Field scientist Josh Pons releases a weather balloon from the deck of the Viking Octantis while in Lake Superior in June/Jennifer Bain

It was just after breakfast somewhere on the Canadian side of Lake Superior when we gathered midship on Deck 6 of the Viking Octantis and waited to be escorted to the “secret” Deck 7. Would the wind scuttle things again or would the scientific highlight of an expedition voyage through the Great Lakes finally happen?

Upstairs, we obediently gathered behind the winch point — marked by a giant yellow circle painted on the deck — as the ship’s science team prepared a helium-filled latex balloon tethered to a radiosonde transmitter and sensor unit.

The countdown began just shy of 8 a.m. Ten seconds later, field scientist Josh Pons released the white weather balloon to great applause and we gaped as it shot briskly skyward and was engulfed by blue sky above the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area.

“Oh look, here comes an F-16,” one wise-ass shouted, referring to the fighter jets that the United States Air Force scrambles when facing immediate threats in restricted airspace. Technically, Canada scrambles CF-18s, but everyone got the joke and the balloon could eventually drift south of the border.

In the science laboratory of the Viking Octantis, field scientist Josh Pons shows off a biodegradable weather balloon/Jennifer Bain

Of course, Viking had permission from the U.S. National Weather Service for the launch to measure temperature, humidity and pressure data to help with weather forecasts, climate modelling and storm prediction. The cruise line partners with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory for the project.

As our balloon ascended out of sight through the troposphere into the stratosphere, it transmitted data back to a receiving station on the ship.

The flight would reportedly last about two hours and the biodegradable balloon would climb up to 20 miles, more than tripling in size until it popped, sending the battery-powered radiosonde back to the ground by parachute. That package would hopefully be returned and reused thanks to a mailing bag and instructions.

Meteorological bodies have long overseen the daily ritual of weather balloons rising simultaneously around the world. But for civilians on Octantis, it was a rare chance to see how scientists collect essential data for global weather predictions and climate modelling.

On that June morning, we were invited to leave Deck 7 (which is usually off limits and doesn't show up on the ship's interactive deck plan) and head to “Expedition Central” to see the weather data arriving in real time, but I had a submarine to catch — yes, really.

At Expedition Central on the Viking Octantis, field scientist Josh Pons shows weather balloon data to a guest/Jennifer Bain

Viking, founded by Norwegian billionaire Torstein Hagen and headquartered in Switzerland — arrived in the Great Lakes in 2022 after a long history of ocean and river cruises. Octantis — named after Sigma Octantis, the south star — is its first expedition ship. Her identical sister Polaris is named for the north star. Both purpose-built, ice-strengthened ships travel all five Great Lakes and Antarctica with 378 guests and will soon add Arctic routes.

Never mind the Nordic spa with a sauna and snow grotto, heart-shaped Norwegian waffles from a treasured family recipe and free self-serve laundry room, Octantis has a wet/dry science lab with a sample processing area, fume cupboard, freezer and cool storage, comprehensive microscope optics, and extensive bench space for analysis-specific instruments.

Like all expedition cruise lines, Viking brings along experts like field research scientists, general naturalists, kayak guides, ornithologists, geologists and biologists. Unlike most competitors, it even has sub pilots.

Jessica Burnell pilots a submersible when the Viking Octantis is on the Canadian side of Lake Superior, near Pyritic Island, in June/Jennifer Bain

"It's really nice and calm today so we've got it easy," Jessica Burnell said excitedly as six of us took turns climbing from a Zodiac to the floating platform of a small yellow submarine named — wait for it — John. Viking has four subs and the others have naturally been dubbed Paul, George and Ringo in a nod to the Beatles and their iconic 1966 song.

Keep in mind, this was early June before five men would tragically die taking the Titan submersible to a depth of 12,000 feet in the ocean off Newfoundland to see the Titanic shipwreck. We were vaguely nervous but pumped to immerse ourselves in Lake Superior without needing to be scuba divers.

