The loss of cruise ships this summer from Glacier Bay National Park is dealing the park a financial blow/Kurt Repanshek file

While national parks across the country are working on their reopening plans, staff at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve in Alaska is working on a plan to survive the loss of roughly 70 percent of its annual budget, a loss tied to cruise ships not leaving port for the park's waters this summer.

The financial hit is unique in the National Park System, where parks typically receive the bulk of their annual operating funds through Congressional appropriations. Glacier Bay, though, receives just 30 percent of its roughly $4 million annual budget from Congress. The rest comes from cruise ship fees.

"This year we’re not expecting any revenues, though there is a possibility that there may be some cruise ships in southeast Alaska. There are so many things that have to happen for that to occur," Glacier Bay Superintendent Philip Hooge said last week during a call from his office. “I personally don’t have much belief that we will see a single cruise ship. I know communities here remain hopeful. Right now, there’s nothing."

The global spread of the coronavirus has been a crippling blow to all facets of the tourism industry. Many cruise ship lines have curtailed large segments of their normal sailings. The Princess line announced three weeks ago that it was canceling all Princess Alaska Gulf cruise and cruisetours for this summer.

“This global outbreak continues to challenge our world in unimaginable ways. We recognize how disappointing this is to our long-term business partners and thousands of employees, many of whom have been with us in Alaska for decades,” said Jan Swartz, president of Princess Cruises. “We hope everyone impacted by these cancellations – especially our guests, travel advisor partners, teammates, and the communities we visit – understand our decision to do our part to protect the safety, health and well-being of our guests and team. We look forward to the brighter days and smooth seas ahead for all of us.”

While Alaska had been expected to see about 1.4 million cruise ship passengers this year, nearly 70 percent of the cruises into the state have been canceled, according to the state's Cruise Ship Lines Industry Association.

Hooge said his park largely has been recession-proof, but the coronavirus pandemic was a wild card because of its impact on the cruise industry.

“Glacier Bay usually is one of the less affected areas when there is a tourism decline, because we have a restricted number of vessels. It’s usually the last place that people cut vessel entries," he said. "So, Denali could see a 20 percent decline, for instance, with people coming there, and we wouldn’t see any (drop)."

The John Hopkins Glacier is a main attraction cruise ships treat their passengers to/Kurt Repanshek file

Glacier Bay's unique funding mechanism was created in the 1990s by former U.S. Sen. Frank Murkowski, R-Alaska, the superintendent said. While there are no entrance fees visitors pay at Glacier Bay, the senator was able to work out a deal where cruise ship fees to the park were based in part on passenger loads.

"It’s been a good thing for the park. It’s enabled us to be one of the better-funded national parks," Hooge said.

That fee structure, which generates roughly 95 percent of the park's fee revenues, has resulted in the park taking in about $13.5 million a year. That pot of money is broken down into a 60-40 split. The first 60 percent goes to the park as, in effect, its base operating funding, the money it normally would have received through a Congressional appropriation. The 40 percent is treated like traditional fees parks receive; parks hold onto 80 percent of those revenues, with the remaining 20 percent sent to Washington, D.C., for redistribution to less fortunate parks.

While Hooge has tried in years past to create a 'rainy day' fund with the excess fees, "nobody could have ever contemplated a 100 percent" drop.

"We’re good through the middle of next winter, March or so, and then it becomes tough," said Hooge. "If we get a normal (2021), or a year that’s anywhere close to normal, even 70 percent, then we’ll be OK in the long run. But we do have this gap between when we earn revenue and when we can spend it. It’s possible that we might be able to borrow against future revenues through some kind of exchange."

But the funding problem does create a scenario of the park not being able to pay a significant portion of its permanent workforce, something the Park Service has never encountered, according to the superintendent.

The fiscal bind has forced Hooge to postpone several projects he had hoped to move forward with this summer. One was the purchase of a sea-going vessel, one 70- to 90-feet long that could handle the open Pacific waters off the western shores of the park beyond the Fairweather Range.

The loss of the Alaskan Gyre to the USGS some years ago left Glacier Bay National Park without a large sea-going ship for patrolling its coastal waters/USGS

"Glacier Bay is the largest marine park in the National Park System and it doesn’t have a large vessel," explained Hooge. "It hasn’t had one for ten years. So we were hoping on replacing that large vessel. We have responsibilities for the outer coast in the park all year-round. We do not have a vessel that is capable of traveling to those waters. So we had saved our pennies to go do that. ... We have a huge marine responsibility since we have jurisdiction over Glacier Bay’s waters out to three miles. The park needs a large vessel."

