A seismic line created by a 33-ton vibroseis vehicle through Big Cypress National Preserve/Quest Ecology

Traveler Special Report: Threatened And Endangered Parks

Myriad Threats Assault The Essence Of America’s Best Idea

By Kurt Repanshek

National park units in the lower 48 states are being confronted, and in some cases overrun, by issues ranging from climate change and invasive species to energy exploration and overcrowding. Natural and cultural resources are being harshly impacted, and in the case of invasive species in South Florida, some native species are being wiped out.

These impacts are not the usual park stresses at the road-paving or conservation-fencing level that can be addressed by maintenance or policy tweaks. What the National Park System faces is the prospect of transformative, even irreversible, change due to human-caused impacts, whether direct -- such as overcrowding -- or, as in the case of climate change, the result of policy and political failures.

Big Cypress National Preserve in South Florida just might be the National Park System’s poster child for what constitutes an endangered park. While so-called thumper trucks, 33-ton mechanical beasts that shake the earth in search of oil reserves, tear up the preserve’s landscape, invading Burmese pythons slither through this sub-tropical landscape, feasting on its native animals, including the occasional alligator. All the while, sea level rise is slowly, quietly, and largely unnoticeably, poisoning the park’s namesake trees with salty groundwater.

Cape Lookout National Seashore on North Carolina's Outer Banks wouldn’t be out of place on that poster. Hurricane Dorian in September sliced up the seashore’s barrier islands like a hot knife going through butter. Meanwhile, the possibility of a commercial spaceport arising just four or five miles west of Cumberland Island National Seashore in Georgia poses the threat of a dozen rocket launches a year that figure to impact the sublime national seashore in ways ranging from inconvenient to disastrous.

In this, National Parks Traveler’s first annual Endangered And Threatened Parks project, we take a look at those landscapes that are struggling to retain the qualities that led to their inclusion in the National Park System in the first place.

Parks we've called out face exceptional problems that affect their natural resource health as well as the visitor experience. Failure to come up with, fund, and implement management plans to counter these impacts will lead to continued deterioration of individual parks and to the National Park System as a whole.

Three years after the nation celebrated the 100th birthday of the National Park Service, it seems like a grand dose of hyperbole to suggest that the National Park System is seriously in danger of becoming a fond relic of conservation and national introspection. In years past it has been argued by some that we shouldn’t place national parks in jars figuratively to protect them from outside influences. Today, though, it might be necessary if we’re to save many of these unique settings that justified their inclusion in the park system in the first place.

“Preservation is about deciding what's important, figuring out how to protect it, and passing along an appreciation for what was saved to the next generation,” reads one page within the National Park Service’s massive web domain.

That goal seems more elusive than ever before for some units of the park system, as there are many threats and impacts pressing on parks today:

- Climate change is redrawing the settings of many parks, as Rita Beamish’s article below on parks in Alaska soberly demonstrates.

- Air pollution is marring vistas at Sequoia National Park and at times threatening the health of visitors as well as vegetation in places such as Acadia National Park, Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, while also impairing fisheries in other parks through acid deposition.

- Invasive species, from pythons and feral hogs to mongooses and tiny mussels are fouling park landscapes and waters in places such as Big Cypress National Preserve, Big Thicket National Preserve, Virgin Islands National Park, and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

- Visitors are impacting parks, and not just by trampling vegetation and creating social trails but by overwhelming staff in these times of reduced workforce and diminished funding.

“We’re seeing the impacts of climate change unfold on almost a daily basis now. Things that we didn’t fully anticipate 10 or 20 years ago are now becoming some of the biggest threats our national parks are facing today,” Mark Wenzler, the senior vice president for conservation programs at the National Parks Conservation Association, told me as we discussed Traveler’s effort to profile the myriad threats to the National Park System.

Traveler's Endangered and Threatened Parks is not intended to be a definitive list of parks whose natural, cultural, or historic resources are in grave danger from introduced impacts. Rather, it's intended to provide an overview of the threats that are jeopardizing the integrity of the park system.

Many national park sites in Alaska, which holds more than half the 85 million acres of the entire 419-unit National Park System, very well could be categorized as “endangered” due to climate change impacts. Our coverage of this issue begins with a look at the situation in Alaska, followed by additional endangered and threatened parks in the system.

Continued retreat of tidewater glaciers at Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve could force park staff to choose between protecting Johns Hopkins Bay for seal pupping or to open more of it up for cruise ships./Kurt Repanshek file

Hot Times in the North

By Rita Beamish

Editor’s note: As delegates from nearly 200 countries gathered for the recent international conference on climate change, U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres decried the “utterly inadequate” global response to the crisis so far. He warned that the “point of no return is no longer over the horizon” but that “It is in sight and hurtling toward us.”

Nowhere are the consequences more visibly “hurtling,” and landing, than in Alaska. And in the northern state’s national parks and preserves, that means growing pressures on the very resources the National Park Service is charged with protecting.

When Jeanette Koelsch was a kid in Nome, Alaska, her clown makeup froze on her face as she traipsed through the cold in an oversized Halloween costume she’d wrestled over her bulky snowsuit.

“Now, when I take my son trick or treating, it often rains. He can wear a sweater and rubber boots,” says Koelsch, superintendent of Bering Land Bridge National Preserve. She references what everyone knows: Alaska is a lot hotter than it used to be, its temperature rising twice as fast as the warming globe’s average increase since the mid-1900s.

The scary specters worrying Koelsch these days thus have nothing to do with Halloween. They center on rapidly eroding coastlines washing away archaeological artifacts, vanquishing the chance to learn from them and honor their history; habitat changes upending wildlife patterns; shorter snow seasons and melting sea ice hindering subsistence practices that have sustained native cultures for thousands of years.

These shifts affect the very cultural, natural, and subsistence resources that Bering Land Bridge -- and its neighbor to the north, Cape Krusenstern National Monument – were established to protect. And it’s a dynamic playing out in national parks across Alaska. Treasured lands, waters, and cultural resources that the federal government vowed to protect for future generations are being altered and even destroyed by the warming planet.

Change is both subtle and dramatic: from the global-warming poster children -- melting glaciers -- to marine life shifts that ripple up the food chain. Lifeless seabirds by the thousands have washed up along the coasts, while other species are appearing where they’ve not previously been seen. Change happens as fast as the crash of a calving glacier, and as gradual as the vegetation shifts when ice-rich permafrost thaws into soupy mush. It’s happening now, and it’s speeding up.

