Native American tribes, fur trappers, pioneers, and prospectors have all wandered around and within what is now a part of Lassen Volcanic National Park in California. Before it was a national park, though, the landscape consisted of two separate national monuments. It took a series of Lassen Peak eruptions between 1914 – 1917 to make national park establishment a “done deal.”

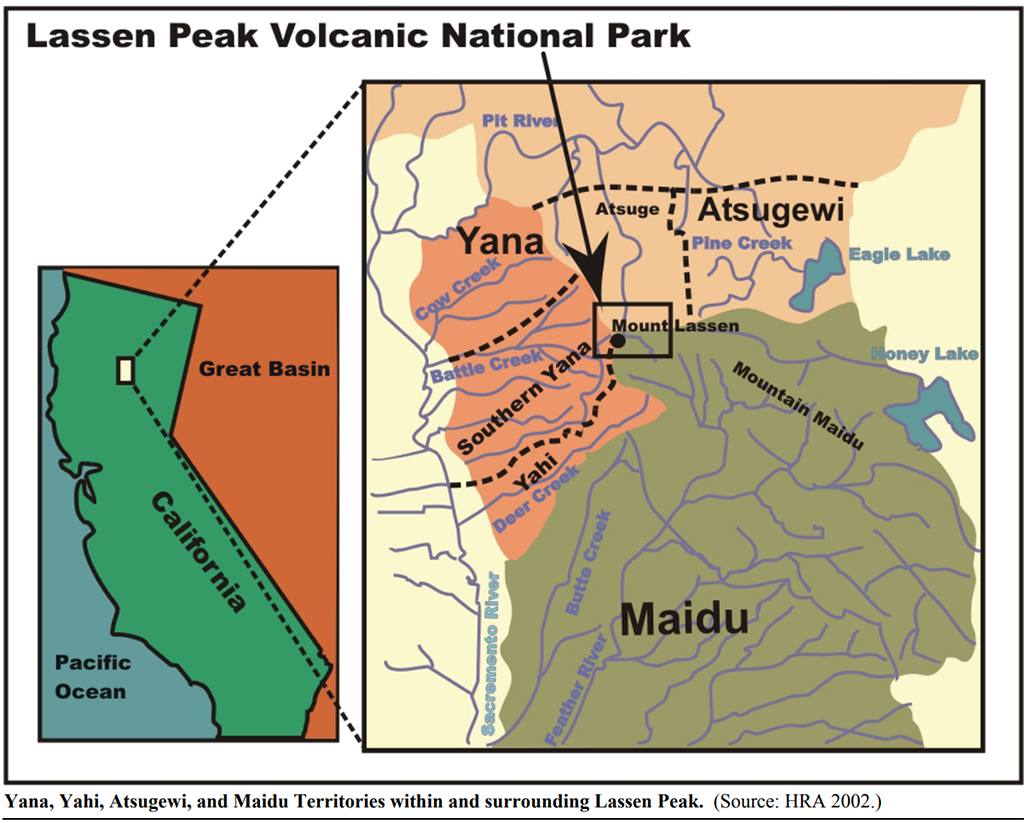

Territories of the four tribes living within the foothills of Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS

The high-elevation land encompassed within the boundaries of what is now a national park can be forbidding during the cold winter months. As such, there is only limited evidence of Native American habitation within the area, primarily within the foothills surrounding Lassen Peak, in territories established by the Yana, Yahi, Atsugewi, and mountain Maidu. Living in pit houses, bark lodges, and shade houses, but never settling into any permanent camps, the tribes moved from place to place for subsistence hunting (mainly deer), fishing, and foraging acorns, berries, roots, and greens, often trading food sources with the other tribes.

When fur trappers working for American and British interests began exploring northeastern California in the 1820s (then still a part of the Republic of Mexico), sporadic accounts of sighting Lassen Peak were mentioned. Neither trapper nor settler expressed any interest in inhabiting this thickly-forested, high-elevation area, and it wasn’t until 1844, when emigrant Pierson B. Reading obtained a Mexican land grant to settle in and found what is now the city of Redding, California, that any other incomers inhabited Lassen country.

Once pioneers and prospectors attended to the lure of gold, grazing, and fertile farmland reported to exist in California, wagon trails from east to west led emigrants along perilous journeys to a new land and new life. Between 1848 and 1851, two of these trails, the Lassen Trail forged by Danish blacksmith, farmer, and entrepreneur Peter Lassen, and the Nobles Emigrant Trail (aka Fort Kearney, South Pass and Honey Lake Wagon Road) established by Minnesota artisan William Nobles, led thousands of people to the promised land. These two trails skirted around or through portions of what is now Lassen Volcanic National Park. The Lassen Trail proved too arduous and was ultimately abandoned in favor of the Nobles Emigrant Trail, which merges with the Pacific Crest Trail through the north and northeastern sections of the park. Hike to the summit of Cinder Cone near Butte Lake and you can view part of this historic trail.

A view of park landscape from Cinder Cone summit, including a portion of the Nobles Emigrant Trail to the right of the photo, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

It wasn’t until the California Geological Survey’s establishment in 1860 that the geological uniqueness of Lassen country piqued enough interest to send out a survey team 1863. While exploring the area, the team scaled both Lassen Peak and Cinder Cone, returning home with stories of the diverse volcanic landforms, volcanic geology, and the wide variety of flora and fauna thriving within the area. Intrigued by these tales, other expeditions set out to explore this region.

