A fire burns in Squamish, B.C. on April 16, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Felix McEachran Mandatory CreditEdward Struzik, Queen's University, Ontario

A fire burns in Squamish, B.C. on April 16, 2020. THE CANADIAN PRESS/HO-Felix McEachran Mandatory CreditEdward Struzik, Queen's University, Ontario

In the summer of 2003, I had a first-hand look at a fire season that was unlike any that had occurred before.

Thousands of acres were burning in Western Canada, prompting officials to call in more people to help suppress the fires. They piled into crowded tent camps and other makeshift facilities. Approximately 45,000 people were evacuated to nearby towns, hotels and community centres for days and sometimes weeks. Hundreds of emergency relief responders came in close contact.

If the coronavirus pandemic persists this summer, Canadian agencies will be hard-pressed to deal with a fire situation like that one, according to several provincial and federal officials, who spoke on the condition their names would not be used because they were not authorized to publicly discuss their work. Canada is unprepared for an intense wildfire season.

Unstable funding, the need for social distancing and the likelihood that neither the United States nor any other country will offer a helping hand when our resources are tapped all raise the potential for a nightmarish scenario.

The ‘Holy Shit Fire’ of 2003

The 2003 fire season wasn’t notable for the area burned, but for the fact that so many towns, national parks, industries and historic sites were in harm’s way.

People watch as flames approach houses in Kelowna, B.C., on Aug. 22, 2003. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Rich Lam

People watch as flames approach houses in Kelowna, B.C., on Aug. 22, 2003. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Rich Lam

More than, 2,000 people evacuated the Crowsnest Pass region in southern Alberta. Waterton Lakes National Park was on standby for an evacuation as 13 per cent of neighbouring Glacier National Park in Montana burned. A prescribed fire in Jasper, Alta., got out of control and might have torched a 20 kilometre-long path to Hinton had it not been for the heroic efforts of Parks Canada wildfire managers, who dropped fuel on the forest to force the fire to turn on itself.

Banff was threatened on two fronts. The first came from an out-of-control prescribed burn that ignited east of the town, near Canmore; the second from an enormous fire that was chugging east along the mountain highway that runs through Kootenay National Park into Banff. It was called the “Holy Shit Fire” because that’s how everyone reacted when they saw it from a helicopter.

Wood Buffalo, Mt. Revelstoke and Prince Albert national parks also burned in the weeks before the interior of British Columbia lit up around towns and cities, including Kamloops and Kelowna. The military was brought in and triaging became the order of the day.

Dens destroyed

Mark Heathcott also remembers the 2003 wildfire season well because he was Parks Canada’s fire management coordinator for Western Canada. At one point, he was asked to send resources he didn’t have into polar bear country to prevent a fire from burning the Prince of Wales historic site near the west coast of Hudson Bay. The building survived, but several polar bear dens in Wapusk National Park were destroyed.

Typically, Heathcott would have been able get support from the provinces or U.S. firefighters, but the competition for resources was fierce that summer. He and his colleagues were lucky because Nik Lopoukhine, the director general of Parks Canada, understood fire. He signed off on an emergency response plan in the spring when Heathcott warned him that an intense fire season was likely. Lopoukhine’s directive compelled superintendents from across Canada to send employees to help suppress fires that might get out of control.

Minimal travel, no help

Like many wildfire managers in North America, Heathcott wonders how various agencies are going to respond if the coronavirus persists into what is forecast to be an extreme fire season.

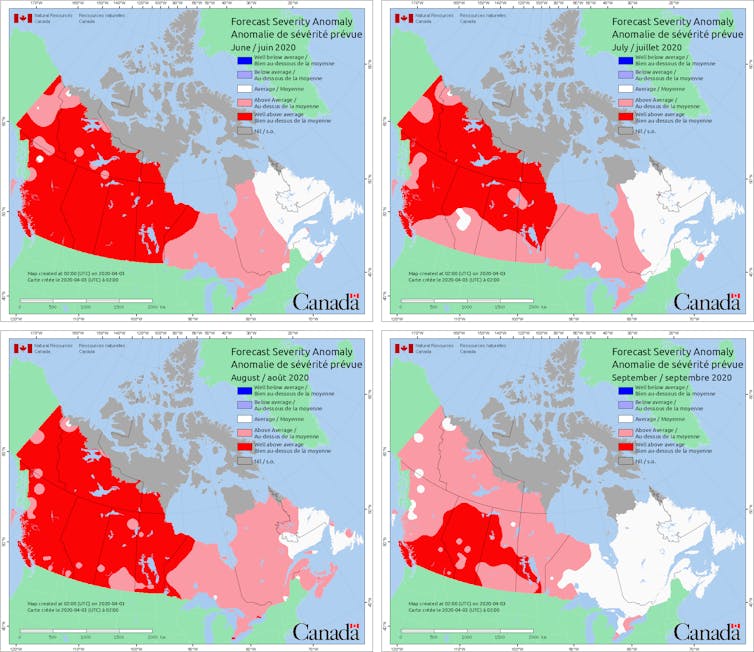

The Forecast Severity Anomaly shows which regions are predicted to be above or below the regional climate average. (Canadian Wildland Fire Information System)

The Forecast Severity Anomaly shows which regions are predicted to be above or below the regional climate average. (Canadian Wildland Fire Information System)

Last fall, Alberta ordered budget cuts of $23 million that included closing 30 wildfire lookout towers and shutting down a helitack program of firefighters trained to rappel into a wildfire. The government has since found $5 million to hire 200 more firefighters.

In early April, Victoria Christiansen, who heads the U.S. Forest Service, laid out some broad guidelines, including a recommendation that firefighters be deployed in ways that minimize travel to other geographic areas. This is bound to result in our American friends denying or limiting our requests for help.

