Michael Allen beat the odds and worked for the National Park Service for nearly four decades/Courtesy

Michael Allen joined the National Park Service as a college student recruited in 1980 from South Carolina State University, a public historically Black land-grant institution, to interview people about the history and culture at Fort Moultrie National Historical Park. He climbed the ranks, but not everyone could fathom a Black man as park ranger.

“When people saw me in uniform, they thought I was a game warden, police officer, highway patrolman, security guard – anything but a park ranger. Once they even thought I was the valet to park the car,” he said.

Allen worked for NPS for 37 years, but he is unusual. Despite decades of efforts in Democrat and Republican administrations, there has been little progress in recruiting and retaining a workforce that reflects the increasingly diverse and multi-cultural American public.

Whites account for 79 percent of full-time permanent employees, and 62 percent of all employees are male.

Black employees comprise almost 7 percent of the NPS’s permanent full-time workforce, significantly less than the 13.4 percent of African Americans in the national population. Hispanic employees also are underrepresented, making up 5.6 percent of the Park Service general workforce despite accounting for 18.5 percent of the population. Asian Americans encompass about 2.3 percent of employees compared to 5.9 percent of the national population.

Only Native Americans at 2.5 percent of the workforce exceed their percentage of nationalwide population, which is 1.3 percent.

Beginning with the Kennedy administration just before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, diversifying the workforce has been an NPS objective.

Two years ago the Trump administration distributed an all-employee letter from Daniel P. Smith, at the time the Park Service's acting director. “We will attract, recruit, and retain a diverse workforce that assures our national parks and NPS programs reflect the diversity of America,” he said.

Smith’s statement reiterated support for Director’s Order #16 B: Diversity in the National Park Service that was issued by Jon Jarvis, President Obama's Park Service director, in 2012.

Yet, white males continue to dominate the NPS workforce.

“There has to be persistency and consistency in carrying through the commitment to diversity. It’s not a passive objective,” said Robert Stanton, the 15th Park Service director and the only African American to hold that position. He headed the NPS in the Clinton administration from 1997-2001, capping a 35-year-long career that began as a seasonal employee at Grand Teton National Park when Stewart Udall was Secretary of the Interior.

Stanton was also the agency's first African American superintendent, appointed by George Hartzog, Jr. who was director from 1964-1972. Committed to diversifying the NPS workforce, Hartzog named Stanton superintendent at the National Capital Parks-East region.

It’s difficult to create a diverse workforce for several reasons, including competition, the ability of seasonal employees to slide into permanent positions, and rules set by the Office of Personnel Management, said Phil Francis, chair of the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks.

Federal laws do not allow the applicant’s race or ethnic origin information to be shared with hiring officials. Even though an applicant is allowed to declare such information, the hiring official is not privy to receive it due to the race-blind approach of the process, said Kathy Kupper, a Park Service public affairs specialist.

Critics cite systemic racism as another reason for the lack of diversity.

James “JT” Reynolds, retired African American superintendent at Death Valley National Park, contends diversity efforts have failed because there are no consequences for managers who “blow off” diversity policies from headquarters.

“Whoever shared the thought that you cannot determine a candidate’s ethnicity, tells me something about the game used to overlook some candidates,” he said.

Over the course of his 38-year-career, Reynolds had opportunities as the selecting official responsible for developing the knowledge, skills, and abilities listed when advertising a vacant position and for reviewing the certification “cert” list -- candidates deemed qualified for the position by the human resources manager.

