Elk at Great Smoky Mountains National Park/NPS

Editor's note: Where can you see, or hear, wildlife in the National Park System in fall? We pulled Danny Bernstein's story out of Traveler's archives to point you in the right direction.

In the fall, animals and birds prepare for winter. Bears eat constantly to fatten up before they slow down. Many birds are already on their migration path. Elk and other ungulates are preparing for the mating ritual, the rut. Take a look -- or stop and listen -- in many national parks this fall and you'll catch a glimpse of this autumnal spectacular.

One of the most hair-raising fall sounds to the uninitiated is that of a bugling bull elk. These bulls summon their harems with both signs of dominance and sounds of ... well, it's hard to describe an elk bugle, as it starts out shrill and tumbles off to a guttural grunt.

Here's a breakdown of where you might go this fall to see, and hear, elk and other wildlife in the National Park System:

There are no elk in Acadia, but the mountains on Mount Desert Island anchored just off the coast of Maine are a great spot to watch migrating birds.

Thousands of birds of prey, including falcons, hawks, ospreys and eagles, migrate through Acadia during the autumn. Each year thousands of park visitors join Hawk Watch to see and learn more about these fascinating birds.

From now through late October, weather permitting, park rangers and volunteers working with staff from the Schoodic Institute atop Cadillac Mountain will help visitors find and identify birds passing by and provide natural history information on raptors and related topics. Data collected on raptors contributes to a regional picture of hawk populations generated from data collected at similar sites all over New England. About 3,000 raptors are sighted at the Hawk Watch annually.

If you can't make it to the park for the activity, check this page to see how many birds, and species, were sighted.

Since the Blue Ridge Parkway follows the Appalachian ridges for 469 miles, it attracts migrating birds and birders. Simon Thompson of Venture Birding Tours says that "any place where there's a gap, you're likely to see a good selection of birds on the parkway. Go early in the morning - the two hours after dawn is the best window of opportunity."

In North Carolina, Mills River Overlook at Milepost 404.5 is a popular place to watch the hawk migration. At Milepost 364.1, walk up Craggy Pinnacle between now and November to see broad-winged, red-tailed, and red-shouldered hawks, Cooper's hawks and sharp-shinned hawks.

The base of Mt. Mitchell at Ridge Junction Overlook, Milepost 355.3, at Black Mountain Gap is one of the best spots in the Blue Ridge to enjoy the fall migration of warblers and other passerines. Hawks pass through, heading south about the third week of September.

Continuing north on the Parkway, Mahogany Rock in Virginia at Mile Post 235 has a long history of excellent hawk watching in September and October. The spot recently lost its full-time watcher but people still gather here including the Blue Ridge Birders.

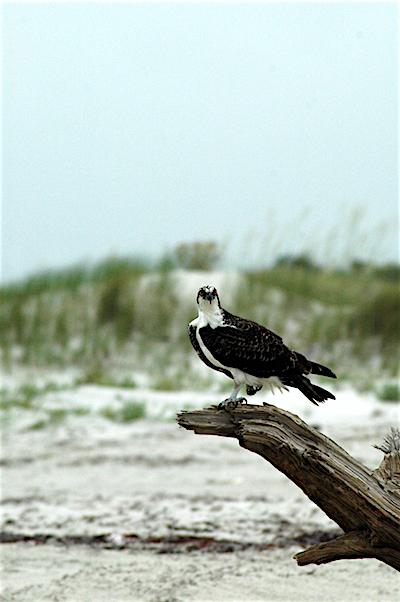

Osprey are among the bird species you might spot at Cumberland Island National Seashore/NPS

Cumberland Island National Seashore

Cumberland Island off the coast of Georgia is a favorite stopping point on the migratory flyway. More than 335 species of birds have been recorded at Cumberland Island National Seashore. A list of birds is available at the visitor center.

Doug Hoffman, the biologist at the seashore, notes that roseate spoonbills and even white pelicans can be seen from the boat on the way to the island. Once on the island, the freshwater pond areas provide excellent rookeries for wood storks, white ibis, herons, and egrets. In the forest canopy you can also see warblers, buntings, wrens, and woodpeckers.

