Heritage presenter Wanita Stone stands in the visitor interpretation center at Red Bay National Historic Site in Labrador. The site explores the area's whaling history/Jennifer Bain

In a tiny fishing village in Labrador, the story of the heyday of Basque whaling is told through ancient whale bones and terracotta tile fragments that still lie scattered along the coastline. But, to be honest, you really need a good imagination to fill in some of the blanks.

When I arrived at Red Bay National Historic Site, I went straight to the Parks Canada visitor interpretation center where heritage presenter Wanita Stone eagerly showed off tiny vials of whale oil, one purified and one naturally rendered and so stinky it had to be taped shut.

She stood by a replica “tryworks” that shows where whale blubber was once rendered into oil in large copper cauldrons set on stone “firebox” ovens. The open-air shelters were held up by wooden posts and covered with red clay tiles brought over from Europe as ballast to give stability to the whaling ships.

“You’ll see the tiles along the shoreline when you go to Saddle Island,” Stone promised. “There’s still lots over there.”

Fragments of European roofing tiles from the Basque whaling area can still be found on Saddle Island, part of the Red Bay National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

Red Bay is considered the earliest, most complete and best-preserved example of early industrial-scale whaling in the world. The national historic site is part of the larger Red Bay Basque Whaling Station, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that includes bluffs around the harbor, islands, shoreline and a buffer zone in case of future archaeological finds.

During the mid-16th century, an abundance of whales drew men from the Basque region of Spain and France to the Strait of Belle Isle, where they established a major whaling port at Butus (later renamed Baie Rouge by the French and finally Red Bay by the English). For 70 years, Parks Canada explains, whalers made a dangerous spring journey across the Atlantic to hunt whales and produce the oil that lit the lamps of Europe.

The North Atlantic right whale and Greenland right whale (better known as the bowhead) were slow moving, easy to approach, floated when killed and yielded plenty of oil and baleen. Highly prized whale oil burned brighter than vegetable oils, and was used to make soap, paint and varnish Baleen — fringed plates that hang in the mouth of filter-feeding whales — was used for corsets, hoop skirts and other consumer products that required elasticity.