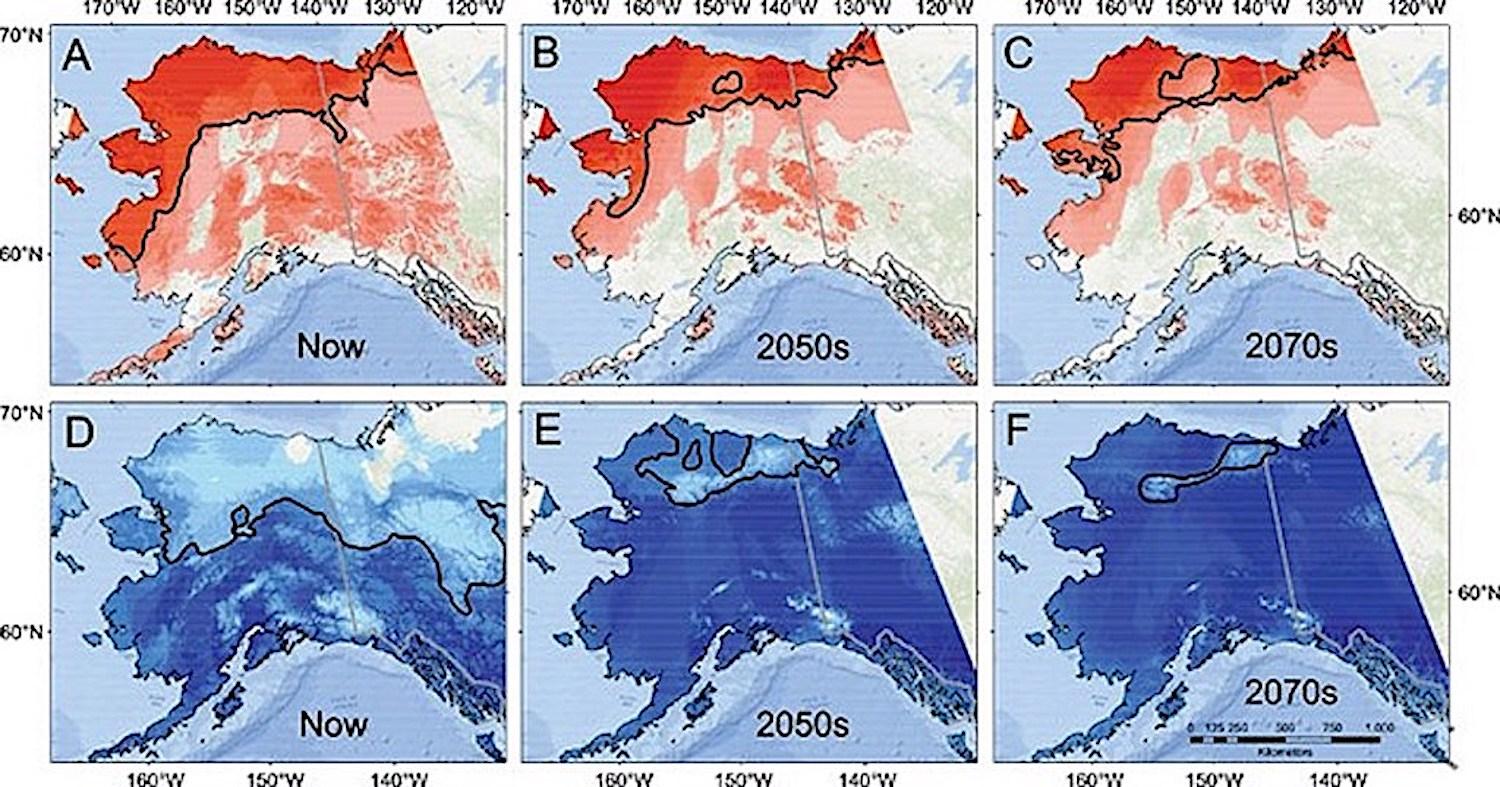

Climate envelope model predictions for tundra (top; red) & forest taxa (bottom; blue) based on (A) and (D) current (Now), (B) and (E) 2050s, and (C) and (F) 2070s climate projections. The color gradient reflects areas of low (light) to high (dark) diversity. Distribution of diversity reflects compilation of predictive maps for 12 boreal and 7 tundra/alpine-associated species. Black lines provide a guideline to the extent of ≥50% of the diversity within boreal and tundra biomes./NPS

National Park Service scientists are tracking all of this – counting bird carcasses, measuring glaciers, monitoring caribou movements, and studying fish patterns -- to nail down impacts in Alaska parks and determine how, or if, they can adapt to climate change. Teasing out “normal” dynamic fluctuations in the volatile Alaska wilds is part of the challenge of illuminating whether anomalies in the record-breaking 2019 summer heatwave are a window into the future hot North.

“For us, things are going so quickly,” said Koelsch, noting the big-picture challenge: “How does the Park Service adapt to these issues in a way that mitigates impacts, that provides for access, that preserves subsistence and cultural resources, and protect natural resources?”

The question is only becoming more pressing. Just a partial litany of what Park Service scientists are tracking hints at the magnitude of change in these cherished – and environmentally crucial -- lands and waters:

- In Arctic national parks, lakes are draining as thawing of frozen ground opens new channels, with vast ecosystem implications. In 2005-07 and in 2018 following exceedingly warm years, dry-ups included six large Bering lakes that were habitat for the rare yellow-billed loon, scientists report. Barren mudflats, bereft of loons, remained.

- The virtual disappearance of the Bering Sea’s “cold pool” has shifted fish distribution. Snowcrab biomass was reported down 45 percent 2010-2018, while Pacific cod and pollock, more typical in warmer waters, increased in the area, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

- At Cape Krusenstern, evidence of more than 5,000 years of human occupation – house remains, tools, animal bones -- is slipping into the sea as frozen bluffs thaw, protective sea ice declines, and battering storms take their toll, undercutting the park’s mission to preserve and interpret this archaeological record and protect Arctic ecosystems and subsistence resources.

- Sea stars, a vital predator species that keeps nearshore organisms in check, have plummeted in number since 2014, including along the coasts of Kenai Fjords and Katmai national parks. The virus-caused “wasting” epidemic has coincided with warming coastal waters, although scientists have not nailed down the specific triggers in the web of pathogens and environmental stressors..

- Ocean acidification fed by carbon dioxide absorption has pushed Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve to the “threshold of fundamental ecosystem changes,” its superintendent says. Acidification damages shellfish crucial to the marine ecosystem by making it difficult for them to grow their protective shells.

- NOAA scientists have identified a huge new “blob,” recalling the destructive 2014–2016 marine heatwave that caused massive marine die-offs and toxic algal bloom proliferation.

- Melting sea ice measured at a record Bering Sea low in 2018, about 10 percent of normal, and 2019 is nearly as low. NOAA made an “unusual mortality” declaration for ice seals when 282 dead seals were found between June 2018 and September 2019 in the Bering and Chukchi seas, five times the average and a concern for native people who rely on the marine mammals for food, clothes, and subsistence culture.

- Even human waste on the continent’s highest summit -- tons and tons of it -- is affected by warming. Deposited by Mount Denali climbers and frozen for decades in the ice, the old poop is making its way, over time and via glacial melt, to the downstream watershed. The Park Service these days requires climbers to carry poop cans in and out, but melt is expected to flush out the old waste in the coming decades.

Big Hungry

In the shadow of Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve’s icy wonder, the bears drifted into the tiny gateway community of Gustavus this past summer. Not just the usual one or two, but 14 of them in a matter of weeks -- skinny, hungry, rummaging in gardens and casing chicken coops.

“They had no body fat,” explained Glacier Bay Superintendent Philip Hooge. In a record hot and dry summer, the bears’ salmon diet was elusive. Streams in the cold rainforest environment warmed – bad for salmon survival due to insufficient dissolved oxygen – and without the area’s typical rains and drizzle, some waterways were barely flowing, he said.

“I’ve been here 25 years. The number of clear days we’ve had – I’ve never seen anything like this,” Hooge said as the trend continued into September, dry months compounding the worrisome march of warming.

So while travelers -- visiting at a rate of 600,000 cruise ship passengers a year -- gloried in sunny, clear-sky views of Glacier Bay’s icy cliffs and crashing ice chunks, Gustavus residents worried about their shallow wells drying up.

And the fires that swept Alaska with unusual ferocity this year sparked what-if concerns, though they did not reach Glacier Bay. “We’ve never burned here,” Hooge said. “This is not a fire-adapted landscape.”

Rivers of Ice

Glacier Bay’s park mission includes ensuring access to tidewater glaciers, dynamic rivers of ice that terminate in tidal bodies. Scott Gende, Glacier Bay senior science advisor, posits that shrinkage by some tidewater glaciers ultimately could increase visitor pressure on Johns Hopkins Glacier, where protecting an important pupping site for seals is so vital that the park already restricts a disturbing influence, cruise ships, there.

