Steamboat Rock (center), at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers, from Harpers Corner in Dinosaur National Monument/NPS

My wife and I are staring at a lizard that must be four feet long, holding our breath in astonishment. Light tan in color, this creature is vividly outlined against an overhanging wall of sandstone. Painstakingly chipped out of the rock by some nameless Native American artisan, it has been on display here for at least 700 years, or longer than the Giotto frescos in Florence’s Santa Croce church.

Nearby are smaller lizard petroglyphs, along with strange anthropomorphs, representations of bighorn sheep, and a stylized, ornamented face, each emblematic of what anthropologists term the Vernal style of Fremont rock art. The Fremont people inhabited much of the Great Basin in Utah and Nevada for nearly a millennium, leaving behind masterfully realized rock art as well as dwellings, granaries, and crafts that hint at how they adapted to life in these challenging surroundings.

We are sampling the sights along a gravel road in Utah’s section of Dinosaur National Monument, a landscape of towering rock walls, upthrust anticlines, and sensual-looking, utterly bare hillslopes of multicolored mudstone. Located in the northernmost part of the Colorado Plateau Province, Dinosaur is famous for a particular outcrop of the Morrison Formation, in which the fossil collector Earl Douglass discovered the articulated tail bones of Apatosaurus in the summer of 1909. His find opened one of the greatest troves of Jurassic sauropod specimens in North America.

Earl Douglass discovered one of North America's greatest dinosaur graveyards/NPS

Douglass’s quarrying work for Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum led President Woodrow Wilson in 1915 to set aside 80 acres around the site as a national monument, using his authority under the Antiquities Act of 1906. Douglass ultimately supplied some 350 tons of fossil bones to the museum under federal permit.

In 1938, President Franklin Roosevelt expanded the monument by a whopping 203,885 acres, taking in the canyons of the Green and Yampa rivers and much of the surrounding plateau land. This, too, was accomplished under the Antiquities Act, which allows the president to set aside “historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest.” It was Franklin’s cousin, Teddy Roosevelt, who decided in 1908 that the Grand Canyon represented an “object” of scientific and historical interest, and so blazed a path that led to protection of many other magnificent Western landscapes, including Olympic in Washington, Grand Teton in Wyoming, and most recently, Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears in Utah.

My wife and I are due to take to the water the next morning along with six other folks, strangers to us, for an outfitted river trip down the 45-mile-long stretch of the Green River within Dinosaur. John Wesley Powell pioneered this river-level path in 1869 with a crew of nine men, beginning in the canyon he called Lodore.* He named it after a forgettable Romantic-era poem that depicts a 90-foot waterfall in England’s Cumbria district. The Green has no actual waterfalls, but its powerful rapids ran the No Name, one of Powell’s four heavy wooden boats, onto a rock, sinking it and destroying much of the expedition’s provisions. His men were able to retrieve some barometers, essential for determining their elevation, and a keg of secretly stashed whiskey, which Powell realized was salutary for the men’s dashed spirits. He named the rapid Disaster Falls.

Heading into Lodore Canyon in Dinosaur National Monument/Bessann Swanson

Disaster Falls along the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument/NPS

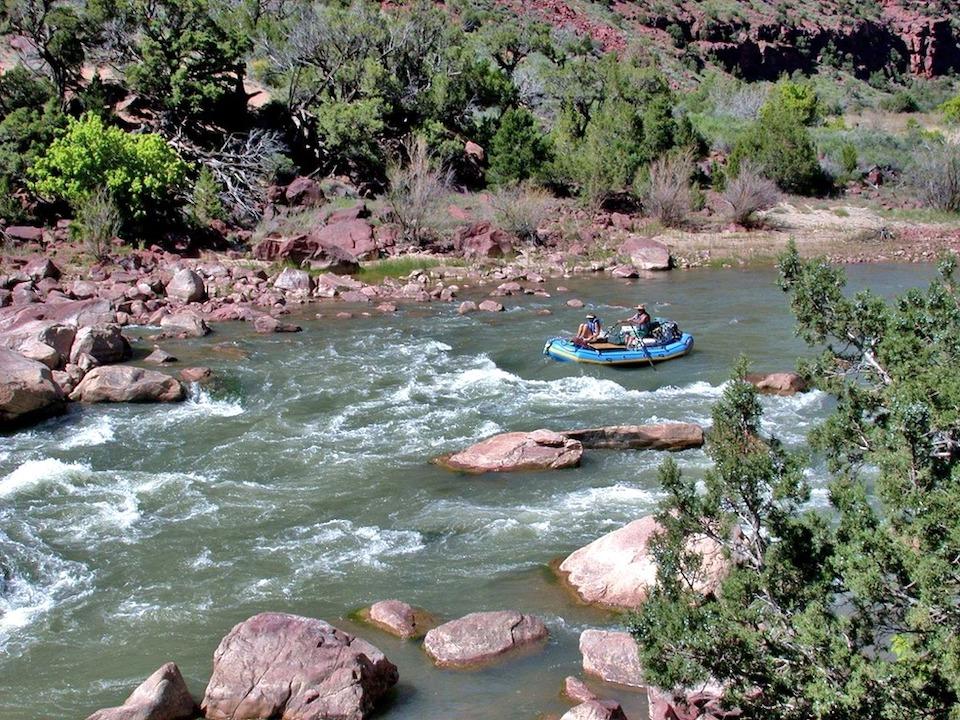

We contemplated Powell’s difficulties as we sipped beers in our lawn chairs the first evening of our float trip, the six of us spread out on a pleasant sandbar some miles below the rapids which swallowed the No Name. Our outfitter’s 18-foot neoprene rafts, as well as the knowledge and skill of our two guides, made the journey only mildly challenging. For three very full days—a short trip for this stretch of river—our little group floated through almost the entire north-south extent of Dinosaur. The long history of exploring this canyon stood in contrast to the ease and comfort we modern-day adventurers take for granted.