On the shores, osprey, peregrine falcons, and occasionally bald eagles and golden eagles are spotted. Wild turkeys are plentiful on the south end of the island where the ferry lands. They're protected, so they're not skittish.

In the Dry Tortugas located west of Key West, Florida, fall migration is more prolonged than spring migration and is not as obviously influenced by weather. Large flights of raptors are common during September and October before slowing down by about late November.

According to park officials, "A scant assortment of waterbirds, most notably gulls and terns, winter in the area." The park's website offers a bird list.

Wildlife in the Everglades becomes a bit easier to spy in the fall, as the dry season (which begins in December and runs into April) commences and wildlife head for waterholes.

The park is renowned for its birdlife, with more than 350 species seen in the park, and many head to the park during the dry season to hang out and nest.

In the fall, patient birders might be rewarded with a sighting of a rare short-tailed hawk. Only about 50-100 of these raptors can be found in the Everglades from October to late February, so you have to be in the right place at the right time....with a good deal of luck!

Other common species that show up in the park in fall include pied-billed grebes, brown pelicans, double-breasted and anhinga cormorants, great blue herons, little blue herons, black-crowned night herons, white ibis and a variety of ducks and shorebirds. Download a copy of the park's species list, before you go so you'll know what to look for.

Glacier seems to have almost every large mammal from elk to black bears and grizzly bears to moose. More frequently seen than the grizzlies, though, are the snow-white mountain goats that thrive on the steepest of slopes along the Continental Divide. These animals with their professorial goatees often can be seen in the meadows on Logan Pass and even on the trails to the Granite Park and Sperry chalets.

Sometimes you can spot bighorn sheep on the cliffs that run along the Garden Wall that follows the divide through the park.

Mountain goats are some of the picturesque animals at Glacier National Park/NPS

Glacier is a large park surrounded by other public lands that was created early enough (1910) to offer protection to these animals. With a lot of luck, you might see a wolf, mountain lion or lynx. Look at the park's mammal checklist to know exactly what to watch for.

Fall also is a great time to see bird migrations in Glacier. Many folks have learned to watch for golden eagles migrating along the Continental Divide fly-way in mid-October. These big birds fly south from Alaska and Canada along the west side of the Continental Divide. They're visible from Mt. Brown Lookout on the west side of the park. It's a steep hike (5.3 miles one way), but worth it to view hundreds of golden eagles headed south.

The folks at Grand Teton help you watch wildlife in the fall with its two-page flyer that discusses where visitors can find animals. The lush meadows nudging up along the northern shores of Jackson Lake attract mule deer and elk.

In Willow Flats, a marshy expanse right behind the Jackson Lake Lodge, you often can spot moose and elk. Pronghorns, similar to antelopes and known to be the fastest land animals in North America, might be seen at the southeast end of Jenny Lake or, better yet, along the sagebrush flats along the Snake River and surrounding Mormon Row.

In early September, the Moose-Wilson Road is pretty reliable for black bears, as they come to feast on the tasty hawthorn berries. The bruins are so fixated on gorging themselves that they pretty much ignore the cars on the road. Just remember that they're wild bears and keep your distance.

The Oxbow Bend stretch of the Snake River also is famous for its birdlife -- white pelicans, trumpeter swans on occasion, osprey and even bald eagles. Otters occasionally can be seen frolicking on the river banks here, and moose love this area, too.

Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Whether you're visiting Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Rocky Mountain National Park, or Olympic National Park, the best time to go in search of bugling elk is right around dawn or dusk.

In the Smokies, the elk rut is a relatively new phenomena, as these animals once were hunted to extinction in the region. A recovery program launched in 2001, though, has met with great success, growing the park's elk herds to about 135 animals and leaving biologists confident the elk can survive on their own without heavy management.

Your best opportunity to watch and listen to the elk runs from now until the end of October in the Cataloochee Valley on the southeast section of the park. Wild turkeys, too, are active and toms are strutting their stuff through the fields, their big feathers spread out.