We had been weighed so John would be properly balanced. We had been scrutinized for overt or latent signs of claustropobia. We had been warned to wear sensible shoes and remove earrings, rings and watches so as not to damage anything. We had been briefed on what to do if our pilot fell unconscious (wait for the sub to automatically surface within minutes, but know that there was also enough food, water and oxygen to survive for four days). We had carefully gauged the weather and were in constant contact with a dive support boat and the bridge of the Octantis.

Viking submersible pilot Jessica Burnell sits in the center of "John" with three guests on either side of her pilot seat and controls/Jennifer Bain

Viking's dives last just 30 minutes and don't visit shipwrecks. The compact subs were built to dive to 985 feet but never go deeper than 330 feet. They have been certified by DNV, one of the world’s leading maritime classification bodies. The Norwegian-flagged Octantis can't deploy submersibles in U.S. waters due to complicated protectionist laws originally designed to regulate maritime shipping, but it is allowed to dive in Canadian waters and so picked a spot near Silver Islet just off Pyritic Island.

Wearing special booties, we gingerly descended down a ladder from the hatch into the double bubble-designed vessel to assigned seats that swivel beside spherical windows.

Burnell, a free diver from Cornwall, England, talked us through the details of the dive as they happened. "It was always a dream to pilot subs — I never thought it would happen," she confided as she carefully guided us down about 190 feet in front of a rock wall. We stayed about 12 feet off the bottom of Lake Superior to ensure the multi-million-dollar sub didn't touch anything.

Viking guest Bob Palmer, from Florida, enjoys Lake Superior from his seat inside a six-passenger yellow submersible named John/Jennifer Bain

The murky water shone green at the surface and darkened as we descended, and it felt like I was a kid swimming at the cottage without having to hold my breath. So what did we see? Just that rock wall, a hint of a sandy/rocky bottom and a single fish, yet we all left giddy.

I was seated beside Bob Palmer, a retiree from Florida with a PhD in marine biology who spent 12 years as the Democratic staff director of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Science. Like the rest of us, it was his first time in a sub.

"I think it met my expectations," Palmer confided. "I mean, I wasn't expecting it to be stunning with anemones and sea stars and all that. But the patterns, I thought, were really interesting. The sedimentary patterns and all the different colors of the different depths. Even though you're not seeing a lot of biology, it's still interesting."

The Viking Octantis anchors in Lake Superior just off Sleeping Giant Provincial Park in Ontario, where three dragonflies dot the June sky/Jennifer Bain

Even with the benefit of hindsight, the sub dive was the undisputed highlight of the week-long Great Lakes Explorer route that took me from Milwaukee to Thunder Bay across Lake Michigan, Lake Huron’s Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. But each day brought memorable experiences.

In the U.S., I took a carriage ride on historic Mackinac Island and stood on deck as our ship squeezed through the Soo Locks. In Canada, I learned about biodiversity, bees and species at risk at the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve in Parry Sound, and hiked in the Canadian Shield around Killarney and Frazer Bay. I climbed Casson Peak, a place that inspired one of the founders of Canada’s renowned Group of Seven landscape painters, but also the trail where I saw my first oak apple galls, a mysterious, vaguely apple-like growth produced on oak twigs by a tiny wasp. The female lays her eggs in the leaf bud. The gall is filled with chambers that contain larvae that eat their way out.

Still, something about Lake Superior — the largest, coldest and most remote of the Great Lakes — resonated. Called Gichigamiing or “the Big Lake” by the Anishinaabe people of the region, Lake Superior is known for its furious storms and is often referred to as an inland ocean. This complex international water body is administered by the governments of Canada and the United States, the province of Ontario, and the states of Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan.

I turned to iNaturalist to identify this oak apple gall, an apple-like growth on the twig that's produced by a tiny wasp/Jennifer Bain

We didn't experience anything resembling a storm as we sailed Superior. Nor did we visit the famous wreck of the SS Edmund Fitzgerald, a freighter that sank during a 1975 storm killing 29 men and was later immortalized in a Gordon Lightfoot song. But it was on this lake that I watched my first weather balloon release and safely rode my first sub, and for that I am grateful.

I also seemed to be the only person to realize that we were traveling through the Lake Superior National Marine Conservation Area.

