayne, Everglades, and Dry Tortugas. Despite that protected status, though, the reef has been hit hard by a pair of major threats to its future existence: a rapidly spreading wasting disease and climate change-driven bleaching.

Now a new study says its fish population is being rapidly depleted, too.

The study, which examined 20 years of survey data on 15 species, found that the agencies in charge of overseeing its most important fisheries have allowed them to be overfished to the point that their continued reproduction has been affected.

“The southern Florida coral reef fishery requires urgent management intervention,” warns the study, published under the title, “Length-based risk analysis of management options for the southern Florida USA multispecies coral reef fish fishery,” in the May issue of “Fisheries Research.”

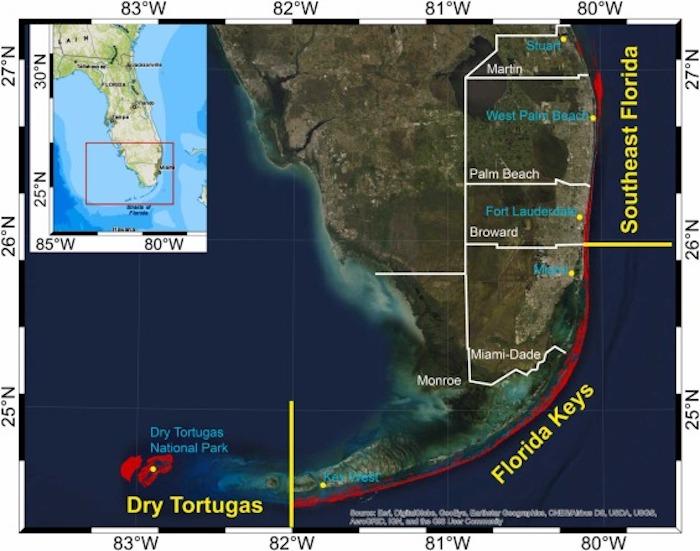

The Florida reef wraps around the lower half of the state/NOAA

The study found that 85 percent of the reef’s grouper and snapper species have been overfished to the point that their populations have now fallen below sustainable numbers. The species affected include some angler favorites, such as hogfish, yellowtail and mutton snapper, and red, black, and Nassau grouper.

Using computer modeling, the researchers found that spawning fish need to reach at least 40 percent of their historic levels for the population to be sustainable. Nearly every species of fish studied fell short of that level of reproduction. Some fell so far short they barely hit 5 percent.

Those findings should come as no surprise. The authors of the study are veteran scientists from the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. They have been warning about this problem for two decades.

“If they had listened to us 20 years ago, things wouldn’t be so bad now,” said lead author Jerald S. Ault, who chairs the University of Miami’s Department of Environmental Science and Policy. “But we’re now teetering on the brink of calamity.”

Ault expressed some sympathy for the regulators who failed to follow those recommendations in prior years. Efforts to curtail overfishing along the reef, he said, ran into “so much political pushback it’s off the charts.”

Ross Boucek of the non-profit Bonefish Tarpon Trust grew up fishing for tarpon and snook in the waters off Everglades National Park. Now a marine biologist who still enjoys fishing and sailing, he said the drop in fish abundance has been so noticeable that no one could miss it.

Trophy-sized mahi-mahi have all but disappeared from fishing tournaments in recent years, he said. And tasty mangrove snapper, which used to be so plentiful he could easily catch one in five or 10 minutes, “have become very challenging…That should not happen. That is a big sign of trouble.”

South Florida’s reef fish population has dwindled as South Florida’s human population has exploded, he pointed out.

“The recreational fishing fleet has gotten so large and efficient at catching fish that there’s now a need to recalibrate its management,” he said. “The recreational fishery has always been considered low impact compared to the commercial fishery, but the opposite is now true. “

Thirty or 40 years ago, Boucek said, his uncle and other charter boat captains followed the sensible practice of fishing a particular location on the reef no more than once every two weeks, allowing the fish population there to rebound.

“But then they stopped doing that,” he said. “They realized that if they were not there the next day, four other boats would be.”

Marisa Carrozzo of the National Parks Conservation Association said she was hopeful that the study’s depiction of such a significant fish population decline will spur everyone to act at last, despite prior political interference.