“The conflict between resource protection and the mandate to allow visitor experience comes more to the forefront,” Gende said, adding, “Ten years ago this was not even on the radar screen.”

Will climate change force the Park Service to choose between visitor enjoyment -- cruise ships at Glacier Bay National Park -- or natural resources protection?/Kurt Repanshek file

Distinct from tidewater glaciers, Alaska’s sprawling land-terminating glaciers are a key climate change barometer. Two-thirds of all ice-covered areas in Alaska national parks are in massive Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve -- glaciers as thick as 3,000 feet and as big as the state of Rhode Island.

In Kenai Fjords National Park, where icefield coverage is the size of Los Angeles, Exit Glacier’s retreat continues to offer a front-row seat to climate change – but visitors must walk increasingly further to see it. Its retreat rate more than quadrupled, averaging 191 feet a year from 2013 to 2018, compared to its 1815-2018 rate, park measurements show. Now recessed 1.67 miles overall, it’s no longer visible from the viewing pavilion, hemmed by a sea of trees and shrubs where the vast glacier once sprawled. Extending the walking path over the years, the park makes access a priority.

“What makes it so iconic is that because of the access, people observe the change itself. They don’t have to look at data,” said Deb Kurtz, the park’s physical science program manager.

Michael Loso, a Wrangell-St. Elias park geologist who savors his office view of majestic, ice-locked Mount Blackburn, says glaciers will cling to very cold, high mountains for hundreds of years in places like this. But the rapid melt is “way more than you would expect” in normal glacial retreat-and-advance dynamics, and affects all plants and animals in ways not yet fully understood.

“Watching the glaciers shrink, it really … strikes at what to some people is the heart of what the park is about,” Loso said. When climate analysis looks to distant future outcomes, he adds, “A big part of the message here is that it’s happening.”

Short-tailed shearwaters, Ikpek Lagoon, Bering Land Bridge National Preserve./NPS, Jason Tucker

Species in Trouble

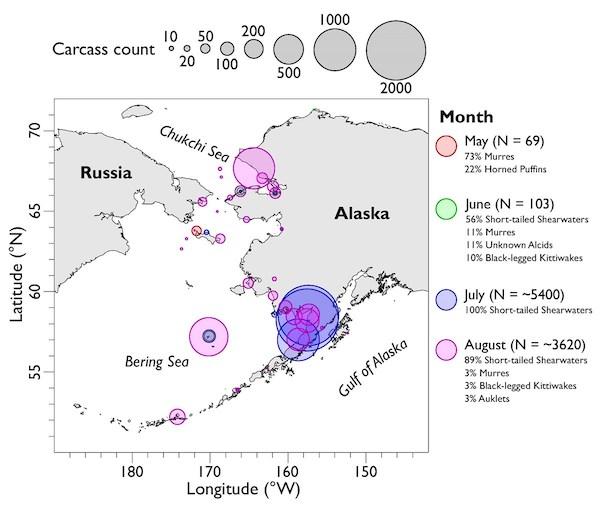

A disturbing report reached NPS marine ecologist Heather Coletti in 2015. A retired government biologist had come upon a startling sight: an estimated 8,000 bird carcasses on the shores of Prince William Sound. It turned out to be a die-off across the north Pacific, coinciding with warmer waters and “unprecedented in its scale, spatially and numerically,” Coletti said.

Each year since, massive seabird die-offs have triggered alarm in Alaska and Russia, including along national park coasts from Cape Krusenstern to Katmai, Kenai Fjords, and Glacier Bay: murres, puffins, shearwaters, auklets, and kittiwakes are all part of the toll. Especially troubling is that these birds are indicators of ocean health.

“We have known these systems are changing, but it was such a drastic response and so widespread -- it’s a bit frightening,” Coletti said.

Tests reveal starvation as the culprit. “Why they are starving is the next question,” she said. “There are likely lots of drivers at play”: Prey fish are known to grow less in warmer waters and thus may not meet birds’ caloric needs; warming waters may drive away cold-water fish they eat; large fish with metabolisms raised by warmer water might outcompete birds for the prey; birds may be exposed to biotoxins from algal blooms thriving in warmer water.

“Everybody recognizes that interconnectedness,” said Coletti. “It’s not like it’s hot and then they die. It’s lots of shifts in the food web.”

Counts of seabird mortalities across Alaska from May - August 2019./Map provided by Coastal Observation Seabird Survey Team coasst.org

In the intertidal zones, her research finds “potentially cascading community level effects” in warming waters of Prince William Sound and off Kenai Fjords National Park, Kachemak Bay, and Katmai National Park. Small mussels are declining with the loss of their algae habitat, while large mussel density has increased with the devastation of their sea star predators. Ripple effects likely will extend to species like sea otters and ducks.

Fish in warming lakes and streams are struggling, too. Large numbers of salmon died en route to Alaska spawning grounds in 2019 as water temperatures soared beyond 70 degrees Fahrenheit, well above the preferred 45-to-55 degree range.

“Salmon die-offs were not reported within national park boundaries,” noted NPS aquatic ecologist Krista Bartz, “but they were observed nearby, from Bering Land Bridge National Preserve to Kenai Fjords.”

Alaska parks did see die-offs of other fish, such as northern pike, during the heatwave, as well as delays during this year’s heatwave in the upstream salmon migration – a problem that affects not just spawning salmon but also species that rely on them for food.

"It’s hard to know how it’s going to pan out in the end because it’s very complicated,” with unknowns about how warming will change the local salmon population habitats, Bartz said.

Slippage Underfoot

In Denali National Park, the workhorse, 92-mile road that each year carries hundreds of thousands of tourists took a drubbing last summer at Polychrome Pass, in the benignly named Pretty Rocks area. Some 300 visitors traveling in 17 buses were stranded temporarily when a cascade of mud and rock blocked the steep mountainside roadway, slippage spurred by the wettest summer in 95 years of record, park scientists say, on top of a continuing destabilization as the underlying permafrost thaws.

Permafrost – permanently frozen ground -- underlies nearly 40 million acres of national park lands in Alaska, about the size of Florida, notably in the five Arctic parks and in Wrangell St.-Elias, as well as in Denali. Warming is expected to reduce Denali’s near-surface permafrost over the next half century to 6 percent of the park’s area, from the current 51 percent, according to Park Service and University of Alaska researchers.

Of some 150 unstable sites on the Park Road, Pretty Rocks is the “problem child,” relentlessly encroaching even after it’s shored up, said park geologist Denny Capps. Its movement reached two inches a day as of this fall, overlapping “a very high-ranking, debris flow and rockfall hazard,” he said.

“If the situation continues to worsen, eventually we will not be able to maintain the road at this location without major engineering solutions” -- whether rerouting, installing a bridge, or blasting the area, solutions that all have their political, financial, and environmental problems, he said. The park has yet to decide on a long-term solution, but it is stepping up planning, monitoring, and maintenance for the coming year.

Denali staff collecting GPS data at the Pretty Rocks landslide near mile 45 of the Park Road on March 22, 2019. The survey rod she is holding, 6.5 feet tall, is placed near centerline of the road and shows the amount of displacement since September 14, 2018./NPS, Denny Capps

Denali isn’t alone with permafrost problems. Melting of this thick layer of frozen earth is creating slumping and sliding in places such as Noatak National Preserve and Gates of the Arctic National Park. The result has left thousands of deep depressions and slope failures, which then release greenhouse gases that had been locked in the ice for centuries. Park habitat is further altered as lakes draining through channels created by the slumping send sediment and siltation into other water bodies.

Populations at the Forefront

Alaska’s subsistence populations are living it all first-hand.

“We are already at a critical juncture of sea ice loss that already has started a cascading effect on fish and wildlife,” increasing hunters’ travel distances for ice-dependent mammals, Kawerak, a Bering Strait-region tribal consortium, wrote to the Senate Indian Affairs Committee on September 9.