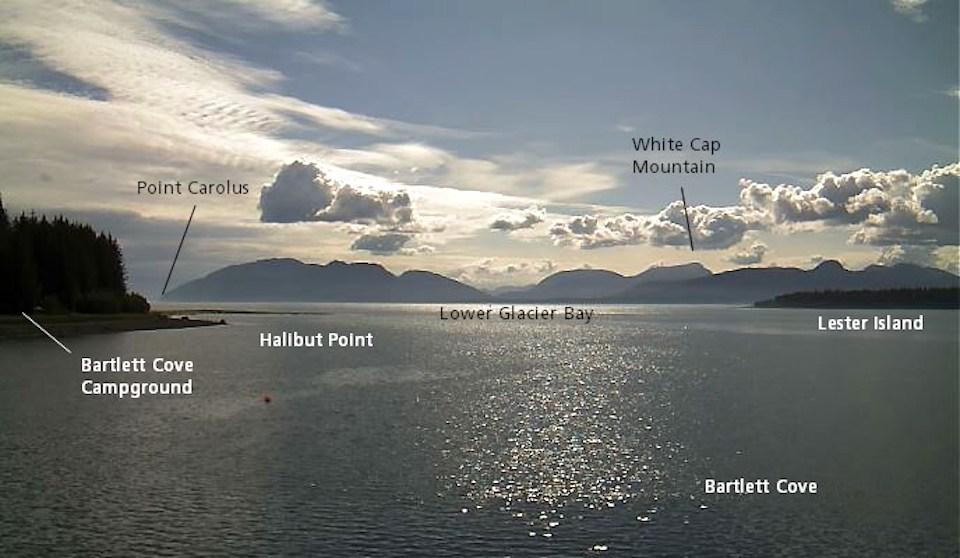

Also shoved aside was a plan to implement a front country plan around Bartlett Cove near the park's visitor center and lodge with hopes of enticing visitors to stay a bit longer. According to park staff, 35 percent of visitor groups spend only a day or two at the park, and 33 percent spend less than a day.

There currently is relatively little for guests at the Glacier Bay Lodge to do. While the park and preserve count more than 3 million acres, the developed footprint at Bartlett Cove is quite small, providing space for the lodge, visitors center, a dock, and a few short trails.

The Forest Loop Trail is a short, easy walk near the lodge at Bartlett Cove. It covers a mile of scenic rain forest and a bit of the shoreline. The route is a regular choice for a ranger-guided walk during the summer season, or you can easily make the trip on your own. The Bartlett River Trail covers four miles, roundtrip, as it meanders along an intertidal lagoon and through the spruce/hemlock forest before emerging and ending at the Bartlett River estuary.

Put off by the financial squeeze were plans to improve the front country of the park near Bartlett Cove/Kurt Repanshek file

The Bartlett Lake Trail runs eight miles roundtrip, and starts out on the Bartlett River Trail. About a quarter-mile down the trail the lake trail branches off and begins to climb the moraine.

"Bartlett Cove would function more like a traditional national park front country where visitors can 'Find their Park' and be inspired by the features, processes, stories, and attributes associated with the national significance of Glacier Bay—whether or not they are able to explore farther into the backcountry," the park's planning documents say. "The National Park Service would continue to provide the foundational services to access the backcountry, but would further expand its facilities, operations, and programming to engage broader audiences in the frontcountry for longer periods and to offer more accessible and condensed experiences of park resources and values."

Part of the plan calls for expansion of the trail system around the lodge, restorations to the historic lodge, and new visitor-oriented upgrades.

Lastly, there's the Beach Trail, which covers about a mile. The long stretch of shoreline south of the cove's dock allows for a pleasant stroll. Low tide reveals a myriad of intertidal life. It’s a terrific place to see land, shore, and sea birds.

The plan also calls for improving the hiking experience around Bartlett Cove, in part by creating and maintaining "quality viewscapes from land to water in key trail locations that interpret the post-glacial changing landscape and park resources. Add benches where appropriate, and design with wide spots for group gathering and other approaches that focus pedestrian traffic to reduce social trailing."

New trails also are called for in the document.

A new approach to bay excursions also is envisioned "to provide leisurely, sensory-focused boat tours for whale and wildlife watching that are 1/2 day or shorter, and focus on understanding the science of productivity in lower Glacier Bay." More kayak rental opportunities at Bartlett Cove, as well as paddleboard rentals, also were being considered, but away from the historic district.

"Those facilities and trails that were associated with that plan, we were all very hopeful about, and we had the funding for it," Hooge said. "Those will have to be delayed. We’re taking a very cautious approach now."

At the National Parks Conservation Association, Alaska Regional Director Jim Adams called the financial hit extremely unfortunate.

“Glacier Bay National Park needs funding to protect its world-famous resources and educate visitors. Without that funding, basic things like a needed patrol and research boat and front country planning and trail construction to attract independent visitors will go away," Adams said in an email. "But with proper funding, Glacier Bay can attract visitors, provide employment, and provide markets that help the gateway community of Gustavus move ahead through these hard times.”

Gustavus is being particularly hard hit by the tourism loss, as Traveler's Lynn Riddick noted in a story last month.

"Glacier Bay is very hard hit by this, but also the community is intimately tied to tourism. The Park Service has been a big part of this. We’ve helped to try to move people from commercial fishing in the park to various tourism-related businesses," said Hooge. "So there’s going to be great suffering in this community, financially.

“I dealt with a lot of phone calls from some very sad people seeing the potential for their business completely failing. That’s definitely hard," he added.

The park's Bartlett Cove area is vastly underused/Kurt Repanshek file

Bartlett Cove locator photo/NPS

Typically, Hooge hires 65-70 seasonal workers to supplement his roughly 65 year-round employees. While this year he has drastically cut back his summer hiring to a skeleton staff of about 10, he's hoping to hold onto his permanent employees who call Gustavus home year-round.

"God forbid we had to RIF (reduction in force) large numbers of permanent employees,' said Hooge. "It would be absolutely devastating to the community.”

Comments

How does Glacier get around the requirment that user fees have to be used primarily for capital projects? It would seem if they are 70% of their total budget, they are providing substantial operating funds.

Glacier Bay has specific legislative authority to use 60% of funds received as base for marine related activities, the remaining 40% is treated the same as other parks franchise fees.