Christiansen is also recommending social distancing, which is almost impossible to do in the tent camps typically used by firefighters in Canada. She’s calling for more seasonal employees to be hired, without admitting that this may not be possible without additional financial support, and with a workforce that might be reluctant to take on an already dangerous job in which they could be quarantined for up to month before and after a fire.

Heathcott voiced the concern of others I talked to when he noted that it will difficult to mount the usual attack. “Perhaps the crews will be dispersed, ‘coyote camping’ in small units, spotted out along the fireline, walking in on the fires,” he said.

“This may occur anyway, as the Canadian fleet of helicopters may already be decimated with the loss of revenue from the early end to heli-skiing and the lack of winter seismic work.”

A helicopter drops water on the Getty Fire in Mandeville Canyon, in Los Angeles, on Oct. 28, 2019. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

A helicopter drops water on the Getty Fire in Mandeville Canyon, in Los Angeles, on Oct. 28, 2019. (AP Photo/Marcio Jose Sanchez)

Even if contract helicopters remain available, he wonders, how does one social distance in the compact cabins and tents? “We will see increased competition for the resource, and more fires may be lost at initial attack. With a reduction of air support, crews may be exposed to increased danger on the fireline and we may see increased work refusals, gun-shy fire managers and more let-burn situations. Forget about inter-agency deployments, everyone will be hunkering down on their own turf.”

The high cost of not being prepared

One of the many things the coronavirus pandemic has taught us is that being unprepared for emergencies comes at a high price. Dealing with the pandemic is a challenge because there is not enough robust data available to inform us how we can get back to some semblance of normalcy.

That’s not the case with wildfire.

Since 2003, wildfires have been burning bigger, more often and in increasingly unpredictable ways. Projected increases in area burned suggest the current state of wildfire management in Canada will be unable to cope with increasing wildfire activity. Restricting people from going into the backcountry, as some provinces are now doing, will help but not solve the problem.

There is a vaccine of sorts that could minimize the risks wildfires pose to human health and safety. The latest blueprint for that comes courtesy of the Canadian Forest Service.

Instead of investing more, however, we have been spending less. Unless that changes, our response to a wildfire season like the one in 2003 may end up being as chaotic and scary as the ongoing response to the coronavirus pandemic.

Edward Struzik is the author of “Firestorm, How Wildfire Will Shape Our Future.”

![]()

Edward Struzik, Fellow, Queen's Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy, School of Policy Studies, Queen's University, Ontario

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

The majority of wildland firefighters are healthy young men and some women. Statisticly this group has experienced an infintesimal percentage of those infected and even smaller percentage of those dying. Their risk is likely to be far higher from the fire than the virus.

Ever spent three weeks in a wildland fire camp Buck? How did you become an expert on this topic too - perhaps it was when you were studying epidemiology?

The notion that the young are somehow less likely to contract coronavirus has been repeatly debunked but that likely doesn't get reported on the news feeds you follow. Emerging data now also shows an alarming number of strokes occuring in the young. Your breadth of knowledge on every topic every time is about as credible as the President's. None of the science-based guidance claims that young people can or should ignore the precautions to coronavirus. Please provide some evidence that only an "infintestimal percentage" of those infected come from young folks? We cannot draw scientific conclusions without sufficient data to do so - no matter how much we want may want to.

https://www.webmd.com/lung/news/20200326/young-people-far-from-immune-to...

I don't know that any one has claimed the young are less likely to contract coronavirus but the statistics are quite clear they are less likely to develop symptoms, be hospitalized or die.

Take NY for example: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2020/04/07/new-york-coronavir...

85% of those that died had one more preexisting conditions such as obesity, heart failure or hypertension. Not what you find in most your front line wildland fire fighters. Furthermore only 7% of the deaths were people under the age of 49 and the percentage drops sharply from there as age drops. Again not many 50+ that are fighting the fires. These patterns, according to my news feeds like the CDC, are consistent across the country and across the world.

You don't have to be an epidemiologist to understand statistics.

I've been a wildland firefighter (WLFF) unlike some. This article is about Canada which already has a much more capital-intensive firefighting regime with smaller human crews (even if they almost exclusive camp rather than hotel up) per incident and many more choppers, VLATs, dozers, engines, etc. Canada's WLFF doctrine also draws much, much bigger boxes. All of which are big duhs, when you consider total acreage and population. If the Canadians are rethinking their approach and developing serious contingency plans, that's a BFD.

Maybe the earliest commenter didn't actually read the article based on his tepid take.

Sorry Irony, if they rely more on capital equipment than humans, that would seem to reinforce my comment, not contradict it.

Now I'm sure that you didn't read it since fatality rate wasn't directly discussed, so why post about it? Unlike all those lines that the article spent on already settled topics such as the USFS being unlikely to send aid or the effects on evacuation orders for residents (fires affect more people than young, fit WLFFs). Also, your inability to read means that you can't comment on the already baked-in effects of provincial budget cuts to fire programs (despite federal recommendations to the contrary) or how this has unknown effects on heli availability.

I think you should call up Mark Heathcott or Ed Struzik and see how seriously they take you hammering home your "point." If a long distance call to Canada is too much trouble, Colorado Firecamp is in only Salida. Why don't you go visit them and tell them that they shouldn't be thinking about how to adapt to the already disrupted training season because the fatality rate could only double among deployed crews?

Irony, the aspect of the article I was addressing was about the risk of corona virus to firefighter camps. I didn't address budget cuts because that wasn't the subject of the article. I was specifically addressing the issue related to firefighters in firefighter camps. You have problems otherwise with the situation, go for it.