Eighty-six percent of native villages are threatened by flooding and erosion, a 2003 U.S. General Accounting Office report found. Roads buckle, power poles sink in softened earth and structures topple as permafrost ground goes gelatinous. With protective sea ice forming later in the year, village coastlines are left susceptible to the increasing ferocity of pounding waves and storm surges. Entire villages are working on relocation in the face of inundation.

Escalating ship and tanker traffic through newly navigable Arctic waters has heightened worries about pollution, oil seepage, and ships striking marine mammals or impacting them with engine noise.

“Our carbon footprint is so very small but we’re feeling the impact of climate change by a factor of two – twice as many impacts as the folks in the lower 49,” said Austin Ahmasuk, marine advocate for Kawerak. “Impacting our food security, it’s transforming who we are … We’re seeing all these things they said would happen in 2050 -- they are happening now.”

The temperature values indicate presence of near-surface permafrost. The red color identifies areas with Talik (i.e., unfrozen ground above permafrost).

Noting the Arctic’s particular sensitivity to warming, Jon Jarvis, former head of the Park Service who was once superintendent of Wrangell-St. Elias, said unprecedented impacts like fires of unparalleled size and intensity are evident in Alaska and transforming the landscape. For instance, he said, “You can see the climate changes as forests spread and become established over these areas of melting permafrost and receding glaciers.”

Old paradigms of park management will need to change, Jarvis told the Traveler. Aside from carbon-emission reduction, he said, the Park Service must double-down on broad strategic management that starts with scientific and traditional knowledge and includes public education.

With ecosystems changing in ways not yet fully understood, “You can only do so much,” for strict conservation, he added. “We are left with adaptation. We still have a mission, and it’s for future generations. If we want to maintain the parks in as unimpaired a status as we can … we have to be smarter, use science and use the best strategies -- some at landscape scale, some protecting refugia … even some assisted migration to allow some species to survive,” he said. “In some cases, we may have to say goodbye.

“The parks will still be there. It’s just they will be different.”

* * * * *

Endangered And Threatened Units Of The National Park System

By Kurt Repanshek

A commercial "spaceport" proposed to be built just west of Cumberland Island National Seashore would send rockets over the seashore and its wilderness/NPS file

For flora and fauna, being listed under the protections of the Endangered Species Act marks a realization that they are at risk of being wiped off the Earth, and prompts efforts to remove the obstacles to their survival.

Certainly, national parks cited by the Traveler as being threatened or endangered does not reflect that they are in danger of “going extinct.” But the risks confronting them do present the potential for greatly affecting the very reasons they were added to the park system.

"We need a more dedicated effort to resolving and identifying these issues and understanding this world that we live on," said Phil Francis, chair of the Coalition to Protect America's National Parks. "I think (we need to) aggressively manage, adaptively manage these parks so that we can better anticipate change and react to the change.

"I know in the Smokies, which is not far from where I live, they found an armadillo on Highway 441 going through the park," he added. "I don’t know if that armadillo hopped on an RV and came up from Florida for a vacation, but they found one in the park. So it makes me think of the Everglades and Big Cypress and the pythons. What else are we going to have?

"We have a lot of invasive species in many parks already. So what happens when these ecosystems begin to change, what can we really do about it. I'm afraid I don’t have the answers, but I know that we should put some of our best minds together and really think about this and examine our strategies and policies to make sure they’re all in alignment so that we have a chance to protect and preserve these parks for future generations.”

One thing out of the Park Service's control, said NPCA's Wenzler, is climate change and the role it plays in allowing non-native species to invade the parks.

"It’s an interesting problem, because on the one hand there are some things the National Park Service can do with more funding, with better management. But there’s also a global problem that they can’t deal with, that’s climate change," he said. "Much of the spread of invasive species is being driven by factors far outside the Park Service’s control.”

Sea level rise and more potent hurricanes also are aspects of climate change that practically tie the Park Service's hands, added Francis.

"I think it’s almost an impossible situation to be in. You’ll never have enough money to restore all those roads in a timely way," he said, referring to the storm damage done to North Carolina 12, the road that runs the length of Cape Hatteras on the Outer Banks. "Throw Gulf Islands (National Seashore) into that mix, too. I mean, look how many times their highway has washed away over the years. It’s not going to get any better for them. And then the heavy rains up in the mountains of North Carolina, the Blue Ridge Parkway had sections of road that are washing away. It’s $3 million-$5 million to fix it every time it happens. So, the managers are going to have declining staffs, less resources, increased pressure from the tourism economy, and so to try to manage those priorities will be enormously difficult.”

The question is whether, and how, do we turn the clock back or protect these landscapes and their resources?

“I think there are some impacts that can last multiple generations. So it’s really a question of timescale,” Wenzler replied when posed with that question. “Look at the oil and gas development that’s happening throughout the West. It’s an incredible pace that’s happening around many national parks. Those leases can be in place for decades. They can be renewed very easily, that land is then off the table for conservation purposes.

“It may feel like forever if you’re talking about two or three generations. Other impacts, perhaps we can solve a little more quickly,” he said. “It’s really kind of a mixed bag of timescale of how these impacts can be addressed, and which ones are irreversible or not.”

Endangered National Parks

Oil exploration. Sea-level rise. Diminished air quality. Overcrowding. Each poses a threat to national parks. The following parks face the most significant threats to their mission.

Climate Change

Glacier National Park, Montana

The warming climate is melting the park's iconic glaciers, whose loss would impact not only the appearance of Glacier but also affect watersheds, vegetation, and wildlife. In 1850 the park had about 150 glaciers; by 2015, the number had plunged to 26, and they are expected to vanish before the end of the century.

Joshua Tree National Park, California

The warming climate also is adversely impacting Joshua Tree, where it one day could become too warm for the park's namesake trees to grow within its boundaries. Researchers say that under the best-case scenario of slowing climate change, 19 percent of the tree habitat in the park would remain after the year 2070. In the worst case, with no reduction in carbon emissions, the park would retain a mere 0.02 percent of its Joshua tree habitat, they say.

Up Close: Glacier National Park

Science is not a static pursuit, as changing conditions, technologies, and interpretations can alter what we previously thought was true. That was the case at Glacier National Park in the summer of 2019, when the removal of interpretive placards predicting the demise of the park’s rivers of ice in 2020 sparked allegations that the National Park Service had made up a climate change scenario.

But the controversy didn’t change the National Park Service’s position that the glaciers are shrinking and “there is absolutely no disagreement in the scientific community that they will disappear in the not-too-distant future.”

The dispute revolved around interpretive exhibits that stemmed from research in “the late 2000s” that showed the park’s Blackfoot and Jackson glaciers melting more quickly than had been predicted in 2003 research by the U.S. Geological Survey.