Once fully established by the Canadian government, the Lake Superior NMCA will be one of the largest protected areas of fresh water in the world. It covers about one third of the Canadian side of the lake — or one eighth of the entire lake — plus some peninsulas and islands. It's funded and operating as Parks Canada delivers programs at Terrace Bay and Nipigon and figures out how to promote a water-based protected area. At some point, though, cruise ships will likely need permits to do the things we did.

In Sleeping Giant Provincial Park, tour guide Tom Boland (a Thunder Bay teacher with a home in Silver Islet) shows a driftwood log embedded with a rusted spike/Jennifer Bain

One night at happy hour, I chatted with Jørn Henriksen, Viking's director of expedition operations, about the rules surrounding sub dives and why the company expanded from ocean and river cruises into expedition cruises. He enthused about how science gives the operation purpose beyond tourism, and how being a scientific platform is an important marker of an expedition ship. "It's about giving back to the places that we sail to," he explained. "It's about giving back to the global community. And it's about also communicating science to a broader population."

Besides, Henriksen noted, Viking's adult-only passengers are "keenly interested and intelligent" people who are often decision makers and leaders in their home communities. "Science is important to us, and it's important that we are rigorous and that we're not only doing show-and-tell science, if you like, but that the baseline components of science that we do are something that actually contributes."

Henriksen also provided a tour of the Hangar, an enclosed in-ship marina full of expedition “toys” and my favorite place on Octantis. The subs are kept here alongside polar-tested kayaks, a fleet of Zodiacs and two 12-seater convertible Special Operation Boats (cheekily dubbed SOBs and apparently also used by Norwegian special forces). There's a slipway so guests can embark on SOBs shielded from wind and waves from a flat, stable surface inside the ship if the conditions are too challenging outside.

Jørn Henriksen, Viking's director of expedition operations, shows off the "toys" (kayaks, Zodiacs, submersibles and Special Operations Boats) in the Hangar of Octantis/Jennifer Bain

But Lake Superior gave us no trouble and neither did the late spring weather.

On the weather balloon day, the Octantis anchored off the cottage community of Silver Islet between Pyritic Island and Sleeping Giant Provincial Park, home to an iconic flat-topped mountain that resembles the silhouette of a sleeping person when viewed from Thunder Bay.

I went to shore on a tender boat and took a gentle, guided hike to the Sea Lion rock formation, a natural arch that resembled a lion sitting on its haunches until its head eroded and fell into the water. Guided by Tom Boland, a Thunder Bay teacher with a home in Silver Islet, I learned about the geology and history of the area. Then I strapped into a seat on a SOB to see the Sea Lion from the water, ogle a nesting bald eagle, and circumnavigate Trowbridge Island, home to a lighthouse.

A view of Trowbridge Island Lighthouse in Lake Superior not far from Silver Islet/Jennifer Bain

