Creating national parks doesn't happen every day. Lately, it seems the quickest way to create one is to legislatively redesignate a national monument as a national park (See Pinnacles National Park). But it doesn't hurt to dream, does it?

Here are five picks from the Traveler for new national parks. We offer up these nominees without consideration to fiscal impact because once you start to consider the costs -- mainly economic costs, but also political -- the possible can become impossible. With that understood, we view the following locations as truly spectacular places that should be preserved for future generations.

* Wind River Range, Wyoming

The Wind River Range in west-central Wyoming visibly defines spectacular. With 40 peaks that soar above 13,000 feet, including the state's highest point at 13,809 feet, glaciers, grizzlies, elk, bighorn sheep, lakes and trout streams, this craggy range runs roughly 100 miles north to south and 30 miles east to west.

Currently managed by the U.S. Forest Service, the range contains officially designated wilderness and is one of the country's premier hiking and backpacking areas. The range also harbors the headwaters of the Green River.

You can lose yourself in the Winds for days on end, spot North America's largest herd of bighorn sheep, find challenging climbing routes, or fancy yourself as a latter-day mountain man.

* Sawtooth National Recreation Area, Idaho

This 756,000-acre NRA long has been considered for inclusion in the National Park System. Indeed, back in 1911 a group of women in Idaho called for such a move, according to a history of the NRA's creation.

Stanley Lake in the Sawtooth NRA. Photo by Fredlyfish4 via Wikipedia.

In 1960, then-U.S. Sen. Frank Church introduced legislation to have the area considered for park status, and six years later even introduced a bill calling for Sawtooth National Park, but local opposition derailed it.

This wide expanse of wild lures river runners, climbers, backcountry skiers, anglers, backpackers and more. Cyclists challenge themselves on attacking the highway over Galena Summit, while families carry on long traditions of camping at Redfish Lake.

New England needs another national park, and the one proposed for the North Woods would not just be gorgeous, but would benefit wildlife species such as Canada lynx, Atlantic salmon and the eastern timber wolf threatened with extinction for lack of habitat and protect the "wild forests of New England."

The hardwood forests, lakes, and rivers would help build a strong recreation sector that would pump money into the surrounding towns. The streams and lakes here long have been plied by canoeists.

Talk of creating such a national park extends back over two decades. Proponents, along with pointing to the natural resources that could be protected, believe the cachet of a "Maine North Woods National Park" would bolster the region's economy through businesses that cater to park visitors.

* Ancient Forest National Park, California and Oregon

With climate change under way, protecting migrational routes, and providing migrational routes, for wildlife and even plants is vital to help ensure their survival.

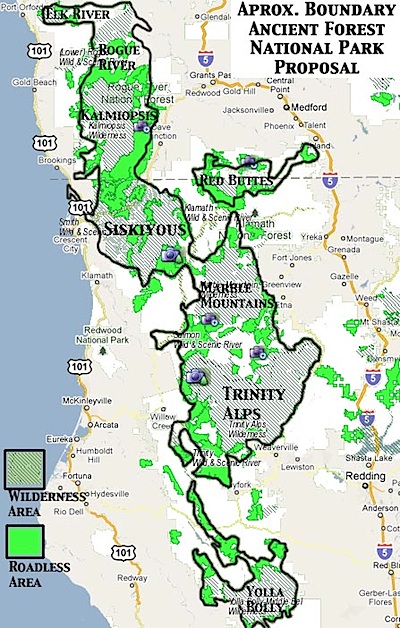

The boundaries of the proposed Ancient Forest National Park run from Oregon south into California.

Park Service Director Jon Jarvis back in August of 2011 called for establishing "a national system of parks and protected sites (rivers, heritage areas, trails, and landmarks) that fully represents our natural resources and the nation's cultural experience." He also cited the need for creation of "continuous corridors" to support ecosystems.

The proposed 3.8-million-acre Ancient Forest National Park spanning parts of southern Oregon and northern California would meet those goals.

Within its proposed borders there already exist officially designated wilderness and roadless areas, places perfect for both recreation and wildlife.

The proposal is to set aside a solid block of land 3.8 million acres from the Rogue River in Oregon to the Eel River in California. It will forever allow the free migration of species from the coast and Redwood National Park to semi arid inland canyons. The park would include already established wilderness areas and already designated critical wildlife areas along with about 1 million acres of unprotected inventoried roadless areas.

* San Rafael Swell, Utah

Talk of turning the Swell into a national park has simmered for decades, going back to the 1930s when local officials proposed a "Wayne Wonderland National Monument." The proposal went nowhere, for the Swell, but is pointed to as an impetus for Capitol Reef National Park.

Nevertheless, the wondrous landscape of colorful reefs of rock, deep canyons, and sandstone walls bearing ancient pictographs remain. So, too, do the tales of outlaws such as Butch and Sundance losing possees by galloping into the maze of canyons. Within the Swell you can find ancient granaries, stone arches, bald eagles, bighorn sheep, feral horses and mules, homesteader cabins, and old mining operations. There are opportunities for canyoneering, river running, backpacking and day hiking and more.

