The rain has been doing its magic in Southern California. Green has returned to the fire-blackened Santa Monica Mountains, fresh growth emerging from the ash of the biggest fire ever to sweep the 154,000-acre park that’s hemmed by the Pacific’s white beaches and the sprawl of greater Los Angeles. Tiny seedlings dot many slopes, looking in the distance like a green peach fuzz, and brilliant lime grasses, invasive as well as native, stretch beneath craggy mountains that still wear the charcoal face left by November’s ferocious Woolsey Fire. The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area is on the mend, with months and years of fire-recovery work ahead. But not everything under National Park Service stewardship is easily repaired, and some losses are forever.

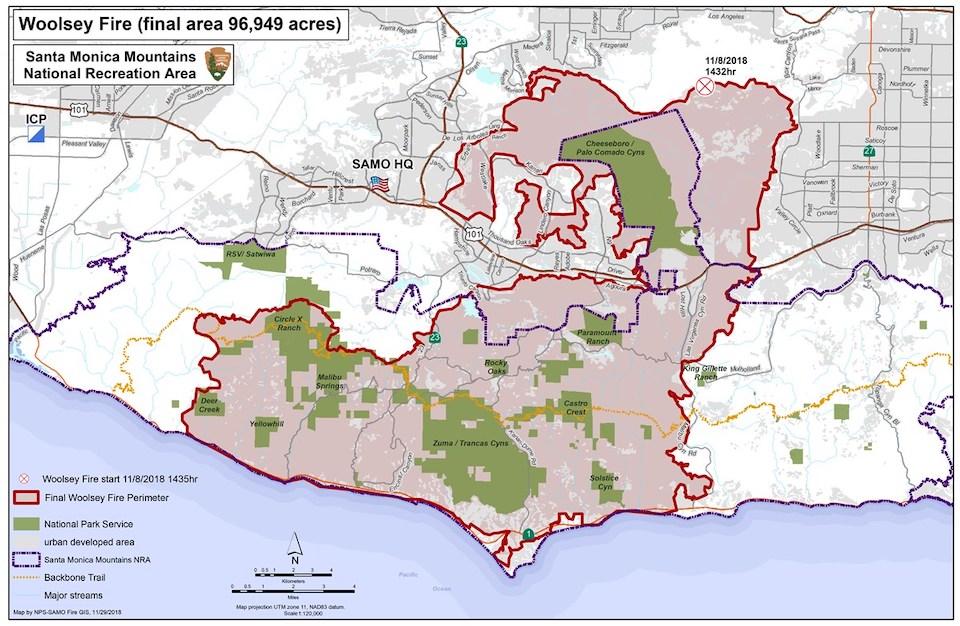

The Woolsey fire in the fall of 2018 swept over nearly 90 percent of National Park Service land in Santa Monica Mountains NRA/Rita Beamish

SANTA MONICA MOUNTAINS NATIONAL RECREATION AREA – Ann Stansell poked at a file-storage box containing what used to be a two-foot-long metate, a curved rock slab used with a pestle to grind acorns and seeds, a vital tool of Native American life in this coastal region.

Now the mortar inhabits three boxes on a storeroom shelf, reduced to blackened, irregular chunks ranging roughly in size from a piece of toast to a book. Burned, but not burned up -- the fire didn’t pulverize granite.

“It’s not like you’re looking at an artifact. Now you’re looking at pieces,” said Stansell, a National Park Service archaeologist. “We’ll piece it back together.”

That’s not an option, however, for most of the pea-sized rubble in 70-some boxes on shelves lining this small field research station.

Bits of shell, metal, rock and beads, mixed in with fire debris – that’s mainly what’s left of nearly 1 million artifacts in the Park Service’s collection here: tiny pieces of legacy, life, culture and the history of these mountains that rise alongside the urban buzz of the nation’s second-largest city.

The Woolsey fire took the rest when it galloped across 100,000 acres of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in November, showing no mercy to this Rocky Oats area: Maps and historical photographs, including Hollywood on-location shots, film reels, prehistoric fossils and Chumash Indian objects, plant specimens and park historical records -- all now are charcoal crumbs and cinders, melted into a pile of twisted metal that used to be the 1,300-square-foot Museum Research Building that housed the artifacts and archival collection.