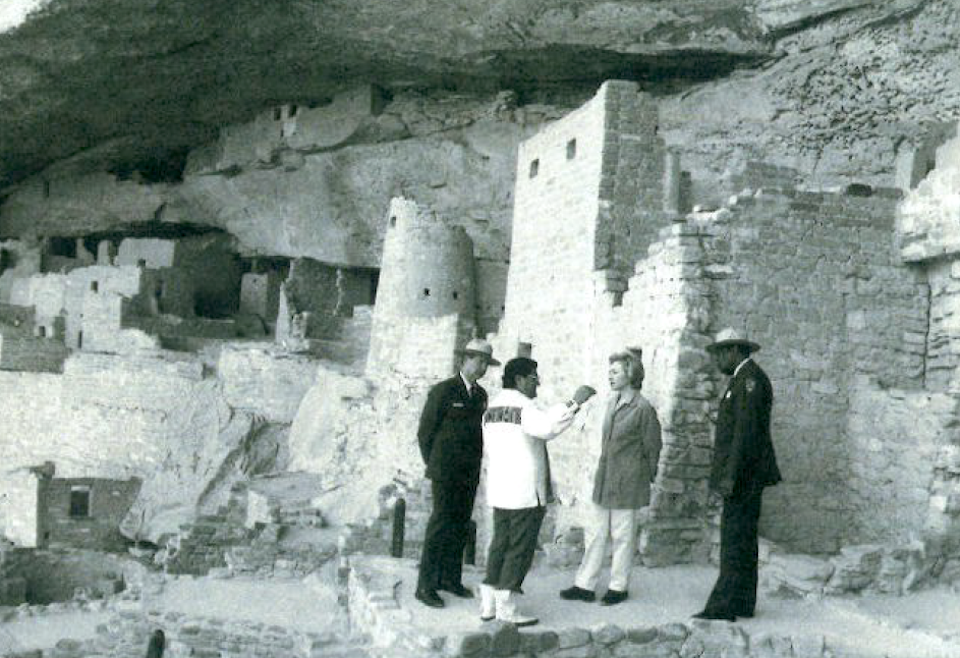

Bob Stanton, here with then-First Lady Hillary Clinton at Mesa Verde National Park, was both the first Black superintendent in the National Park Service and its first Black director/Courtesy

In his role as superintendent and a selecting official, Reynolds said he could “make a pretty good guess” to determine a candidate’s sex and ethnicity by reading the resume, name of college, spelling of the candidate’s name, and home location, and by calling supervisors and coworkers to learn more about them.

“I am sure the superintendent (if interested in diversity) sees all the names, and knows which candidates are diverse. I know I did,” he said in an email.

Stanton agrees that managers should have an understanding of what is expected of them regarding diversity and inclusion.

“Accountability starts with the director and becomes a shared responsibility up and down the line,” he said.

The National Park Service has recruitment programs that make it easier to get a job; there are “special hiring authorities that sometime permit vacancies to be filled by eligible candidates who qualify based on various elements such as public land corps internships or military service,” said Kupper.

For example, Allen was recruited through a cooperative education program allowing students to combine academic study with practical work experience that can lead to permanent employment. Soon after he was hired, he noticed that African Americans were mostly missing from the history the Park Service told in its exhibits and interpretive programs on Sullivan’s Island in South Carolina. White co-workers questioned his presence, but Allen refused to be intimidated.

“That experience, that journey, and those questions were my foundation to the work, activities, programming and whatever else I did for the next 37 years,” he said.

JT Reynolds rose to superintendent of Death Valley National Park/Courtesy

Over the course of his career, Allen recruited others “but often their experiences were not welcoming or positive,” he said. Allen, who retired in December 2017, suggests the agency talk with former employees and find out why they left the agency, if there’s a sincere interest in retaining people of color.

Another former NPS employee, Nina Roberts, faced years of rejection despite having experience working with parks and conservation organizations and a graduate degree.

“I’m one of many perfectly qualified women of color who applied for NPS jobs for a decade only to be turned down/rejected and in many cases, like mine, not even granted an interview,” she said.

Eventually the biracial woman was hired through a graduate internship program, now called Pathways, and later for a full-time education specialist position. By this time, Roberts was in her 40s.

She encountered some white men who “did not treat me kindly. I think they were threatened,” she said.

Roberts helped create a semester-long paid internship program at Golden Gate National Recreation Area for her students at San Francisco State University, where she is a professor in the Department of Recreation, Parks and Tourism.

“Now working in the halls of higher education, I still push the envelope from the outside. I find a place for students who want to work for the NPS,” she said.

NPS has had more success in establishing park units that speak to the country’s diversity – a goal sought by Hartzog when he was director.

In close to 40 states, the NPS has identified sites that reflect the American Latino heritage. There are more than 70 American Indian and 100 Asian American/Pacific Islander sites listed on NPS’s website.

When Stanton first joined the NPS there were only three units honoring African Americans. Today there are almost 40, along with the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

“President Obama brought in more sites to reflect more fully the face of America,” said Stanton.

The recent additions include Cesar Chavez National Monument in California, Stonewall National Monument in New York, Pullman National Monument in Illinois and Harriet Tubman Underground National Historical Park in Maryland.

Comments

Once again, I will state that the DOI, not just the NPS, has most of their postings on USAJobs as agency only (merit). Very rarely do I see them even advertise to the public. How are you supposed to become more diverse if you are selecting candidates from the pool you already have? They are not even trying! Why is their HR letting them advertise that way if they want a more diverse workforce even, from other agencies? They obviously do not want to solve this issue.