Elk and turkeys aren't the only highly visible wildlife in the Smokies in the fall. Over on the western side of the park, in Cades Cove, deer can often be seen in the open fields. While bucks with large antlers keep weaker males away and attract a harem much like elk bulls do, deer don't bugle. Still, their antics during the rut is something to watch...and to keep your distance from.

Bears also call the Cades Cove area home, and in the fall they come down into the orchards for some fresh fruit.

Migratory birds also are popular to watch in the park. At higher elevations flocks of migrating broad-winged hawks often can be seen when the first cold front comes through during the first half of September. With the cold front, raptors follow the Appalachian Range, riding the thermals over land. The best vantage points include Newfound Gap, Clingmans Dome, Look Rock, and Indian Gap.

Sharp eyes, and good timing, could result in a sighting of a Stellar's sea lion along the coast of Olympic National Park/Ken and Mary Campbell via NPS

In Olympic, the Hoh Rain Forest is an excellent place to see Roosevelt elk. These animals don't migrate, preferring to stay in the Hoh area year-round and banding together in herds of around 20 females and calves. September is a great time to hear the bulls bugling.

Roam the rocky coastline of Olympic and, if your eyes are sharp and the weather favorable, you just might be able to see some of the park's marine life. The Olympic coast lies along the migratory path of both California and Steller's sea lions, according to park officials, who add that en route to foraging areas in the Strait of Juan de Fuca California sea lions feed in the coastal waters in the late summer and early fall.

"They haul out in masses on the abundant offshore rocks, amiably alongside their larger cousins. These whiskered creatures are often visible on the islands off the coast of Cape Flattery and Cape Alava, arriving in late summer or early fall, and often staying through spring," the biologists say.

Though elk in Rocky Mountain were hunted extensively, an almost disappeared by 1890, as people settled the Estes Valley, animals transplanted from Yellowstone just before the establishment of Rocky Mountain National Park in 1915 helped to rebuild the herds. Predators such as wolves and grizzly bears were hunted extensively in the area, which helped the swift growth of the elk population.

"Most of the areas where elk rut are in the open meadows which happen to be near roads so viewing the rut is easily accessible to visitors," says Kyle Patterson, the park's public affairs officer. "The best places to view and hear elk are Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park and Upper Beaver Meadows on the east side of the park and Harbison Meadow and throughout the Kawuneeche Valley on the west side of the park."

Ms. Patterson also suggests that, "(Y)ou may also see mule deer that have their mating season a little later in the fall. Bighorn sheep mate later as well, but they're more difficult to find."

White-tailed deer can be highly visible at Shenandoah National Park/NPS

In Shenandoah, the wildlife viewing in the Fall is about as rewarding as the leaf-peeping. Bears, deer, and migratory birds all are visible if you take the time to look.

Many folks come to Shenandoah specifically to see black bears, and as both Bob Janiskee and David and Kay Scott pointed out in years past, sows with playful cubs were the main attractions. The many old apple orchards established by homesteaders before they left for creation of the park can be bear-magnets, so be careful while you're hiking.

And white-tail deer seem almost tame, they're not. A doe will protect her young as ferociously as a grizzly sow does. You often can spot deer congregating in the fields by Skyline Lodge. Black bears and bobcats hide in the forest and are harder to see. Coyotes, an adaptable predator not native to the area, keep moving eastward.

While fall is a great time to watch wildlife in the parks, stay safe. Parks have various rules on how close visitors should get to wild animals. Approaching on foot within 100 yards of bears or wolves or within 25 yards of other wildlife is prohibited. If you change the behavior of an animal, you're too close.

Yellowstone overflows with wildlife -- moose, elk, pronghorn, bison, wolves, grizzlies, black bears, and so much more.

Of course, animals and birds haven't read this article so they might not be where people have seen them last. These are wild animals, so there's no guarantee you'll see anything when you visit. Study a park's website before you go and make the visitor center your first stop once you enter the park.

Bring your camera, your binoculars, and a field guide. Good luck.

Add comment