“Marine reserves in the Dry Tortugas have shown significant success,” she said. “After just five years of implementing a marine reserve at Dry Tortugas, studies have shown significant increases in the size and abundance of once overfished species.”

The NPCA sued the Department of the Interior and Biscayne National Park in December 2020 over the park’s failure to implement a no-fishing marine reserve zone and phase out commercial fishing. The suit remains active.

Marine reserves have been found to enable fish populations, such as those of Yellowtail snapper, to rebound. National Park Service studies in 2009 warned that overfishing was a "major threat" to the fisheries at Biscayne and Dry Tortugas national parks/NOAA

In 2015, the state and the Park Service had worked together to create a Marine Reserve Zone that would cover approximately 6 percent of Biscayne's waters, or 10,522 acres, and protect 2,663 acres of the park's coral reefs.

"A marine reserve is one of the most effective ways for us to encourage restoration of the park's coral reef ecosystem and it received strong support from the public during development of the plan," then-Superintendent Brian Carlstrom said at the time.

The reserve proposal drew support from such stars of marine science as Jean-Michel Cousteau of the Ocean's Future Society, National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence Sylvia Earle (who grew up on Florida’s Gulf coast), and Senior Scientist Emeritus Jeremy Jackson at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute.

But there were protests from the $6 billion-a-year South Florida fishing industry. That led a trio of Florida congressional representatives -- Reps. Carlos Curbelo, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen and Mario Diaz-Balart – to send a letter to the Department of Interior in which they objected strongly, citing the impact “on recreational anglers, charter-for-hire operations, commercial fishermen, fish houses, restaurants, marinas, and other small businesses.”

Meanwhile Florida’s two senators, Democrat Bill Nelson and Republican Marco Rubio, sponsored legislation to block the marine reserve from being established.

As a result, the Park Service shelved the plan. A state management plan issued subsequently omitted it.

“The Park Service must honor its word and advance these needed protections to preserve the iconic coral reefs and marine wildlife that people come from all over the world to see,” Carrozzo said. “The Park Service’s own experts agreed that these protectionary measures were needed back in 2014 and 2015.”

Instead of embracing the findings of the new study, though, Biscayne National Park spokeswoman Dani Cessna said that the park will continue to work closely with state officials “to improve the park’s fishery resources. Per our jointly developed Science Plan, the park is monitoring fishery resources to assess the effectiveness of recent fishing regulation changes within the park which aim to increase the abundances and sizes of targeted species in the park.”

As for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, which regulates what goes on in state waters, a spokeswoman said the agency disagrees with the new study’s methodology and therefore its findings.

The state agency “does not think this approach is appropriate for immediate application to fisheries management in southeast Florida and disagrees with the paper’s conclusions regarding the status of those 15 grouper and snapper stocks,” said Shannon Knowles, a spokeswoman for the conservation commission.

The state’s reasoning, she said, is that “when you assess the health of fish stocks at that geographic level (i.e., the southeast Florida reef tract), in many cases you are not accounting for the full extent of the stock.”

Other stock assessment studies conflict with the new study’s findings, she said. The new study “is based on a modeling simulation approach,” and as a result “we do not feel that their results are aligning with what could be considered ‘real world’ stock assessment methods that are routinely used for fisheries management in the southeast US.”

But Ault pointed out that state and federal management agencies base their stock assessments on what the anglers are hauling in, known as “landings.”

“They’re estimating from what’s on the dock about what’s in the reef,” he said.

The new scientific paper goes straight to the reef instead, Ault said. He compared it to estimating what’s in a grocery store by what people buy vs. going into the store and checking the shelves.

Ault also pointed out that most of those agencies’ computer modeling was developed for fish populations in the North Sea, where their reproductive period lasts only a few days per year. In a tropical setting like Florida, spawning goes on for months on end, he said.

Florida has declared itself to be “the Fishing Capital of the World,” Ault said. “But if we don’t get our act together in the next 10 to 15 years, it’s going to be bad news.”

Boucek said the management agencies need to take drastic action and do it quickly, because recreational anglers won’t voluntarily change their destructive habits.

“People will fish down to the last fish on the reef,” he said, “and then they’ll have a tournament to catch that last one.”

Marine reserves, such as the Dry Tortugas Research Natural Area, can help bolster the health of fisheries/NPS

Add comment