The Cactus Forest at Saguaro National Monument in 1935/NPS

Take saguaros out of Saguaro National Park, and you’d lose more than the park’s namesake cactus, one that gives skyward structure to the vista here.

You might be left straining to catch the drumming of the Gila woodpecker, fail to catch an elf owl peering out from its cavity nest, and not know where to look for Lesser long-nosed bats. All these creatures rely on the saguaro for food and/or shelter.

Realizing those possible losses to this Sonoran Desert landscape begs the question, "How are the park’s saguaros doing?"

To try to answer that question, I headed to Tucson, Arizona, and the national park. The last time I visited Saguaro it was spring, the desert was a figurative riot of color. There were ocotillo, their orange-flowered tips glowing like fireplace pokers, and violet-bloomed Hedgehogs, patches of pink Fairy Dusters, bluish-petaled Scorpionweed, and a hillside studded with sagaruos and painted in yellow brittlebrush.

In early November, most of the color was gone, but the saguaros stood stately as usual.

At the parking lot of Saguaro's Rincon Mountain District I met Don Swann, a wildlife biologist and saguaro expert who has written or contributed to numerous papers pertaining to saguaros and other aspects of the Sonoran Desert. My timing was great, as Swann was heading into his once-a-decade saguaro census in the park.

“I think there are many answers to why we conduct the census,” he said as we walked through the entrance gate and into the park. Overhead, the sky was a cloudless blue, and already at 9 a.m. the temperature had reached 80 degrees.

“But the most basic is we feel it is our responsibility to keep track in a scientific way of the saguaro population in the park. 'Saguaro' is the name of the park, it’s the reason we’re here. It’s obviously a real important plant for the Southwestern deserts and southern Arizona,” the ranger said.

The Cactus Forest at Saguaro National Monument in 1960/NPS

The decadal surveys, which date to 1990, allow park managers to see how the saguaro population is changing across the park’s two districts.

“We’ve been able to really use that information in the last few years to see that there are differences in different parts of the park, in different habitats,” Swann explained as we walked along. “National parks are reference areas for other areas that may be damaged by things that we humans do, and so, this allows us to see how well the saguaro is doing in an area that’s being managed for natural resources.”

Saguaro cacti are fascinating plants, iconic entities that not only benefit many creatures that call the desert home, but are reliable and picturesque backdrops for more than a few cinematographic Westerns. They are tall and silent, but hardly unnoticeable.

“Saguaro is a fascinating plant for us as humans for a lot of reasons. It’s very charismatic. It’s a charismatic mega-plant, really,” Swann told me. “Some people would call it a keystone species because so many animals depend on it. That runs the gamut from the small insects that pollenate the flowers all the way to javelinas and other mammals that depend on the fruit to eat.

“The saguaro is providing food in the form of nectar in the flowers. They have these beautiful white flowers that bloom at night,” he continued. “The fruits themselves are very rich in calories and other things that are really good for animals. They provide shelter. We have elf owls, for example, that nest in holes that are constructed in saguaros by woodpeckers. The holes are constructed and the nest is built inside, then the holes can be reused by other birds in future years.”

Don Swann, Saguaro National Park/NPS

Great horned owls and Harris’s hawks will build their nests on the outstretched arms of saguaros, while the Gila woodpecker and Gilded flicker will carve out cavities that they use for one nesting season before abandoning them to other species.

“Even when they die,” adds Swann, “as the flesh is rotting, its full of these amazing insects that live in the rotting saguaro. And then the wood, what we call the saguaro ribs, lay on the desert floor for many years and provide habitat for lizards and birds even. And so it’s really contributing to the wildlife population throughout its life cycle.”

As we roamed the park landscape, it was easy to spot saguaros that, surprisingly, were quite old. These cacti don’t grow quickly. A quarter-inch tall version might already be two years old, a desert sprite overlooked amid other vegetation. That’s why it can be difficult to gauge just how many saguaros are in the park, despite the census every ten years. There are 45 plots in the park that are part of the census, and each covers about 400 hectares, or almost 1,000 acres.

For the census, volunteers from school groups, hiking clubs, businesses, University of Arizona fraternities and sororities, join park biologists and head for the 45 plots.

"We bring them out, we kind of teach them how to measure the saguaros, how to collect the data so that it’s accurate, how to search for the saguaros," explained the biologist. "We break into small groups and we do that. We check each other’s work, so we double search each area. And then we try to finish that plot with the group. But if there’s 1,800 saguaros and it’s a long hike to the plot, because they’re randomly located, it might take us four or five different groups to finish a plot. So it’s usually done on a Saturday. We also try to get as many weekday groups as possible, and we just keep chipping away at it with the goal of finishing all 45 plots by April.”