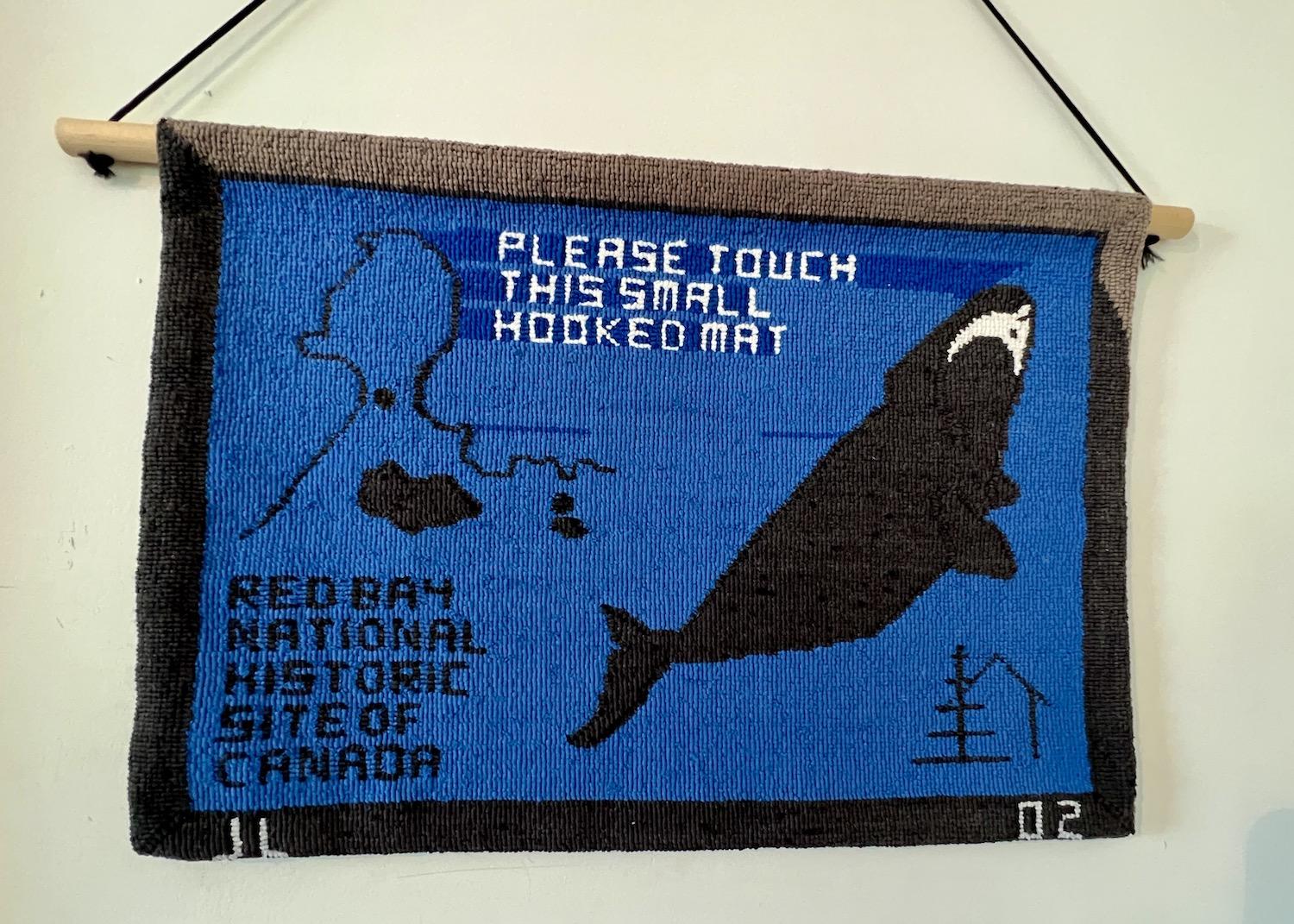

A hooked mat that shows a right whale is on display at the Red Bay National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

When the whalers arrived, they mainly lived on their ships and their coopers would immediately start to assemble wood barrels that had been brought from Europe in pieces to save space. They set up scaffolding to dry codfish and built stone ovens to prepare oil. The rendered oil was transferred to cold water to further purify and cool before being poured into barrels and stored on the ship for the return voyage to Europe.

During the peak whaling decades, nearly a thousand men worked out of Red Bay alone.

By the final years of the 16th century, Basque whaling in Canada began to decline due to overhunting, climate change, the discovery of new whaling grounds at Spitsbergen, Norway and changing political circumstances.

A portrait of historian/geographer Selma Barkham hangs at the Red Bay National Historic Site because she helped reveal the history of Basque whaling in Canada/Jennifer Bain

From there, the whaling story slowly faded away for more than 400 years until Canadian historian and geographer Selma Barkham’s diligent work kick-started archaeological research at Red Bay.

From 1977 to 1992, numerous digs took place on land and underwater. Archaeological research unearthed the remains of 20 whaling stations along the shore. Underwater research led to the discovery of three Basque galleons and several small boats. The biggest finds were the San Juan, a Basque galleon that sank in 1565, and pinned beneath it a smaller boat known as a chalupa.

This chalupa, about 26 feet long and almost seven feet wide, is considered one of the greatest achievements in marine technology. Designed to handle strong tides and high winds, this ingenious row boat held a crew of seven — one steersman and six oarsmen, including harpooner — that pursued whales that were triple the size of their wooden vessel. They towed their catch back to the ship or to shore.

The chalupa, a Basque whaling boat, found in Red Bay Harbour is on display at Red Bay National Historic Site — but in a building that won't reopen to the public until 2025/Jennifer Bain

Spanish shipbuilders are now making a replica of the San Juan, which went down with barrels of rendered whale blubber aboard. The chalupa, which was found in pieces, was reconstructed, restored and returned to Red Bay.

It’s now in a new visitor orientation center that is slated to open in the next year or two and replace the current visitor interpretation center. Kirby Ryan, a heritage presenter, unlocked the door of the new climate-controlled building so I could get a sneak peek at the oldest living boat of its kind, which sits on rocks behind a bowhead's lower jaw bone.

Ryan also unlocked the town hall during my July visit to show off the Red Bay Right Whale Exhibit featuring the articulated skeleton of a bowhead whale recovered from local waters in 1985. The exhibit brings right whales to life, detailing, among other things, how they filter huge volumes of ocean water through their baleen plates to capture crustaceans, krill, small fish and zooplankton.

