Rick Ridgeway started his life of adventure at 18, when he joined a group of friends to sail a small boat to Tahiti. Over the next half-century, he enjoyed (and survived) more adventures across the world than most of us can even conceive of.

A decade later, he met Yvon Chouinard, who in turn introduced him to Doug Tompkins, and these three legendary outdoorsmen, mountaineers, and conservationists became the core of the self-styled “Do Boys.”

“We don’t just talk about doing stuff,” Yvon said. “We do it.”

And did they ever! Life Lived Wild is Rick Ridgeway’s memoir, but much more than that it offers stories of pathbreaking adventures and adventurers, details a love story embracing family, friends, and the natural world, and is an introduction to a historic moment in environmental conservation. Ridgway is a compelling writer, and the book is a wonderful read.

Ridgeway shares 25 stories of his adventures that span remote corners of five continents, describing triumphs, disasters, a pantheon of fellow travelers, and many lessons learned and personal insights gained over the decades. In the Acknowledgements at the end of the book, he admits that his friend Candace Davenport, who joined him for a misadventure early in his career, advised him that the draft he had sent her to review, comprised of 50 stories, was way too many. Ridgeway agreed, and halved the number, admitting that the draft “was so long it was more doorstop than memoir.”

Life Lived Wild, at 25 stories, is more than 400 pages, so that was probably a good decision, although he is such a good storyteller and has such spellbinding tales to tell that many readers would have enjoyed more, doorstop or not.

Davenport also told Ridgeway that he should be more open about himself, and he must have taken her advice because the book is very revealing. Life Lived Wild is no hard-man account of conquests but is a sharing of his fears and self-doubts, of aspirations, and especially of his love of adventure, of wild places, of friends and family.

There is an intimacy to his writing style that, after reading the book, makes me think I know him though he and his fellow Do Boys have, for modest adventurers like me, lived in an elevated world far beyond most of us. He writes with humor, salting funny anecdotes about the Do Boys and others with whom they shared their adventures. He describes, for instance, how he met journalist Tom Brokaw after his K2 climb. The Today Show wanted an interview with someone from the expedition and no one else was willing.

At the NBC studios in Rockefeller Center, the escort who met me at reception looked surprised. That was understandable. I had on an aloha shirt – the only thing I had when we got back to civilization that wasn’t shredded – and a pair of billowy Pakistani pants I had bought in the Rawalpindi Bazaar. I wore flip-flops because of blisters on my feet. I hadn’t had a haircut in five months. The skin on my face was peeling, and the cracks on my lips hadn’t yet healed, so blood ran down my chin when I smiled. The studio escort reached out to shake hands but recoiled when she saw my fingers, black from frostbite.

In the green room I was introduced to Jane Pauley and Tom Brokaw. Jane raised her eyebrows and Tom grinned. I had been told that Brokaw would be the one to interview me.

“I can guarantee you,” he said, “there’s never been anybody to come on the Today show looking even close to the way you do.”

Ridgeway and Brokaw became lifelong friends, and Brokaw joined the Do Boys for some adventures and earned honorary status in that august group.

Over the decades, influenced by his Do Boy compadres Chouinard and Tompkins, by scientists like George Schaller, by enjoyment of and amazement at the natural world he traveled, and by a growing awareness of threats to that world, Ridgeway became a conservationist. Urged by his wife Jennifer to take the opportunity to have “a regular job,” something about which he had reservations - he had been self-employed as a self-styled “adventure capitalist” throughout his career - in his mid-50s he joined Chouinard’s Patagonia company to run its sustainability and environmental initiatives.

In one revealing story he describes serving on the National Geographic Expeditions Council that reviewed grant proposals for its Young Explorers program. One proposal titled “Path of the Pronghorn” was from a 21-year-old photographer named Joe Riis. Ridgeway was so impressed by Riis' proposal, which was to follow the annual 150-mile migration of pronghorn antelope from Grand Teton National Park to the Red Desert in southwestern Wyoming, that he urged that National Geographic not only give Riis a grant, “but allow me to go with him on his trek. After all, every twenty-one-year-old needs a mentor.”

At this stage of his career, Ridgeway enjoyed supporting someone “coming up through the ranks.” He had done so with Jimmy Chin, and he did it for Joe Riis with remarkable results. Riis innovatively used camera traps to intimately document pronghorns and other wildlife and publicize the path of the pronghorn, inspiring increased attention to the need to protect migration corridors for wildlife.

I mention this because, while Life Lived Wild is full of adventure stories with big names in mountaineering and other adventure sports –- Chris Chandler, John Roskelley, David Brashears, Galen Rowell, Conrad Anker, Jim Donini, Chris Bonington, and Will Steger of polar adventure fame, among others -- Ridgeway grew beyond the sports he loved and association with the experts. He became a writer, filmmaker, photographer, and ultimately conservationist, and sought to help others who aspired to follow his path into the “wild.”

When Joe had first been awarded his Young Explorers grant, senior photography editors at National Geographic wanted to send a seasoned photographer to cover his trek following the migration. I had gone ballistic, asking them how they could expect to bring up a new generation of photographers if they didn’t give them a chance to take ownership of a project, especially a project that, in this case, Joe had proposed? They finally backed off and allowed Joe to photograph our trek himself.