Walking along, Swann leads me over to what turns out to be a somewhat young saguaro.

“So we systematically work our way through the plot. And then when we find a saguaro, we stop, and we measure it," the biologist said as he unfolded his measuring stick. “So something like this, this stick is about 180 centimeters, so about 6 feet tall. So what I’ll do is, in this case I can measure this just by hand, so I’ll put my finger right here, at 180 and have you tell me, including the spines when I’m at the top."

While the biologist is wielding his measuring stick, he explains that since 1941 Park Service biologists have been measuring saguaros and so have been able to come up with an average annual growth rate and then attach an age to individual cactuses, depending on how tall they are.

“We have a really good kind of average growth rate for saguaros in this district of the park," Swann said. "It’s slightly higher than the average growth rate of saguaros in the west district of the park, which doesn’t get as much rain. And during rainy years they grow faster, and during dry years they grow slower. But I can say, on average, this saguaro would be about 38 years old.”

Once upon a time, back in the 1930s when the park was established as a national monument, the area known then, and now, as the Cactus Forest was thick with saguaros reaching into the sky. But over the decades the forest thinned out, dramatically when you look at photos spanning the decades.

The Cactus Forest, 1985, Saguaro National Monument/NPS

But, I learn as Swann leads me around in search of saguaros of different ages, that diminished panorama is not evidence of a staggering downfall of this desert icon.

“That’s a great question,” he replies when I ask if we'll see those dense saguaro forests one day return, “and the answer is no, I don’t think we will. But not for the reasons most people think.

“I think those saguaros that we have out there today will grow up and they’ll get arms and they’ll be impressive, but part of what makes that photograph so impressive is that there aren’t trees, and so that you can really see the saguaros,” he said. “So in order to get back to that same scene we’d probably have to cut down the trees again, which we’re not going to do.”

As we walk, the effort to appreciate how old an individual saguaro is is an ongoing challenge. Coming upon a group of three, Swann asks how tall I think one is. After I guess it’s about 20 feet tall, the biologist tells me that corresponds to nearly 70 years in age.

Not 10 yards away Swann spies a much, much smaller one, roughly a foot tall.

“So this one is certainly tall enough to be able to store water and be pretty resilient to a drought situation. But, it’s older than most people would think,” he said, bending down with his measuring stick. “Let’s see, it’s about about 48 centimeters (18 inches), which makes it about 21 years old.”

Looking around at various saguaros, I ask the biologist at what age saguaros sprout their "arms," or branches.

“They don’t always appear. You don’t always get arms on saguaros. I always like to ask people, so I’ll ask you: Why do you think saguaros have arms?," he said.

“For bird perches," I offer, sending us both into laughter.

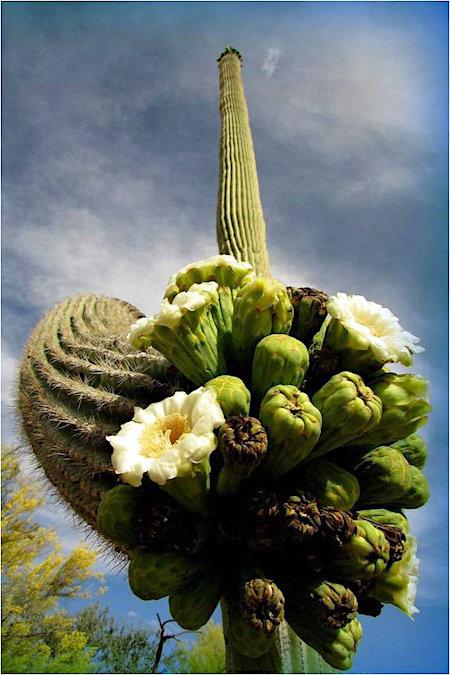

Saguaro in bloom, Saguaro National Park/NPS

"The answer is that they produce the flowers at the tip of the growing stems, and they can produce flowers at the end of every arm as well. So a saguaro that’s doing really well, is getting enough water for survival, is then beginning to put its energy into reproduction," explained Swann. "So once they reach a certain age or a certain size, and it’s usually not until they’re older than I am, they will start to put out arms if they’re in a favorable place, and then they can put out multiple arms.