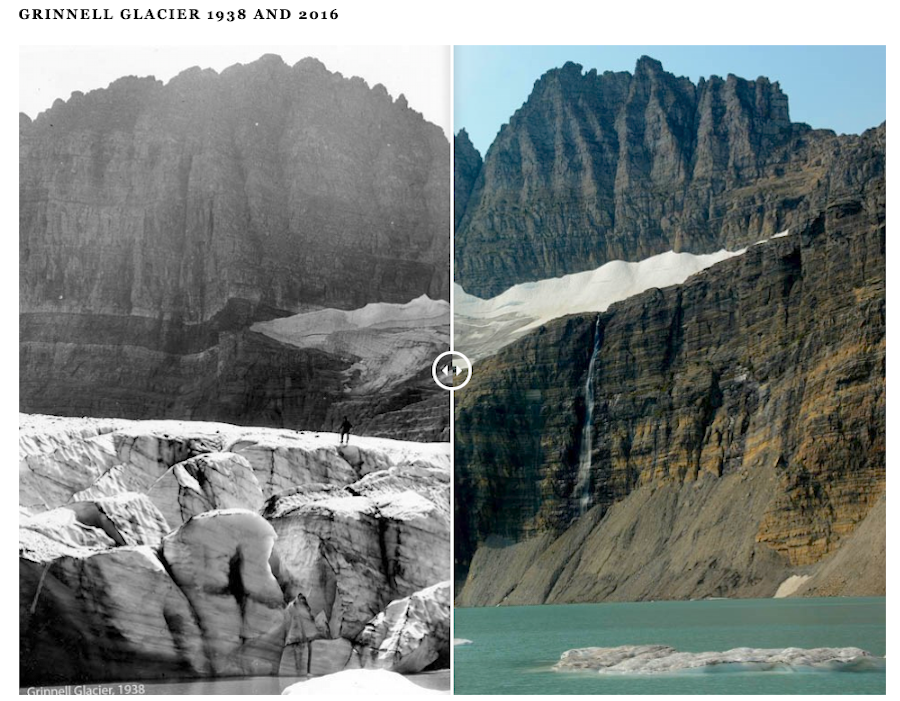

(Left) T. J. Hileman, GNP Archives, 1938; (Right) Dan Fagre, USGS, 2016. The person standing on top of Grinnell Glacier in the 1938 photograph taken by T.J. Hileman gives the viewer a sense of the huge scale. Repeating the historic image today, and including the person for scale, would require a boat/NPS

Park interpretive staff, relying on extrapolations that those two glaciers would be gone by 2020, concluded “the rest of the glaciers in the park would be gone, too. The 2020 date was then put on two exhibits that were erected about 2010 outside the Logan Pass Visitor Center and on two exhibits inside the St. Mary Visitor Center,” noted documents the Traveler obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request.

“Since then (USGS) research has continued and evolved to include a more refined picture of glaciers in the park,” explained Bill Hayden, an interpretive specialist at Glacier, to Lauren Ally, the park’s public affairs officer, in an email. “Like much of scientific research, there are often not concrete black and white answers to basic questions and that is often hard for some people to grapple with.”

When the park staff last spring went into the St. Mary Visitor Center to change the interpretive exhibits, a local resident posted on his blog that that park was "quietly removing and altering signs and government literature which told visitors that the park’s glaciers were all expected to disappear by either 2020 or 2030" after it had previously "boldly proclaimed" that predicton. The post said park officials "seem to be scrambling to hide or replace their previous hysterical claims while avoiding any notice to the public that the claims were inaccurate."

Park officials maintain there was nothing “hysterical” about their interpretive displays.

“There was nothing covert or sneaky about it, but simply an effort to try to have more accurate information in place before the (St. Mary Visitor Center) opened to the public this year,” Jane Ammerman, Glacier’s chief of interpretation and education, wrote Alley in a June 6 email.

“The park’s position (based on scientific evidence) is still that our glaciers are shrinking and disappearing and there is typically a net loss of mass ‘at the end of the year.’ “The prediction that they would be gone by 2020 appears to have been an inaccurate estimate based on the models used at the time, but there is absolutely no disagreement in the scientific community that they will disappear in the not-too-distant future,” she added. “Glacier is removing specific dates and using more general language, as we (and USGS) have realized that although the trend is evident, citing a specific date was perhaps presumptive.”

As those glaciers continue to recede, the landscape will be transformed, whether through altered watersheds or vegetation, and ripple effects from those will course across the park’s ecosystem.

Invasive Species

Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida

Burmese pythons, nearly 1,050 invasive plant species, including Melaluca, and Brazilian Pepper, are among the invaders at Big Cypress. Among the pythons captured and taken out of Big Cypress this year was an 18-foot, 4-inch long female python that weighed nearly 99 pounds and could lay a clutch of up to 100 eggs.

Everglades National Park, Florida

Burmese pythons, Melaluca trees, Nile Monitor lizard, Monk Parakeet, and lionfish are among the invasive species that have taken hold in Everglades. “What concerns me most as a park manager is the invasion of plants and animals that seem to be taking over the landscape, both on land and water," said park Superintendent Pedro Ramos.

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah

Lake Powell has been invaded by quagga mussels, smallmouth bass, carp, and channel catfish, and non-native tamarisk lines some of its shoreline, pushing out native willows and cottonwoods. Though only about the size of a dime, quagga mussels from the other side of the world are impairing beaches, encrusting some boats, and threatening the hydropower operations of the Glen Canyon Dam.

Up Close: Everglades National Park

It was 40 years ago that what very likely was a Burmese python was first spotted in Everglades National Park.

“Verified by Game and Fish Commission,” read the park report from October 24, 1979. “Road kill. Skin at Jim Massey’s. Not an escaped snake from Everglades Safari.”

How the snake slithered into the park is unknown, though it could have been a household pet that grew too big for comfort for an owner who couldn’t bring themselves to just kill the reptile. Soon more pythons were in the ecosystem, and in the ensuing four decades they’ve wreaked havoc on the park’s faunal ecosystem. In a 2012 paper, researchers attributed “severe apparent declines in mammal populations” in Everglades National Park to the constrictors.

Pythons are ravaging small native mammals in Everglades National Park/NPS

“Before 2000, mammals were encountered frequently during nocturnal road surveys within (Everglades National Park),” they noted. “In contrast, road surveys totaling 56,971 (kilometers) from 2003–2011 documented a 99.3 percent decrease in the frequency of raccoon observations, decreases of 98.9 percent and 87.5 percent for opossum and bobcat observations, respectively, and failed to detect rabbits.”

For Ramos, the Park Service superintendent who oversees Everglades and Dry Tortugas national parks, the pythons and other invasive species are changing the very nature of the park.

"I believe that the python is having impairment effects on the landscape down here, not just in Everglades National Park, but beyond," he said.

But pythons aren’t the park’s only invader. There are lizards that go after native species as do the pythons, fish that pose threats to native species as well as coral reefs, and vegetation that while not only competing with native plants and trees but hold the potential for remaking the park's landscape, something that could reverberate through the native species that evolved with, and depend upon, that landscape.

- There are monitor lizards, a reptile from Africa and Asia that can grow to more than 5 feet in length and which preys on birds, amphibians, fish, eggs, and mammals in the park.

- Lionfish, a native to the Indian and Pacific oceans, swim in the park’s marine waters, where they eat more than 70 native fish, some more than half their size. It’s possible, according to the Everglades Cooperative Invasive Species Management Area, that they adversely impact coral reefs by upsetting their ecosystems.

- Melaleuca is a subtropical tree native to Australia, New Guinea, and the Solomon Islands that arrived in South Florida in the early 1900s for, the Park Service says, “swamp drying.” Unfortunately, the tree spreads quickly, pushes out native species such as sawgrass, and is a risk to the park’s marshes, wet prairies, and aquatic sloughs.

Energy Development

Big Cypress National Preserve, Florida

Exploration for, and possible development of, oil reserves beneath Big Cypress adversely impacts the preserve’s landscape, flora and fauna.

The ponderous vibroseis trucks leave miles-long 15-foot wide trails through the park's backcountry, knocking down just about everything in their path and leaving ruts 2 feet deep.

"We have the photos and videos of them cutting (down vegetation). We’re not making this up," said Alison Kelly, a lawyer with the Natural Resources Defense Council. "We have videos of them cutting these trees with chainsaws, or they’re just running them over with the trucks.”