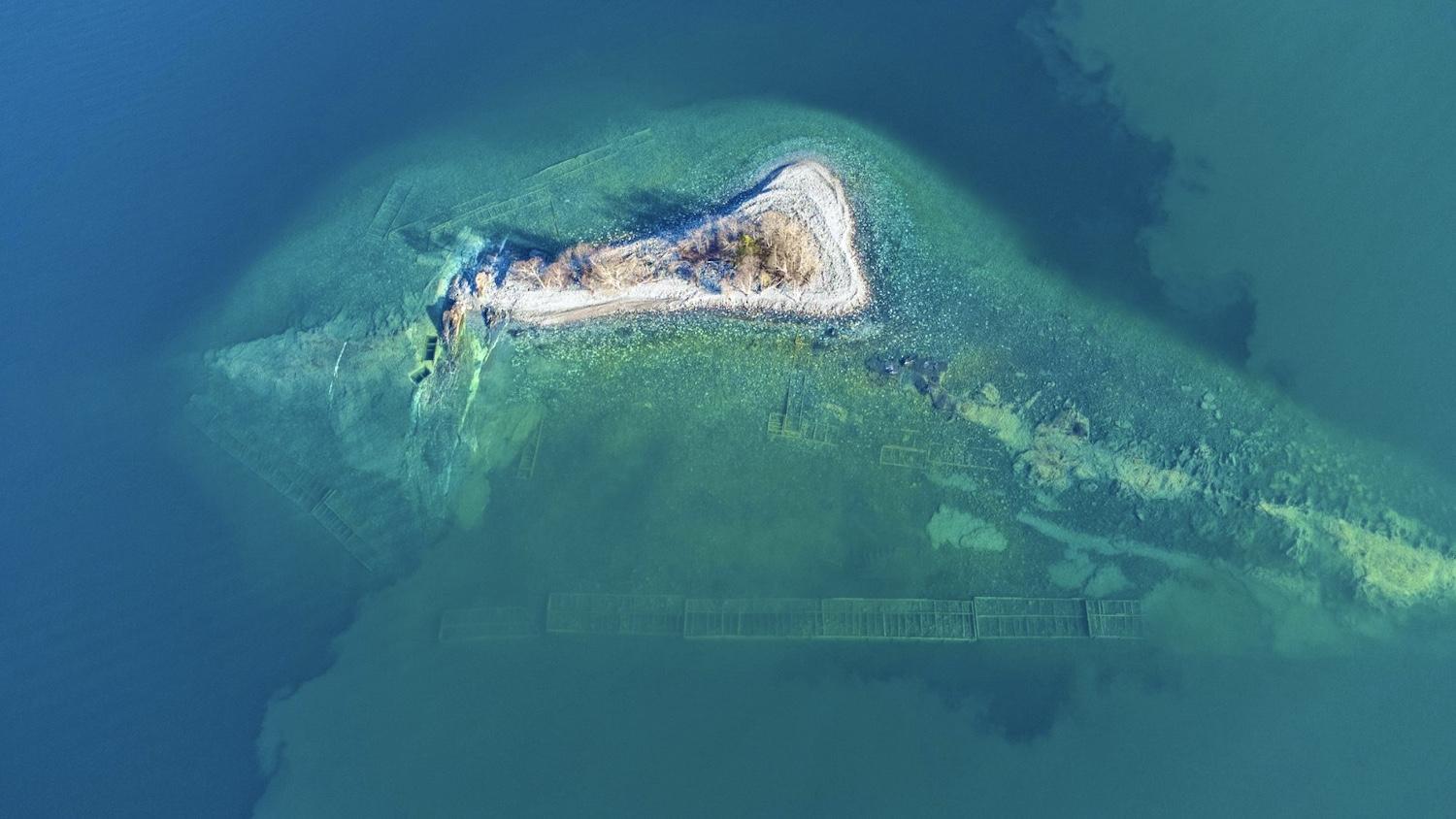

There unfortunately wasn't time to go ashore at Trowbridge, but the SOB paused off a speck of a barren island called Silver Islet where miners once excavated silver ore deep under Lake Superior. This was the world’s richest silver mine for 14 years until 1884 when a coal shipment failed to arrive to keep the water pumps running and the shafts flooded. Today all that remains are the tops of underwater shafts that can only be seen by boat. The island is privately owned.

That night, weary from an intense day of learning on Lake Superior, I thought about something Pons said when we toured the lab and discussed how much guests can learn on the Great Lakes expeditions. "It's really nice to get more and more people involved with science," the marine biologist said. "Some people, they never studied science, they have no background in science, maybe they did just a completely different career choice their whole lives, right? But by the end of it, they're pleasantly surprised by how they can contribute and how they can be involved — and people leave feeling like scientists."

I definitely felt like a citizen scientist, at least, as I retreated to my stateroom. I uploaded some things I'd seen to iNaturalist, an online community where people share photos of plants and animals while generating data for science and conservation. Then, as directed, I closed the blinds on my floor-to-ceiling windows so my lights wouldn't attract migratory birds crossing the Great Lakes. Viking, guided by advice from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, had already entered "bird safe lighting mode" to reduce the chance of birds striking the Octantis.

An aerial shot of what was once a booming underwater silver mine near Silver Islet in Lake Superior/Viking

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places

Support Essential Coverage of Essential Places