Understated, Stansell said, “It’s a big loss for us. What survived is the rocks.”

National Park Service archeologist Ann Stansell surveys the wreckage of the Museum Research Building that housed nearly 1 million historical and cultural documents and artifacts, nearly all of which were destroyed/Rita Beamish

The Woolsey fire, ripping across swanky Malibu as well, devoured nearly 90 percent of Park Service land in the recreation area, a preserve that also includes state parks and other landowners.

Losses included two of 13 mountain lions with tracking collars, and countless smaller wildlife – a recovery specialist described a post-fire moonscape with burned rabbits littering a roadway -- along with oak trees, chaparral and plant life. It ruined wildlife monitoring equipment, trashed uncounted sections of the area’s 450 trail miles, and torched 35 Park Service buildings, some designated as historic. Three employees lost the Park Service homes where they lived. Winter rains on the heels of the fire created more havoc by way of rock and mudslides.

On top of the natural impacts, human transgressions are a headache for law enforcement, said Chief Ranger Trouper Snow. Rangers have been stretched policing hundreds of people who defy trail closures into unsafe areas where culverts are collapsed and rockslides have wrecked trails, and also protecting exposed archaeological and Native American cultural sites that before the fire were hidden by vegetation.

Metal handcuffs and memorabilia that survived the Woolsey fire/Rita Beamish

And, said Snow, “Resource protection from off-roading is definitely the biggest challenge right now.” Off-roaders wreck nascent plant growth and scar the landscape that is newly accessible due to fire. To help patrol, two additional law-enforcement rangers are coming onboard, and cameras will help monitor some sites.

One scofflaw faces a court date after getting his vehicle half buried in mud. The park is trying to figure out how to extract it from an isolated region without further damaging the land with equipment. In any event, said Snow, the driver will have to pay dearly for removal and restoration.

Where The West Was Fun

The extent of damage created “a grieving process” of sorts for park workers in the Woolsey fire’s aftermath, said park Superintendent David Szymanski. But optimism returned with the rains. The focus is on digging out and building back.

Prominently, the fire flattened a major park resource, the active Western movie set at Paramount Ranch, the only Park Service site to tell the story of American filmmaking. Gone are the Old West saloon, sheriff’s office and hitching posts featured in TV shows and movies such as West World, Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman, The Lake House, and The Cisco Kid. The ranch drew 370,000 visitors a year, including to arts and music festivals, but Western Town now is just crumpled metal and rubble behind chain link fencing, awaiting removal of hazardous materials and a rebuilding plan.

“We’re focusing attention there to get it rebuilt,” said Szymanski, who’s enlisted the nonprofit Santa Monica Mountains Foundation to raise $1 million for new set buildings. Beyond that, the ranch will account for a large chunk of the $29 million that the park estimates it needs to rebuild its structures overall, ranging from crisped trail bridges to the Peter Strauss ranch house, site of weddings, concerts, community programs like the one that brings 20,000 Los Angeles school children to the park, he said.

Paramount Ranch set at Santa Monica Mountains NRA/NPS

Burned remains of Paramount Ranch following Woolsey Fire/Rita Beamish

Immediate Needs

Emergency stabilization money for the most immediate safety and resource needs – as opposed to longer term rebuilding and conservation – has been approved at nearly $1.4 million, following evaluation by specialists from the Burned Area Emergency Response Plan (BAER), a National Park Service process involving a multi-agency assessment team.

Longer term costs and the ecosystem toll are being calculated across the park’s landscape of chaparral, riparian woodlands, and delicate coastal sage scrub that is the region’s only home to the California gnatcatcher, a threatened bird.

Burned Or Killed?

Fire burned nearly 44 percent of chaparral, nearly a third of coastal-sage scrub – a species rapidly being lost to Southern California urbanization -- and more than a third of grass and herb lands, including habitat for 22 priority species, the BAER review found.