Theodore Roosevelt National Park, North Dakota

Already ringed by pump jacks and flaring stacks, this national park’s Class 1 airshed could be adversely impacted by an oil refinery proposed to be built a small handful of miles from its south entrance. To date, 90 percent of the Little Missouri National Grasslands, which fully surround the park, has already been leased for oil and gas development. This development has brought large infrastructure to the doorstep of the park and the communities nearby. In fact, there are many locations within the park where visitors can see the flares from nearby oil and gas operations. -- National Parks Conservation Association.

Up Close: Big Cypress National Preserve

Imagine the public reaction if trucks weighing 33 tons ground their way across the Hayden Valley in Yellowstone National Park searching for oil. Fortunately, that won’t happen, as there’s no known recoverable oil reserves beneath the valley, and the federal government owns the park’s mineral rights, anyway.

But at Big Cypress in South Florida, there are some oil reserves of unknown quantity beneath the surface of the national preserve, and the Park Service does not own the mineral rights. Instead, they are privately owned, some by Collier Resources Co., which has hired a Texas exploration company, Burnett Oil Co., to send its vibroseis trucks across the preserve to literally pound the ground in a shuddering search for oil.

Videos of the exploration, obtained by NPCA and the Natural Resources Defense Council, not only show the deep ruts the trucks leave in their wake, but also register as the rigs knock down just about everything standing in their way.

As Burnett Oil Co. workers drove the vibroseis trucks, they plow through standing water, leaking hydraulic fluid, and leaving deep ruts in the wetlands, noted NRDC's Kelly. "The company also left trash, debris, and portable toilets behind in standing water.”

Big Cypress embraces a sprawling, humid expanse of subtropical landscape of more than 700,000 acres in Florida's Big Cypress Swamp that contains an amazing, and unusual, assemblage of flora and fauna. There are rare woodpeckers that live in family groups, with youngsters helping to raise their siblings. There's a subspecies of panther (listed as an endangered species nearly five decades ago) that has tenaciously survived despite the steady urbanization of Florida.

More than 30 species of orchids grow in Big Cypress, perhaps most notable among them the Ghost orchid that snakes its roots around the trunk of its host tree, anchoring its beautiful flowers. And there is the Everglades Dwarf Siren, a curious salamander with bushy gills that can grow to 10 inches long. If the exploration work points to valuable oil reserves, Burnett Oil would have to submit a plan of operations for drilling to the National Park Service if it wanted to develop those reserves.

What impact is oil exploration having on the Florida panther?/NPS

"I don’t know why more people aren’t aware that it’s happening, but with the (Florida) panther in particular, it’s such an iconic species. There are fewer than 200 left in the world," said Kelly. "They are literally mowing down its habitat. Literally.

"...I’m just concerned that this is just opening Pandora’s box for the whole Everglades watershed.”

Environmental consultants hired by NRDC this past summer surveyed the area where the vibroseis trucks maneuvered and came away disappointed with soil reclamation efforts.

Quest’s June 2019 inspection of the Preserve revealed that the most basic features of the wetland systems impacted by BOCI’s seismic survey activities have not been restored or mitigated, yet FDEP and NPS, to date, have deemed approximately 90.1% of BOCI’s attempted reclamation as complete. Profound dissimilarities between seismic lines created, and adjacent undisturbed communities remain in terms of ground elevations; dwarf pond cypress cover and density; groundcover abundance, composition, species richness; periphyton cover; and physical soil properties. Recovery of these features does not appear imminent and may not be possible. -- Quest Ecology

Ramos, the Everglades superintendent who once worked in Big Cypress and today remains in touch with projects there, said the work that has been done so far is not the finished product.

"There’s a certain amount of work that we expect them to do after they get done with the exploratory work. They’ve done that work, and we’re actually satisfied with it," he said. "We have to now let some time pass so that we can make observations with respect to how the resource actually responds to the work that they did. Once we can make those observations and really get the story of the level of success of that work, then they will have to do some mitigation.

"I know that some of the environmental community folks have been concerned about the speed of which that initial pass over to do the remediation was done. But from my perspective and from all the reports that I am getting out of the team at Big Cypress, we’re very pleased with the work that they’ve done," he said.

External Impacts

Appalachian National Scenic Trail, Maine to Georgia

Proposals to run energy pipelines through the trail corridor could jeopardize the setting hikers come to enjoy. Earlier this month, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy filed a brief with the U.S. Supreme Court asking that it recognize the Conservancy as having a voice when it comes to protecting the trail from outside development. The case at hand involves a gas pipeline that the U.S. Forest Service had granted an easement for, only to have it blocked on appeal to the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

President Trump’s desire to see a border wall to stop immigrants from reaching the United States is adversely impacting the ecology and archaeology of the monument. "I believe this project could destroy an area with a diverse, multicultural history that challenges today’s border debates," said Jared Orsi, a historian from Colorado State University.

Up Close: Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument

In the early years of the 21st century, the fatal shooting of a Park Service ranger at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument along Arizona’s border with Mexico prompted Congress to appropriate $18 million to build a vehicle barrier along the border in the monument. The murder of Kris Eggle also prompted the Park Service to close roughly 95 percent of the monument to visitors.

That all changed in 2014, when the entire park was reopened after the National Park Service and Border Patrol conceived a plan to allow continued surveillance by the Patrol while Park Service crews erased hundreds of miles of illegal roads and road traces that had been woven through Organ Pipe Cactus.

“We had to reopen the park, because it needed to be open, it’s public land,” Brent Range, the monument’s superintendent at the time, told the Traveler in 2017. “We found no significant reason why it should be closed any longer.”

Kevin Dahl, the Arizona program director for the National Parks Conservation Association, captured the following video in Organ Pipe this fall.

Today's visitors to Organ Pipe have been hindered in their exploration by construction that has been tearing up the park's landscape along the two countries' borders, as the Trump administration has insisted a border wall be erected to stem the flow of Central American immigrants to the United States.

While the wall has proven not to be impervious, its construction has been destructive to the national monument and could impede wildlife migrations, notably of rare Sonoran pronghorns.

A quick field survey by National Park Service archaeologists in June along 11 miles of the borderlands where the wall was to be built identified five archaeological sites. That survey left the archaeologists of the mind that "significant, presently-unrecorded surface-level and buried archaeological deposits persist across the project (are), and we must assume that all such unrecorded deposits will be destroyed over the course of ensuing border wall construction."

“Trump’s promise to build a wall began as a rhetorical flourish during the 2016 presidential campaign,” wrote Jared Orsi, a professor of history at Colorado State University. “But in May 2019, his administration announced that it would waive 41 laws to construct a high barrier. I believe this project could destroy an area with a diverse, multicultural history that challenges today’s border debates.”

Overcrowding

Arches National Park, Utah

Congestion at Arches can be so bad at times that the Utah Highway Patrol closes the entrance road so as not to create traffic problems on U.S. 191. Visitation to the iconic park increased by more than 90 percent in the last 11 years. As a result, visitors face long wait times at the park’s entrance and parking lots. "Waiting hours in line to enter the park or looking for parking are not the memories we want people to take away from their visit to Arches,” said Arches Superintendent Kate Cannon, who retires at year's end.

Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

While the park’s North Rim is relatively crowd free year-round, the South Rim can quickly become congested with visitors for much of the year. You can try to cope with the crowds by parking in Tusayan and riding the park shuttle onto the South Rim, visiting the far-less crowded North Rim, taking the train to the South Rim, or simply detouring to the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park.

Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Shuttle buses have helped ease some of the overcrowding in Rocky Mountain, but the popular Bear Lake Road occasionally is temporarily closed at times during the peak seasons because there are not enough parking spaces for visitors. "We are hearing more and more from visitors who have indicated that they are not coming back to Rocky as a result of the congestion," Rocky Mountain spokeswoman Kyle Patterson said in December 2018.

Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

Frequent visitors say traffic congestion, too many people in general, restroom availability, parking availability, and other visitors acting unsafely around thermal features and wildlife are problems, according to the park’s 2018 Summer Visitor Use Surveys.