Today there are fewer and fewer pristine and preserved areas left in the country, a fact that has the clock ticking on the few remaining places that deserve national park status. While much opposition no doubt exists to each of the above proposals, they could be crafted in such a way to mollify many of the critics.

By creating a "national park and preserve," the enacting legislation could be written in a way to allow some traditional ways of life, whether they involve grazing livestock, hunting, or logging in a sustainable fashion. Communities could remain in place, with the "park-and-preserve" boundaries excluding them.

What other places do you think should be added to the park system?

Comments

When I first visited CUVA my first thought was indeed "Why is this a national park? The Hocking Hills are more scenic..." But I've come to realize that scenery is not the only metric that warrants a national park. In the ever-shrinking greenery between Cleveland and Akron, CUVA was in serious danger of being paved over. The history, natural features, and wildlife were at risk of being lost. National park status has halted the encroachment of civilization.

In spite of the patchwork of residences and businesses that permeate the margins, it's still easy to find solitude and beauty along the isolated trails, waterfalls and rock features. I've come to realize this "black sheep" of the NPS is no less important than any other. If land acquisition is in the works, this unique but battered area may one day be whole again.

It's easy to hate on CUVA because it's relatively small, lacks grandiose features, and is surrounded by cities. But at the same time it's sort of a blueprint for future national parks. Most areas with spectacular scenery are already preserved. Future parks will be those that feature unique historical and/or ecological importance that may be under serious risk of loss to development and exploitation.

muddymoose,

I couldn't agree more.

There are on pristine wild places left to save. Either we write off most of the country and sacrifice it to extraction and development, or we start patching together the pieces and restoring entire landscapes to health. There is still a lot to work with on that front.

CUVA is a good example of that. The work is not done there, but it is a great start.

From that National Park website:

"The wild, undeveloped areas of national parks (often called "backcountry") are subject to development, road building, and off-road mechanized vehicular use. National park backcountry is protected only by administrative regulations that agency officials can change. The Wilderness Act protects designated wilderness areas by law 'for the permanent good of the whole people.' With the Wilderness Act, Congress secures 'for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.'"

and

"Designated wilderness is the highest level of conservation protection for federal lands. Only Congress may designate wilderness or change the status of wilderness areas. Wilderness areas are designated within existing federal public land. Congress has directed four federal land management agencies—U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service—to manage wilderness areas so as to preserve and, where possible, to restore their wilderness character."

Places that were wilderness areas before they were national parks: Joshua Tree, Saguaro, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, Congaree, etc.

As for BLM, NFS, etc. not wanting wilderness areas, here is a list of proposed wilderness areas for 2013: http://www.pewenvironment.org/news-room/other-resources/wilderness-bills...

As I said, I love the National Parks. However, I think the priority should go towards getting as much acreage designated wilderness as possible. If you dis-include Alaska, only about 2.5% of our land is preserved as wilderness.

I guess, Michael Kellet, the difference between our points of view is that you are focused on the end result. I am focused on the first step to get there. I would rather see time and energy spent conserving and protecting as much land as possible as quickly as possible, rather than worrying about what status it eventually obtains. 1984 was a great year for land protection; I would like to see that repeated, though with our current congress, it doesn't seem likely. There is some positive news though: the Senate recently passed a slew of wilderness bills. Now we just have to hope some of them make it through Congress.

dahkota,

I think we are on the same side on all the important issues. You may have somewhat misunderstood what I said. I am not calling for national parks or nothing. I am glad for any increased protection. I am totally supportive of wilderness and have helped to pass wilderness legislation. I don't see it as an either-or proposition.

If I am understanding your point, I think you are saying that national parks are less protective than wilderness. It may be true that wilderness is congressionally designated, but national parks are also congressionally designated. And, despite the vague wording in the quotation that you included, the National Park Service has been protecting most parks as de facto wilderness longer than the Wilderness Act has existed. That is why more than 99 percent of our National Park System is unloaded, undeveloped wildland -- de facto wilderness.

Here is what National Park Service policies say about "The NPS Obligation to Conserve and Provide for Enjoyment of Park Resources and Values":

"The fundamental purpose of all parks also includes providing for the enjoyment of park resources and values by the people of the United States. The enjoyment that is contemplated by the statute is broad; it is the enjoyment of all the people of the United States and includes enjoyment both by people who visit parks and by those who appreciate them from afar. It also includes deriving benefit (including scientific knowledge) and inspiration from parks, as well as other forms of enjoyment and inspiration. Congress, recognizing that the enjoyment by future generations of the national parks can be ensured only if the superb quality of park resources and values is left unimpaired, has provided that when there is a conflict between conserving resources and values and providing for enjoyment of them, conservation is to be predominant. This is how courts have consistently interpreted the Organic Act."

— National Park Service Management Policies 2006, p 10-11 http://www.nps.gov/policy/mp2006.pdf

Regarding designated wilderness, I agree that it provides strong, congressionally mandated protection. However, there are loopholes in the Wilderness Act that allow some management practices that I do not consider consistent with wilderness. As I have noted, wilderness on National Forest and BLM lands allows livestock grazing, livestock-related range developments such as fences, corrals, water lines, and stock tanks, and mechanized access to maintain and construct these "improvements." Grazing is not allowed in National Park System wilderness. This is a huge disadvantage for leaving areas under the management of the Forest Service and BLM, versus transferring them to the National Park Service.