Rick could join and enjoy the adventure of a young colleague, teaching and mentoring as he and Riis tracked the path of the pronghorn. This account of his advocacy of Riis is revealing of how Life Lived Wild goes beyond a collection of adventure stories.

But adventure stories abound. Ridgeway travels to Minya Konka, is nearly killed, and loses his friend Jonathan Wright in an avalanche. After this, thinking perhaps as a family man he should not risk his life like this, his wife Jennifer convinces him to be the adventurer he is, and he helps Dick Bass and Frank Wells organize and mount their Seven Summits adventure, joining them on some of their climbs, most notably on the Vinson Massif in Antarctica.

Ridgeway also travels to Everest, but does not make the summit; climbs K2 with John Roskelley; and drags a high-tech rickshaw across the Chang Tang “Big Open” in northwest Tibet with Galen Rowell, Conrad Anker, and Jimmy Chin on an expedition inspired by George Schaller to document the 300-mile migration of a threatened ungulate called the chiru. He tries to travel across Borneo, becoming seriously ill there, and joins an expedition to Bhutan on which the party can’t even reach their unclimbed objective, Gungkhar Puensum. Lovers of adventure stories will be very satisfied with this book while likely craving more detail on some of the stories, which they can find in some of Ridgeway’s previous books.

The Chang Tang trip was inspired by Rick’s need to do more for conservation and “Using my mountaineering and adventuring skills to try and help save an endangered species seemed like just what I should be doing with my life.” He describes how, in his early 50s, he decided to go in some new directions.

I had successfully sold my photo and film agency to focus on making films about outdoor sports, but that wasn’t as fulfilling as it had once been. I had written a book about my trip with Asia [Wright] to find her father’s grave, and I felt good about that. But I was watching my friends increasingly dedicate themselves to wildland and wildlife conservation, and I felt inspired to do my part. Doug and Kris (Tompkins) were busy buying estancias in Argentina and Chile, and Yvon was doubling down on Patagonia’s commitment to environmental protection, giving away 1 percent of the company’s sales – not profits, but sales – to environmental nonprofits, so that rain or shine, good year or bad, the company was paying what Yvon called its “Earth tax.”

Ridgeway went to work for Patagonia, and much of the latter section of the book describes the remarkable work of Doug and Kris Tompkins in Argentina and Chile where, over two decades, they managed to buy up land, establish national parks, and gift the parks to Argentina and Chile. The Tompkins, along with Chouinard, were Rick’s closest friends, and he celebrates their achievements. Tragically, on a kayaking trip on Chile’s Lago General Carrera with Chouinard and others, Doug Tompkins died in an accident, and Ridgeway was nearly lost as well. In a gripping chapter titled “That Unmarked Day on Your Calendar,” Ridgeway tells the story of this disaster and his narrow escape.

Life Lived Wild is full of friendship and love. After decades of shared adventures, losing Doug hit the surviving Do Boys hard, to say nothing of how it affected Kris. Rick’s wife Jennifer helps Kris through this difficult time, and Kris goes on to complete the work she and Doug had been working on for so many years. Then Rick loses Jennifer to cancer. Of this, Rick writes “I don’t believe in the idea of closure. It is a misguided response to death. It is healthy to face toward, rather than turn away from, the gap left by the death of someone you love, even as you face the pain of no longer hearing the voice of the one you loved in your ears while you continue to hear the voice in your mind.”

Some may think it strange to characterize this book as such, but I think Life Lived Wild is a love story. Rick’s love for Jennifer and his children, for the Do Boys, for Kris, for his lost friend Jonathan Wright and Wright’s daughter Asia, for the mountains, the chiru, the young adventurers coming up, permeates the book.

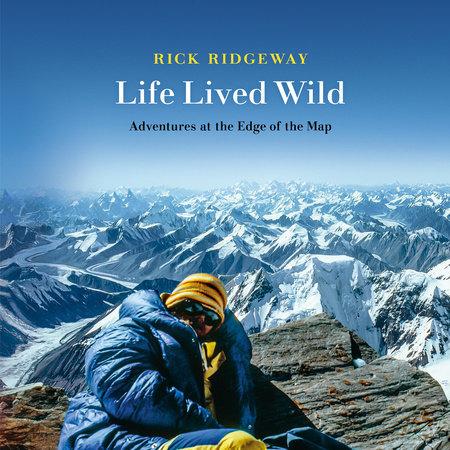

Like all Patagonia Books, Life Lived Wild is a superb publication, full of excellent photographs crisply produced on the page, the layout fine in all respects, a wonderful map inside the hard covers highlighting the locations of the 25 stories Rick tells. The front cover features a photo by John Roskelley of Rick on the summit of K2 on the first American ascent of this difficult mountain, and the first ascent without oxygen. The cover is enough to entice the armchair adventurer to dive into the book where they will be rewarded with much more than they anticipate.

Get this book and pass it around. Perhaps even adopt the philosophy of the Do Boys, to not just talk about doing stuff, but to do it for oneself and the world, especially the wild world.

Add comment