The skeleton of a right whale is on display in the Red Bay Town Hall/Jennifer Bain

“Our whale is over 400 years old and would have measured well over 50 feet in length when it was alive,” interpretive signs revealed. “Human contact with `Rights’ has been disastrous for the species. Centuries of commercial whaling and decades of accidental deaths through fishing gear entanglements and collisions with ships have pushed Right Whales to near extinction.”

As I raced the clock to catch a ferry back to the island of Newfoundland, there unfortunately wasn’t time to walk the Boney Shore Trail on the southern side of the harbor to a beach named for the whale bones left behind by Basque whalers. But I did make it to the trailhead and read with interest that it’s illegal to remove bones from this UNESCO-protected area.

What there was time for was a boat ride to Saddle Island, which is part of the national historic site and included with admission. The tiny island in the harbor is home to important archaeological sites that contain the remains of rendering ovens, cooperages to assemble barrels, wharves, temporary living quarters and even a cemetery with mass graves.

Parks Canada heritage presenter Kirby Ryan stands on Saddle Island by signage about tryworks from the Basque whaling era in Labrador/Jennifer Bain

That's not to say you actually see all those things.

Along a boardwalk, which passes a small pond as it cuts across the island, about a dozen intrepretive panels helped paint a picture of the Basque whaling era. There were views of Red Bay, whose population has dwindled to 140, and icebergs floating in the distance. Sticking out of the water were the rusted remains of a coal-carrying ship called the Bernier that sank in 1966. But other than a few ducks, gulls, wildflowers, indentations in the grass and one magnificent pile of red tile fragments, there was little to actually see.

"When they were excavating, they catalogued roughly 25,000 artifacts underwater and about the same on land," Ryan explained. "What we don't have on display, there's stuff in the Rooms (museum) in St. John's and stuff up in Ottawa for study purposes."

Saddle Island, once home to seasonal Basque whaling activities, faces the village of Red Bay and a rusted shipwreck from the 1960s/Jennifer Bain

As we walked, we had to dodge a construction zone since part of the boardwalk was being redone. The intention for 2024 is to build a replica tryworks, cooper's building and other things to give visitors — currently about 12,000 a year — a better sense of what's here. Costumed interpreters could then be stationed at strategic spots.

I did fine with Ryan's insight and by cross-referenced everything I saw with a bilingual Parks Canada pamphlet called the "Basque Whalers of Red Bay: A Sweeping Tale of Whales, Ships and Men." It folds out with a map of Saddle Island and short descriptions of a dozen stops, like the whale oil rendering ovens, cooperages, San Juan wreck site, wharf, whalers' cemetery and even the footprint of a "mystery building" that some suspect was a chapel.

"You've got to use a lot of imagination to try and figure it out," Ryan quietly acknowledged before we hopped in the shuttle boat for the quick ride back to the mainland.

While You're In Labrador:

A plaque, several interpretive signs and a viewing platform can be found at L'Anse Amour National Historic Site/Jennifer Bain

Most people take the ferry from St. Barbe, Newfoundland to Blanc Sablon, Quebec, which is minutes from the Labrador border. From the ferry terminal it’s a one-hour drive to Red Bay. About 25 minutes into that drive, take the turnoff to L’Anse Amour to see L’Anse Amour National Historic Site. Pull to the right at a tiny loop to a small wooden viewing platform. You’ll see a mound of rocks that is the earliest known elaborate grave site in North America. It marks the burial place of a Maritime Archaic child who died about 8,000 years ago.

Discovered by archaeologists in 1973, the body was covered with red ochre, wrapped in skins or birch bark, and placed in a large five-foot-deep pit. Fires were lit on either side of the body, and stone and bone spearheads of stone were placed beside the head. A walrus tusk, harpoon head, paint stones and bone whistle were also placed with the body. The burial mound forms part of an ancient, multi-component archaeological site occupied by the Maritime Archaic people between 9,000 and 2,000 years ago. The 116-acre site — which also goes by the names L’Anse Amour Funerary Monument and L’Anse Amour Burial Site — contains the remains of many small seal hunting camps.

The provincial border sign for Newfoundland and Labrador is near the ferry terminal in Blanc Sablon, Quebec/Jennifer Bain

Add comment