Moreover, to quote The Wilderness Society:

"The Wilderness Act is extremely permissive when it comes to controlling wildfire and allows agencies to take any such measure 'as may be necessary in the control of fire, insects, and diseases.' The Act allows great flexibility to suppress wildfires and reduce the buildup of hazardous fuels within wilderness areas."

—The Wilderness Society Managing Wildfires in Wilderness. http://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/Managing-Wildfires-in-Wilderne...

The Forest Service and BLM use this loophole to allow aggressive "management" activities,for "controlling" fire, insects, and disease, such as tree cutting, herbicide and pesticide use, and mechanized access. The National Park Service has used this approach minimally, except in some cases where there has been major political pressure.

Your list of "places that were wilderness before they were national parks," is technically accurate, if we are talking about National Park Service-managed National Monuments that were later redesigned as National Parks. However, my point was that they were all already managed by the National Park Service long before they were designated as wilderness. Being redesigned as National Parks had nothing to do with the fact they had been designated wilderness as Monuments. There are no lands that were designated as wilderness before they were National Park System units.

Your reference regarding BLM wilderness areas is a link to the nonprofit Pew Charitable Trusts website advocating congressional wilderness legislation. This is good news from the standpoint of political support, but does not refute my point that the BLM and Forest Service do their best as agencies to oppose and minimize wilderness designations.

For example, due to a lawsuit settlement by the Bush Administration in 2003, the BLM no longer designates any new Wilderness Study Areas. This is still the case, despite lawsuits by groups like Southern Utah Wilderness Association to force them to recognize millions of acres of roadless areas. The main impetus for the Wilderness Act was the fact that the Forest Service refused to permanently protect any roadless areas. After the Act passed, the agency dragged its heels until it was forced to study roadless areas with the RARE and RARE II processes, and in forest management plans. To this day, the agency draws the most restrictive possible boundaries for roadless areas. They are now even using technical loopholes in the administrative Roadless Area Rule to log in roadless areas in the White Mountain National Forest that are qualified for wilderness designations, and are likely to do the same in other forests.

I totally agree that we need to protect as much land as possible as quickly as possible. And I am absolutely supportive of more wilderness designations. However, only a fraction of federal lands qualify under the Wilderness Act's requirements. That leaves millions of acres of National Forest and BLM, state, and private lands unprotected from destructive resource extraction and development. Also, most of the remaining potential wilderness areas are relatively small and surrounded by exploited lands. Most of the acreage shown on the Pew website is actually National Conservation Areas, not proposed wilderness. They are certainly an improvement over the status quo, but they still allow harmful activities that would not be allowed in national parks or wilderness.

I support these designations where appropriate, but I am also for as many new National Park System units as possible. New national parks can be designated to encompass both roadless areas and lands degraded by past exploitation, to create a new restoration national park. That is how Shenandoah, Great Smoky Mountains, Big Bend, Theodore Roosevelt, and a number of other parks came to be. That is the only way we will ever protect areas east of the Rockies — and in most of the West as well — on a landscape scale.

Another advantage of national parks is that they are the most popular and well-known of all public lands. The 280 million people who visit the National Park System each year is a powerful potential force to advocate for new national parks. Unfortunately, there are few campaigns for new parks like the ones summarized in the Pew list. We need to change that.

Best,

Michael

It had protection when it was Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area.

The redesignation was about money and a wish to bring in more tourist revenue. While I suppose there's more funding, people aren't flocking in big numbers, and visitation is actually down from the time of redesignation. Their peak visitation years were before "national park" status.

https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%...

That's because most people know that Cuyahoga isn't a real national park. It truly does take away from other parks that could use the boost in budgets to protect more of it's resources. It should have remained as a NRA.

Most tourists are not going to spend the money travelling a 1000 miles to see that place, when you can just visit one of the state parks in your backyard and get a better natural experience. There never will be any great "buzz" on Cuyahoga being a great tourist designations. This is why I continue to state that there are only a few more national parks left to be designated in this country. The Cuyahogas, the Natural Bridge in Virginia, the High Allegheny are not going to attact the masses and will never be like the Smokies, Grand Canyon, Denali, etc etc. It's much better to make sure these places are protected, funded, and get wilderness designation, than it is to spread more funds around to more national parks that should have remained under the NFS or as a state park.

You make good points, SmokyMountainMan. I might disagree about High Allegheny, though.

I spent some time in the High Allegheny this year, and it would take a major donor like a Rockerfeller to establish that park properly. The problem is that a lot of private land surrounds that area. Seneca Rocks NRA is a beautiful place, and the Dolly Sods and the mountain that extends for 20 miles that is slated for natural gas development has potential, but it would require a massive financial undertaking to properly protect that area.

Its the exact same problem that Maine Woods is going through. The mosaic of private lands, and the want to maintain hunting on those lands is going to hinder it from ever happening.