“If you look around here, you can see some small arms that are just starting, some big arms that have been there for a long time. So they can put out those arms and they can basically produce more flowers, more fruit, and more seeds. And so they’re getting their seeds out on the landscape in larger numbers because of those arms.”

Those uninitiated to the Sonoran Desert and saguaro biology likely wouldn’t notice, or not think it unusual, that these smaller saguaros are growing up next to trees or bushes. These trees -– mesquites, palo-verde, acacia -– are called “nurse” trees for the benefits they bring young saguaros until they’re old enough to make it on their own. They provide shelter from the hot sun in summer and even from the cold of winter.

Swann tells me that research is under way to try to determine if one particular species is a better nurse tree than another.

“Scientists have long suspected that one of the critical factors for young saguaros is protection from the cold during these freeze events that we occasionally get,” he said. “There’s also potentially a moisture benefit. The nurse trees provide, just from the shade itself, greater moisture underneath the tree, but there’s a fascinating line of research being pursued by one of our collaborators who’s looking at nurse trees, like palo-verdes and mesquites, bring up water through a process called hydraulic lift from ground water that’s deeper in the ground.

“There’s some evidence that their roots at the surface leak a little bit, and that little bit of lost water potentially could be taken up by saguaros and help their survival,” said the park biologist. “So it may be that the nurse trees are benefiting the saguaros through this kind of water transfer.”

Sometimes, rocks provide the “nursing” by shielding young saguaros from the sun and providing a measure of radiated warmth in winter.

Gazing around at the Cactus Forest landscape, and recalling those photos from the 1930s and ‘40s, my mind wanders to the bottom line of the census.

“People hear the word ‘census,’ and they might imagine that you’re coming up with a finite number of how many saguaros you have in the park,” I said.

“The word is inaccurate, it is not a census,” replies Swann with a grin. “We are not counting every saguaro in the park. However, we use the number from the plots to estimate how many we have in the park. And we estimate, based on the 2010 census, that we have about 1.9 million saguaros in the park.”

“And how does that relate to the first census back in 1990?” I ask.

“It’s increased dramatically. I don’t have the exact numbers, it’s not quite doubled, but it’s increased significantly since 1990,” is the answer.

The reason the landscape doesn’t seem to hold that many is that young saguaro can be hard to spot to the untrained eye.

“In 1990 they didn’t find a lot of the very young saguaros that were not visible yet,” the biologist explained. “They were there, but we didn’t find them. But yeah, there’s been a tremendous increase in the number of saguaros in the park in the last four decades.”

As we head back to the visitor center, Swann reminds me of the mission of the National Park Service.

“In national parks, our job is to protect resource, like saguaros, for future generations,” he said. “It’s not just about us, it’s about will people be able to come here 30 or 100 years from now and see a saguaro, and what can we do, how can we gain knowledge that will allow us to make good decisions to protect the desert and protect the saguaro.”

Cactus Forest, 2010, Saguaro National Park/NPS

Traveler footnote: Catch Traveler's entire interview with Don Swann in our podcast, National Parks Traveler Episode #40.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Comments

Kurt, If you are still in Tucson, don't miss the nearby Desert Museum. And drop me a note, I'll buy you an adult beverage.

Did you know that there's a saguaro (ceramic) forest at the entrance to the Cairo (Egypt) International Airport?

That's a classic old logging industry trick: cut down the old growth trees, plant lots of new seedlings, count the number of trees and watch the size of the forest grow.

Quality is lacking, but quantity is booming!

Too bad we don't have good estimates of the numbers before 1990, I think there is more to the story...

It would be interesting to see an analysis of the photos. Certainly wouldn't capture the young cohorts - but it would be a compelling comparison.

For additional background (co-authored by Don Swann), have a look at: A History of Saguaro Cactus Monitoring in

Saguaro National Park, 1939-2007 (at http://npshistory.com/publications/sagu/nrr-2009-093.pdf).

Wilbur: you're certainly right about some commercial foresters claiming 10x as many trees on their land because each large tree they cut gets replaced by hundreds of seedlings and dozens of saplings. But saguaro, not so much.

Good estimates for a few other plots date back at least to Forrest Shreve's plot on Tumamoc Hill established in 1909: see the report RD linked to above, and Joe McAuliffe's 1993 history noting the several times top managers thought the saguaro were disappearing https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/DownloadFile/152763 Pierson & Turner 1998 reports on 85 years of dynamics on the 1909 Shreve plots, but doesn't have a free copy online. The 1990 plots are a much larger set, and are randomly-located, so help tease out site-specific artifacts from long-term dynamics.