Mount Rainier National Park, Washington

With steady flows of visitors from Seattle and Tacoma whenever the sky is blue and "the mountain is out" all heading to the Nisqually Entrance on the park's southwestern corner, the growing crowds are turning what might have been an hour or so drive into a multi-hour slog on summer weekends and holidays. While Seattle is two or more hours' drive from Rainier's Nisqually Entrance on good days, getting through the entrance and up to Paradise at times can turn into four-hour treks. "We see that that’s a problem. We hear about it from visitors that that’s not the experience that they want," said Superintendent Chip Jenkins in late 2018.

Zion National Park, Utah

Crowding has been an issue since at least 2015 at Zion, and park officials in 2017 were considering the use of a reservation system to protect the park’s resources, possibly by limiting visitation to popular areas, such as Angels Landing, the Temple of Sinawava, or Emerald Pools. "We’re looking at those, how we might manage those areas, either on a least common denominator approach, which is more of a park-wide approach, or area by area approach, which has a lot of complexities, but may be able to increase the capacity slightly," said Superintendent Jeff Bradybaugh.

Up Close: Arches and Zion national parks

Nowhere else in the world is there such a collection of stone arches, windows, and fins as at Arches National Park in Utah. So wondrous is this geology that at times it can take the vast number of visitors who come to see Arches hours to pass through the park’s lone entrance just north of Moab.

“Waiting hours in line to enter the park or looking for parking are not the memories we want people to take away from their visit to Arches,” said Arches Superintendent Kate Cannon this past fall when her staff embarked on yet another attempt to come up with a solution to the congestion.

Cannon, who retires at year’s end, thought she had a good solution three years ago, when her staff released a draft plan that called for a reservation system to be implemented during peak visitation months. With a very limited road system, built around the 18-mile-long main road, traffic can quickly slow to a crawl during the spring, summer, and fall seasons at the park's main attractions, such as Delicate Arch, the Windows Section, and Devils Garden.

But that plan ended up being shot down by Interior Department officials, who were concerned by an economic forecast that said such a system could cost the Moab area as much as $22 million in lost economic activity. A similar plan, however, was adopted for Acadia National Park in Maine.

Among the possibilities being kicked around at Arches are a shuttle system, as well as a secondary entrance road, something Utah’s governor has proposed.

Crowds in Zion National Park can adversely impact the visitor experience as well as park resources/NPS

Next spring the park staff will again study traffic patterns to see what tendencies they can glean from the nearly 1.7 million visitors a year who want to marvel at Arches’ arches.

Staff at cross-state Zion National Park long has realized they have an overcrowding problem on their hands. Crowd control alternatives under consideration at Zion include limiting the daily number of visitors to popular areas, such as Angels Landing, the Temple of Sinawava, or Emerald Pools. Another possibility would be to institute a reservation system for visitors to the entire park.

Complicating the planning process are concerns over how a visitation cap would impact area businesses.

“I think people realize that there are crowding problems, and would like to see some solutions to that," Superintendent Bradybaugh told the Traveler a year ago. "But there’s a great amount of concern that that could have negative economic impacts on the tourism industry. And we certainly are taking that into account and have those concerns as well."

Sea Level Rise and Storm Surge

Surf washing ashore can be a pleasing rite of summer as it splashes over your feet, but when the surf reaches farther and farther up that shore, it becomes a problem that impacts both recreation and natural resources.

According to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, that surf is reaching farther ashore in some places than others. For example, “Over the 20th century, sea level has risen about a foot and a half in coastal communities near Cape Hatteras in North Carolina and along the Chesapeake Bay in Virginia,” the organization says.

Impacts range from overwash that rips up roads and other infrastructure, erosion that can transform beaches and force the relocation of lighthouses, and the loss of land turned into marshes.

Cape Cod National Seashore, Massachusetts

The seashore’s outer beaches are eroding faster than ever, and habitat for birds and other organisms are being impacted.

Fire Island National Seashore, New York

Not only did a 2012 hurricane cut a breach through the national seashore, but flooding frequently intrudes on park headquarters.

Assateague Island National Seashore, Virginia/Maryland

Park staff has developed novel ways to protect seashore facilities from storm surges. Earlier this year they also developed a "flexible design strategy for relocating campsites at its Oceanside Campground" to the west to protect the campground from coastal storms.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore, North Carolina

Hurricanes more frequently damage North Carolina 12, the only highway that accesses the national seashore. "Highway 12 on Ocracoke near Southdock is badly damaged along two 500-foot sections, rendering the road unusable," Cape Hatteras Superintendent David Hallac said in September after Hurricane Dorian plowed through the Outer Banks. "I watched waves break over the crumpled asphalt during the high tide."

Cape Lookout National Seashore, North Carolina

As Hurricane Dorian in September 2019 demonstrated, Cape Lookout is increasingly vulnerable to storms that can breach its barrier islands, uproot utility lines, and damage facilities. "It’s an incredible event, 54 inlets at once. It’s just amazing. And scientists that have been looking at the area, I can’t imagine what they’re thinking," said Cape Lookout Chief of Interpretation and Education B.G. Horvat after Dorian. "You see a lot of tipping points for climate change around the world, and this seems to be something similar to that."

Fort Pulaski National Monument, Georgia

Park staff in December still were cleaning up after Hurricane Dorian, with trails along the dike system and in the historic area of the park have been closed for public safety.

Up Close: Cape Lookout National Seashore

As far as hurricanes go, Dorian didn’t seem to merit much more than a sigh from hurricane watchers. As it approached the Outer Banks of North Carolina this past September, it was rated a Category 1 storm, the weakest category on the hurricane rating system.

But what Dorian left in her wake spoke otherwise. When Hurricane Sandy, it too a Category 1 storm, arrived on the East Coast in the fall of 2012 it carved an Atlantic Ocean-to-Great South Bay breach through Fire Island National Seashore. That was impressive at the time, but Dorian’s wrath at Cape Lookout far surpassed Sandy at Fire Island. While Cape Lookout’s three barrier islands -- North Core Banks, South Core Banks, and Shackleford Banks -- stretch 56 miles, Dorian carved more than 50 breaches into those islands, or roughly one every mile.

“Dorian was not a monster storm. This was a Category 1 hurricane going by offshore," said Robert Young, director of Western Carolina University's Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines.

"The way the winds were circulating produced an unusually large storm surge on Cape Lookout for a Category 1 storm,” he added. “The 'end message' is that places like Cape Lookout, with the combination of repeated storm impacts and rising sea level, are becoming more and more exposed, or susceptible to even a Category 1 or 2 hurricane like Dorian.”

In mid-December, the aftermath of Dorian was still evident.

"Most of the breaches have all filled in, though the dune line remains flattened in the areas where the breaches have filled," Chief Horvat reported. "At present, North Core Island is drivable as far south as Old Drum Inlet (Mile Marker 19) and as far north as Mile Marker 6, a distance of about 13 miles. Of course, this time of year, the vehicle ferry is closed through late winter/early spring. So visitors trying to get to North Core will need their own boat transport to even get there, much less get a vehicle over there.

"Mile Marker 6, and north of that, at Mile Marker 2, the breaches there seem to be deeper and flowing pretty well, as of late. It remains to be seen what will happen there over time," he went on. "Of course, as a visitor may be concerned, there are no amenities (water, fuel, ice, bath house, restrooms, dump station), and camping is not allowed in the Long Point Cabin Camp. The cabins are still closed with lots of work to be done in getting those up and running again, and the future is still in a holding pattern as to how to proceed there and at historic Portsmouth Village (located at the northern tip of North Core island, and north of MM 6 & 2).