Importantly, however, “burned” does not necessarily mean killed, said Mark Mendelsohn, a Park Service biologist. Although vast in acreage, the racing fire didn’t burn too deeply into the soil where re-sprouting is nourished – and, after years of drought, the rains have done what no human intervention could accomplish.

“It’s coming back strongly. We’ve had good rains,” said Mendelsohn, out for a recent vegetation survey on a hillside overlooking Paramount Ranch. “This is a great green-up, probably as good as we can expect.”

Vegetative recovery can be seen in parts of the NRA, though native plants could be mixed with invasives/Rita Beamish

Park Service biologist mark Mendelsohn and his team conduct a post-fire vegetation survey, counting plants, describing species for comparison to last year’s vegetation in a series of specific transects. They pound white plastic poles into the ground to mark the transect and replace poles that were melted by the Woolsey fire/Rita Beamish

Mendelsohn and four team members painstakingly recorded the diversity of green sprouts emerging from damp, ashy soil where tall skeletons of burnt chaparral pointed skyward like crooked fingers in the midday glare.

Spotting a rust-colored bit of plant life, a shrub oak, Mendelsohn proclaimed, “That’s great news. It’s re-sprouting.” The team pounded white plastic poles into the earth where fire had melted old ones, to mark transects for future recounts.

“A year ago, we would be crawling in here,” through a woody chaparral thicket, said Brendan Clarke, a Park Service mapping technician with the group. It’s expected to take more than a decade for shrubs and plants to reach pre-fire coverage.

The fire claimed many oak trees, but little green sprouts are poking out from some blackened trunks. “Whether that tree is ultimately going to make it is a question,” said Park Service plant ecologist John Tiszler, noting that it would be more promising to see new growth up in the branches.

“The years of drought do not bode well for these trees,” as they shoulder built-up stresses, he said. In his first 15 years at the NRA, he saw no trees dying, but in the past five years “we’ve seen lots and lots die” weakened by lack of water and vulnerable to insects, he said. He would not have expected a fire of the Woolsey’s modest intensity to burn the trees so intensively.

“They already were not doing well. We were seeing them dying from drought,” he said. “But the rainfall now does bode well …The question is, is this fire the final blow for the trees, or just the latest insult?”

Loss of the native oaks, said Szymanski, is “a big worry, a huge issue.”

Also problematic are invasive weeds, on the march and the biggest threat to native species recovery. They grow fast, burn easily and spread quickly after fires to crowd out native plants, increasing future fire vulnerability. Twenty-five area species are considered “highly invasive and ecologically damaging,” according to the BAER report. And research has found that significant acreage of native scrublands already had converted to non-native grasslands before this fire. The Park Service is targeting these weeds in fire recovery, especially around roads, said Szymanski.

Fire Frequency

The other big worry for park officials is the increased frequency of the fires compared to historical patterns, and the question of how long plant life can continue to recover.

The natural cycle is 70 to 100 years between serious fires, said Park Service fire ecologist Marti Witter. Seasonally hot, dry conditions favorable to fires are nothing new here, and vegetation is fairly resilient to fires at intervals of 35 years or so, she said.

But fire intervals have grown far shorter. Significant sections of the NRA had fires between 2 and 18 years apart when mapped in 2012; less than 20 years can cause long-lasting damage to native shrubs, the Park Service says, and less than 12 is red-flag territory for sustainability.

The freeway-jumping Woolsey fire found “massive shrub die back” from drought years along with robust Santa Ana winds to spread the flames, Witter said. But for the Santa Monica Mountains the real fire issue is human activity, Witter and other park experts say. Virtually all the fires are human caused, whether by power tools sparking on a sweltering day, or a car parked over bone-dry vegetation, they say.

Fire frequency is increasing with urban growth, raising questions about the need for more restrictions on red-flag days, and attention to how to clear and vegetate protectively.

For the museum collections at Rocky Oaks, the months to come will entail the “due diligence” of sorting, repairing as possible and cataloguing any salvageable items, with Park Service experts identifying and evaluating scientific value, said Stansell.

As to the broken little bits of what had been meaningful, Stansell said the Chumash have suggested the idea of interring them in appropriate cultural sites, returning history to the earth that saw it live.

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Add comment