Desert plants are different. Short term trends, even over decades, don't predict long-term trends. Think sawteeth for densities over time. Some species gradually increse in number in most years, but crash way down in occasional years. Other species have modest mortality and no recruitment of new individuals in most years, but rare bursts of successful germination and establishment.

Something that happens only once or twice a century like creosote seedling surviving the first year or sand verbena producing 100k -250k seeds per plant would require millenia of data to get good estimates on that frequency or estimates on just how many seedlings survive or seeds are produced. Saguaros aren't quite so extreme, as the 100+ years of demographic data and varying size distributions suggest that new plants establish every couple of decades.

So, what the heck does this all mean? It means that even with 20-50 years of careful annual data, the trend you see in numbers tells you little of the long term dynamics driven by rare events. Forrest Shreve, Ray Turner, Joe McAuliffe, Elizabeth Pierson, Janice Bowers, and other scientists have done clever work and established plots for the long-term or picked up the torch as others retired. Don Swann continues that as both a scientist and a manager.

Oh come on! Is everybody kidding and I just don't get the joke? I look at the photos, seemingly all taken from roughly the same perspective. I look at 1935, then 1960, and I see a difference, but still have doubts. Then I look at 1935, then 1960, then 1985, and I don't have any doubts at all; something is definitely wrong. When I add the 1985 photo, it's a disaster and what's worse is that pretty much everyone seems okay with it. Yellowstone in 1989 is running through my mind, only there wasn't any stand replacement fire here. When I read the article, Ranger Swann, who's supposed to be the "saguaro expert" and billed as having "written or contributed to numerous papers" on saguaros, seems focused on his status as the cactus counter, with local outreach, and with teaching the little folks how to help with his census; but, he doesn't seem to be raising too much of a ruckus about what his own agency's photos show is happening to the species that is supposed to be at the core of his expertise.

From what I read in the article, he knows that the older specimens are the only ones putting out arms and that the arms are the seed producing mechanisms, essential to reproduction of the species; but, is he, as a biologist, concerned with the clearly visible loss of such a high proportion of the older specimens? Yes, we all know or should know about the importance of nursery plants and nursery rocks and I'm glad that there are so many immature saguaros out there; but, all that begs the very critical question of what has been happening to the mature specimens since 1935. What factor or factors caused such a significant thinning of the stand seen in these photos? Did the mature specimens seen in the 1935 photo simply all reach a lifespan limit over the years, like a lodgepole forest reaching the critical mass for a stand replacement fire, or does a saguaro forest exhibit such a lifespan effect? Has the effect occurred at a constant rate since 1935 or has it been accelerating or decelerating? Is it continuing or does it show signs of stopping? Is it a natural stand replacement phenomenon that takes older specimens, while leaving younger saguaros to grow, or is it, in a worst case scenario, some factor that is or will be attacking younger plants before they will be able to reach reproductive maturity.

Look, I'm glad that, as Ranger Swan points out, there's been "a tremendous increase in the number of saguaros" in the park. But, as he also points out, his "job is to protect resource, like saguaros, for future generations" and, although his census information is part of that process, I'm not reading where he is fully acknowledging or articulating what is happening to the resource or saying anything about what might have caused it, is causing it, or what. if any, research is being aimed at determining any of that. And, I'm not seeing anybody getting too worked up about it.

I'm not reading where he is fully acknowledging or articulating what is happening to the resource or saying anything about what might have caused it

Perhaps because of the article's length, the question about what might have caused it wasn't included... or maybe wasn't asked. As a volunteer at SAGU, I'll take a crack at it. A major factor in the population's decline was... SURPRISE... human-related. Due to old leases that were inexplicably extended, cattle grazing was allowed in Saguaro National Monument until the late 1970s (it existed only in the eastern district as the western wasn't suitable) and it goes without saying that livestock trampling around for decades in the Cactus Forest wasn't good for reproduction. More human involvement... Lime kilns were operated for about thirty years in what later became Saguaro NM & all trees in the Cactus Forest were cut down to keep them fired... that's why practically none are visible in the 1930s photos. No trees, no protection for young saguaros. Mother Nature was also involved, with some unusually cold winters in the 1930s and 40s resulting in some saguaro loss. Those are reasons for the decline in saguaro population of which I'm aware.

https://www.nps.gov/articles/history-of-saguaro-cactus-monitoring.htm