The likelihood of even more potent hurricanes ravaging the Outer Banks in the years ahead raises questions for what Park Service managers can do to protect Capes Lookout and Hatteras from even greater damage, and where they'll find the money to repair what damage is inflicted on their parks.

Threatened National Parks

Impacts from sources beyond their borders, overcrowding during some parts of the year, air quality issues, invasive species, and even the maintenance backlog in the National Park System all pose threats of varying degrees to some parks.

Air Quality

Automobile exhaust, methane spewed from energy development, smokestack emissions, and even dust stirred up from traffic can combine into a choking, unhealthy air mass that adversely impacts not only human visitors but native flora and fisheries in parks.

Dinosaur National Monument, Utah-Colorado

Energy development in Utah’s Uintah Basin creates air quality issues for Dinosaur, where the ozone levels at times exceed national standards for health. Utah’s governor even implored the U.S. Bureau of Land Management not to permit energy exploration close to the monument to preserve the views.

Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado

Heightened nitrogen loads from air pollution adversely impact vegetation in the park’s high country. “Long-term research in Rocky Mountain National Park has found that, over time, increasing nitrogen deposition has caused changes in soils, alpine tundra plant communities, spruce forests, and alpine lakes,” the Park Service notes.

Sequoia National Park/Kings Canyon National Park, California

Air quality in these two national parks is adversely impacted by air pollution coming in from California’s Central Valley. “In 2018, four parks--Sequoia, Kings Canyon and Joshua Tree National Parks and Mojave National Preserve—had unhealthy air for most park visitors and rangers to breathe for more than two months of the year, mostly in the summer months,” said the National Parks Conservation Association.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park, North Carolina/Tennessee

Though improvements are being recognized, high ozone levels and visibility problems still impact the park, particularly during summer, and the park’s trout fisheries are threatened by stream acidification related to air pollution.

External Threats

Human development – urban sprawl, road infrastructure, commercial ventures – all are impacting parks even while they occur beyond park boundaries. Legal efforts can try to stop some of these threats, but they are costly and can take years to succeed.

Biscayne National Park, Florida

Efforts to restore and protect a stretch of the only tropical coral reef system in the continental United States date to the 1990s, at least, but Biscayne’s efforts have been derailed by politics. While environmental organizations have called on Florida, which manages the fisheries in park waters, to institute no-take regulations, the Fish and Wildlife Commission in December adopted draft rules to simply limit some of the takes.

Cumberland Island National Seashore, Georgia

A spaceport proposed to be located less than 5 miles west of Cumberland Island could one day launch rockets directly over the national seashore and its wilderness area. “We have nothing against rocket ships unless they’re being launched over one of the largest maritime wildernesses on the East Coast,” said Emily Jones, who works in National Parks Conservation Association’s Southeast office. “A place where people go for peace and quiet, solitude, and a place that has a huge number of historic properties, some of which are somewhat fragile that will be impacted by sound repercussions.”

Colonial National Historical Park and Historic Jamestowne, Virginia

A power transmission line more than seven miles long runs through the James River and creates a visual impact on Colonial, Historic Jamestowne, and even the Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail. Legal battles today should determine whether Dominion Virginia Power wrongly was allowed to install the towers and whether it now needs to remove them.

Invasive Species

Haleakalā National Park, Hawaii

Haleakalā National Park has more threatened and endangered species than any other park. In a bid to slow the invasion, Congressman Ed Case and Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard just this past Thursday introduced a bill to require that all baggage and cargo transporting into the State of Hawai’i by air or sea be inspected for invasive species and high-risk agricultural materials. “We must act now because invasive species pose an especially grave and accelerating threat to Hawai’i ,” said Rep. Case. “Isolated Hawai’i has one of the highest numbers and rate of endemic species anywhere and invasive species have wreaked havoc on our natural environment.

Big Thicket National Preserve, Texas

Wild hog populations in the preserve have grown to the point where park staff implemented both a public hunting season and professional trapping to blunt the population growth. In 2018, professional trappers removed more than 1,200 hogs from the preserve. In 2019, those two efforts were aided by implementation of a public trapping program.

Maintenance Backlog

Insufficient funding, reduced staffing, and storms and visitation that create new maintenance problems make this issue a perpetual problem that the National Park Service just can’t get ahead of. Though George W. Bush as a presidential candidate said he would erase the $5 billion maintenance backlog that existed during his first campaign within five years, he never came close. While Park Service managers can draw up plans and offer proposals for tackling their backlogs, without sufficient funding from Congress the problem grows year after year.

Blue Ridge Parkway

Bluffs Lodge at milepost 241.1 on the Parkway closed at the end of the 2010 season, its 24 rooms deemed unprofitable by the concessionaire. Since then, the buildings have been closed to business and invaded by mold and decay. Though the Park Service has put new roofs on the buildings, the interiors remain unhealthy and uninhabitable.

Grand Canyon National Park, Arizona

Ongoing issues with the nearly six-decade-old pipeline that brings water from the North Rim of the park to the South Rim have led to the recurring need for water conservation measures on the South Rim, which sees roughly 6 million visitors a year. Park staff has a plan to replace the pipeline, but it’ll cost roughly $100 million and won’t be in place until 2025 at least.

Traveler postscript: Be sure to download Traveler Podcast Episode 45 to listen to Kurt Repanshek's interview with Mark Wenzler of the National Parks Conservation Association and Phil Francis of the Coalition to Protect America's National Parks.

National Parks Traveler, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit media organization, depends on reader and listener support to produce stories such as this one and other coverage of national parks and protected areas. Please donate today to ensure this coverage continues.

A copy of National Parks Traveler's financial statements may be obtained by sending a stamped, self-addressed envelope to: National Parks Traveler, P.O. Box 980452, Park City, Utah 84098. National Parks Traveler was formed in the state of Utah for the purpose of informing and educating about national parks and protected areas.

Residents of the following states may obtain a copy of our financial and additional information as stated below:

- Florida: A COPY OF THE OFFICIAL REGISTRATION AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR NATIONAL PARKS TRAVELER, (REGISTRATION NO. CH 51659), MAY BE OBTAINED FROM THE DIVISION OF CONSUMER SERVICES BY CALLING 800-435-7352 OR VISITING THEIR WEBSITE. REGISTRATION DOES NOT IMPLY ENDORSEMENT, APPROVAL, OR RECOMMENDATION BY THE STATE.

- Georgia: A full and fair description of the programs and financial statement summary of National Parks Traveler is available upon request at the office and phone number indicated above.

- Maryland: Documents and information submitted under the Maryland Solicitations Act are also available, for the cost of postage and copies, from the Secretary of State, State House, Annapolis, MD 21401 (410-974-5534).

- North Carolina: Financial information about this organization and a copy of its license are available from the State Solicitation Licensing Branch at 888-830-4989 or 919-807-2214. The license is not an endorsement by the State.

- Pennsylvania: The official registration and financial information of National Parks Traveler may be obtained from the Pennsylvania Department of State by calling 800-732-0999. Registration does not imply endorsement.

- Virginia: Financial statements are available from the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, 102 Governor Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219.

- Washington: National Parks Traveler is registered with Washington State’s Charities Program as required by law and additional information is available by calling 800-332-4483 or visiting www.sos.wa.gov/charities, or on file at Charities Division, Office of the Secretary of State, State of Washington, Olympia, WA 98504.

Comments

The problem is overpopulation. There are too many people using the parks and living near the parks.

I agree. There are too many people - period. Overpopulation is a fundamental problem. Imagine what Earth would be like with a human population of 4 billion, that population being distributed in the same ratio between countries as is the current 7-8 billion. Imagine what the USA would be like with a population of 150 million. Impossible? Well if the ecosphere collapses, maybe not. Where is Bertrand Zobrist when we need him?