Interest grew in logging Lassen country, but the expense of cutting and transporting the product from steep mountainside to market was prohibitive in comparison to the much less expensive coastal logging operations. In the 1870s, V-shaped flumes introduced an easier, more cost-efficient method of log transportation down from the mountains and to the railroad established between San Francisco, Chico, Red Bluff, and Redding. Fortunately for the land on which now sits the national park, continued lack of accessibility, combined with poor-quality timber, protected the forests there from being stripped bare.

Around the 1860s, grazing in the Warner Valley and meadows on the north and west sides of Lassen Peak proved successful and remained so until the establishment of the national park in 1916. Area landowners built retreats for vacationers wishing to escape the Sacramento Summer Valley heat, and began guiding groups on tours of the hydrothermal features in the region, including Bumpass Hell, so named after Kendall Vanhook Bumpass accidentally plunged his leg into a boiling mudpot while guiding a party.

According to the National Park Service:

The redemptive powers of the hot springs, the splendor of Lassen Peak, the beauty of the forests, and the enveloping quiet. Increasingly, the physical and spiritual redemption offered by mineral springs, mountain vistas, and mountain trails defined the area’s principal economic value. Recreational use and development, and conservation measures, continued apace.

Tourists near a hot spring at Bumpass Hell, ca 1930s (the park no longer allows off-trail hiking in the area), Lassen Volcanic National Park / NPS - George A. Grant

In 1905, the National Forest Service was established and Louis A. Barrett, supervisor for Lassen National Forest, surveyed the region. Keeping in step with his superiors’ desires at the time, Barrett proceeded to encourage railroad, power company, and sawmill development. Barrett did, however, also recognized the value of establishing federal protections around unique portions of the Lassen landscape such as Cinder Cone, and Lassen Peak. The only way he could achieve this was to assure his superiors the sparse and barren nature of those particular “natural curiosities,” as he termed them, contained no other commercial potential, and interested only “tourist, camper, scientist, and pleasure seeker.”

As a result, on May 6, 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt established Cinder Cone National Monument and Lassen Peak National Monument, thus preventing commercial development by private interests (except where prior valid claims existed), and protecting the land for future generations. These national monuments were managed by the Forest Service.

Petitions circulated for instituting a larger national park with boundaries encompassing a wider spread of the region around these national monuments. They languished until a series of Lassen Peak eruptions began in 1914. Newsmen, tourists, and scientists converged on the area to witness the beginning of a 3-year eruptive period (1914 – 1917). Photographer Benjamin F. Loomis began chronicling the eruptions with his camera, later displaying his photograph collection in a museum he founded in what is now a portion of the national park near Manzanita Lake, and which also serves as a summer visitor center.

Lassen Peak erupting in 1914, prior to the establishment of Lassen Volcanic National Park / B. F. Loomis Photograph Collection

On May 22, 1915, Lassen Peak experienced its greatest eruption, spouting a mushroom-shaped cloud 4 miles (6.4 km) into the air and depositing several inches of volcanic ash as far away as Reno, Nevada (>100 miles / 161 km). Loomis photographed the eruption and its aftermath, and eye witness accounts added emphasis to this monumental event.

During these eruptions, support for establishing a national park preserving these volcanic wonders grew more vocal, particularly by one John Raker.

According to the National Park Service:

Congressman John E. Raker of California, who was more instrumental than anyone in the establishment of Lassen Volcanic National Park, exemplifies how preservationists and conservationists were often indistinguishable. Raker worked for legislation to create the National Park Service, and in 1912, he introduced his first bill to establish a “Peter Lassen National Park.”

Raker re-introduced bills to establish a national park in 1913 and 1914 but he could not find much support for them in Congress [until Lassen Peak erupted in May 1914]. “We have suddenly developed a scenic wonder in northern California that is in a class by itself,” wrote one of the campaigners for the national park in June 1914. Lassen Peak was then the only active volcano in the contiguous United States. Combined with the scenic attractions and the variety of volcanic features, the area now possessed the kind of superlative qualities that Congress looked for in establishing national parks. As Yard would write a few years later, “the national parks are far more than recreational areas. They are the supreme examples. They are the gallery of masterpieces.”

In December 1915, Raker introduced another bill to establish a national park. Emphasizing the recent eruption, the name was changed from Peter Lassen to Lassen Volcanic National Park. After minimal discussion, the bill passed both houses of Congress in July 1916 [and] President [Woodrow] Wilson signed the bill into law on August 9, 1916 [combining Lassen land with existing Cinder Cone and Lassen Peak monuments.]

Creation of Lassen Volcanic National Park was not the end of things, however. At one point, this national park was almost abolished when the United States entered World War I in 1917 and stockmen strongly advocated for unlimited grazing within the park. The stockmen and the public siding with them reasoned this would further success of the war effort by producing more meat for the soldiers. Stephen T. Mather, then director for the newly-minted National Park Service, sent NPS representatives to address the local public and convince them tourist recreation dollars would amount to greater economic success than grazing within national park boundaries ever could. Ultimately, their arguments won the day, helped by money Congress began providing for park development. By 1925, the issue of overgrazing within the park disappeared.