Every such trip, whether with an outfitter or privately run, is tightly regulated by the National Park Service to preserve the beauty and ecological health of the river corridor. Our hardworking guides showed us the use of porta-potties and cautioned us to not leave the tiniest bit of trash or food on the river’s shore. The regulations are enforced by NPS river rangers, who must enjoy one of the choicest jobs the agency offers. As a result we experienced near-pristine beaches, a good measure of solitude, and a thrilling though safe ride though Dinosaur’s major rapids.

We also experienced something that national monument status has protected here for more than 80 years: mile after mile of inspiring geology, much of which rivals anything on display within the Colorado Plateau Province. The monument’s landscapes grade from buff-colored desert around the fossil quarry to banded cliffs of limestone, sandstone, and quartzite in the main canyon. Lodore Canyon supports a forest of Douglas and white fir that suggest the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. The varied life zones within the river corridor host a considerable population of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep, bears, beaver, a variety of birds including bald and golden eagles, and 16 species of bats, which find ample lodging in cliffs and niches along the river.

We were treated to glimpses of all these creatures, except for bears. At our last camp, a beaver ferried cottonwood branches downstream to a presumed den, returning unseen through swift current to gather more. In that same camp, one of our guides played tug-of-war with a skunk that was trying to make off with the kitchen garbage. She won, thankfully, but the incident underscored the importance of not leaving food scraps behind that would habituate animals to human fare.

Dinosaur’s rapids make this float exciting in places, but whitewater thrills were not the main draw for my wife and I. Something else graces the canyons of the Green, a quality which we have been seeking along various stretches of this river for more than 35 years. Call it a sense of wonder, the feeling one gets when confronted with geology that mocks our inconsequential ambitions. It is the awareness we come to as we pass a bighorn ram standing guard next to a group of ewes, or when a golden eagle passes along a sheer cliff, its elongated shadow draped across the sunlit sandstone face. It can be as delicate as the sinusoidal track of a snake in the sand. Perhaps it is this same sense that inspired a meticulous Fremont craftsperson to outline a lizard in pure stone.

The cliffs which rise from the river and in places constrict its channel into rapids seem to raise up our souls, even as they diminish our egos. Perhaps they did the same for Powell’s men as they surveyed the wreckage of their boat. Like us, they must have appreciated the gentler ambiance of the riverside cottonwood groves. Because the river canyon can be reached by road at only a couple places, we could get a glimpse of the land as earlier eyes must have seen it, whether they belonged to river explorers, fur trappers, or even the long-ago Fremont.

Floating by Steamboat Rock on the Green River in Dinosaur National Monument/Kurt Repanshek file

That thread out of the past is a tenuous one, and in Dinosaur it came close to breaking. At one point on the second day’s float, we approached an outcrop of dark Precambrian rock, good solid stuff into which one could anchor a tall dam of concrete and steel. This was exactly what Bureau of Reclamation engineers had in mind for Dinosaur when they arrived at the monument in 1939, shortly after its creation, to survey dam sites in Split Mountain and Whirlpool canyons. The proposed hydroelectric dams would have flooded nearly the entire stretch of the Green within the monument to a depth of up to 500 feet, leaving the prominent landmark of Steamboat Rock in Echo Park as an island in the reservoir.

The story of how the Echo Park and Split Mountain dams were halted has been well told in books by Mark W. T. Harvey, Jon M. Cosco, and others. The battle lasted throughout much of the 1950s and helped give birth to the modern era of environmental activism. Utah’s fledgling river-running community, led by Vernal outfitter Bus Hatch, raised the alarm over these projects and drew support from the nation’s major conservation groups. As we floated through the shadows cast by what would have been the abutments to the Echo Park dam, I gave thanks for how this wondrous canyon was still there for us to enjoy.

There are many contradictions embodied in our national park system, one of them being that most patrons of places like Dinosaur are white, highly educated, and well off. Another is that most of our Western national parks and monuments lie on land that was the ancestral home of dozens of Native American tribes. I wish this were not so, and in time perhaps this will change.**

Four members of our party were immigrants to America, and they found the sights displayed along the Green to be amazing indeed. One of them told me, as we paddled along in inflatable kayaks, that the experience was life-changing.

I know what he meant. Something in me changed for the better when I first floated down a wilderness river. I knew then that our country represents more than ambition, cleverness, and the displacement of the poor and politically powerless. I learned that wise women and men have taken steps to keep the sources of wonder alive for all of us to experience. I plan to come back to places like Dinosaur for as long as I can, and I hope many others of all backgrounds will too.

# # #

*One of Powell’s crew members, an English adventurer named Frank Goodman, left following their perilous descent of Lodore, Whirlpool, and Split Mountain canyons. Three more would leave the expedition deep in the Grand Canyon, only to lose their lives under mysterious circumstances.

**One place where this did change, at least for a short while, was Bears Ears National Monument, which was conceived by a coalition of five Native American tribes in Utah and northern Arizona. I hope to see it restored some day to its original size and purpose.

Frederick Swanson writes about the West from his home in Salt Lake City. His new book Wonders of Sand and Stone: A History of Utah’s National Parks and Monuments (University of Utah Press) will be out this fall. His website is www.fredswansonbooks.com.

Add comment