The untouched beauty and unusual rocks of the Hog Island Sandhills in Prince Edward Island/Epekwitk Assembly of Councils

Editor's note: The L'nuey organization reports the community is shifting to a different Mi’kmaq word for the area — Pituamkek instead of Pitaweikek. It means "At the Long Sand Dune."

The coronavirus pandemic has slowed plans to protect Prince Edward Island’s last coastal wilderness, but work is being done to finally launch the public input stage surrounding a proposed national park reserve in a chain of barrier islands.

The Hog Island Sandhills stretch 50 kilometres (30 miles) along the northwestern coast of the province and include a coastal dune ecosystem and a rare igneous rock outcropping formed when molten rock cools and crystallizes. The islands are home to species at risk like the little brown bat, northern long-eared bat, piping plover and gypsy cuckoo bumblebee, and threatened species like the bank swallow, Canada warbler and common nighthawk.

The islands have long been special to the Mi’kmaq people and contain cultural and archaeological sites. Hog Island, the largest of the islands, is known as Pitaweikek (bed-DAH-wey-gek) — a Mi’kmaq word meaning “tea broth place” that will eventually be incorporated into the park name.

The proposal is unusual because it was the Mi’kmaq Confederacy of Prince Edward Island that first asked Parks Canada in 2005/2006 to protect the area by making it a national park, and then continued to work on the plan despite initially being rebuffed.

“It’s a bit of a unicorn situation in Canada, for sure,” says Tracey Cutcliffe, senior negotiator at L’nuey. “There was a strong desire by the Mi’kmaq to protect the area.”

The Hog Island Sandhills are a chain of barrier islands off the northern coast of Prince Edward Island/Epekwitk Assembly of Councils

L’nuey is leading the negotiation and engagement for the protection of Pitaweikek on behalf of the Abegweit First Nation and Lennox Island First Nation. It’s a new Mi’kmaq rights-based initiative formed by the Epekwtik Assembly of Councils to protect and preserve the constitutionally entrenched rights of the Mi’kmaq people on P.E.I.

When the Mi’kmaq community originally proposed Hog Island as a national park to Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, it already had a good working relationship with Parks Canada through Prince Edward Island National Park and Jesse Francis, who has worked on culture and heritage projects since 2005 in a job that’s an unusual partnership between the Mi’kmaq Confederacy and Parks Canada.

The Conservative government “took a pass on the proposal,” remembers Shanna MacDonald, Parks Canada’s senior negotiator for protected areas establishment and manager for national park establishment in Southern Canada. The country is divided into eco-regions and the goal was to set up a national park in each. Since Prince Edward Island National Park and New Brunswick’s Kouchibouguac National Park already existed in the same eco-region, Hog Island Sandhills wasn’t a priority.

But the Mi’kmaq continued to do environmental, geological and archeological studies and assessments while working with the provincial government and environmental groups. In 2017, with Canada now under Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government, they reapproached the federal government, through the federal environment minister, and got the green light.

“Pre-Trudeau the focus was on eco-regions,” acknowledges MacDonald. “Now there has been a shift into areas where we know we have strong support and are able to move ahead.” The Liberals have also pledged to protect 25 per cent of Canada’s land and 25 per cent of Canada’s oceans by 2025 — and to work toward 30 per cent in each by 2030 — to recover species at risk, fight climate change and provide Canadians with more places to discover nature.

After months of behind-the-scenes work, Parks Canada announced August 14, 2019 that a Hog Island Sandhills feasibility assessment would be done and that it would work with the Mi’kmaq Confederacy, government of Prince Edward Island, Island Nature Trust and Nature Conservancy of Canada.

“We propose to protect and preserve this special place, including its nature and its cultural site,” Lennox Island First Nation Chief and Mi’kmaq Confederacy Co-Chair Darlene Bernard said in a news release at the time.

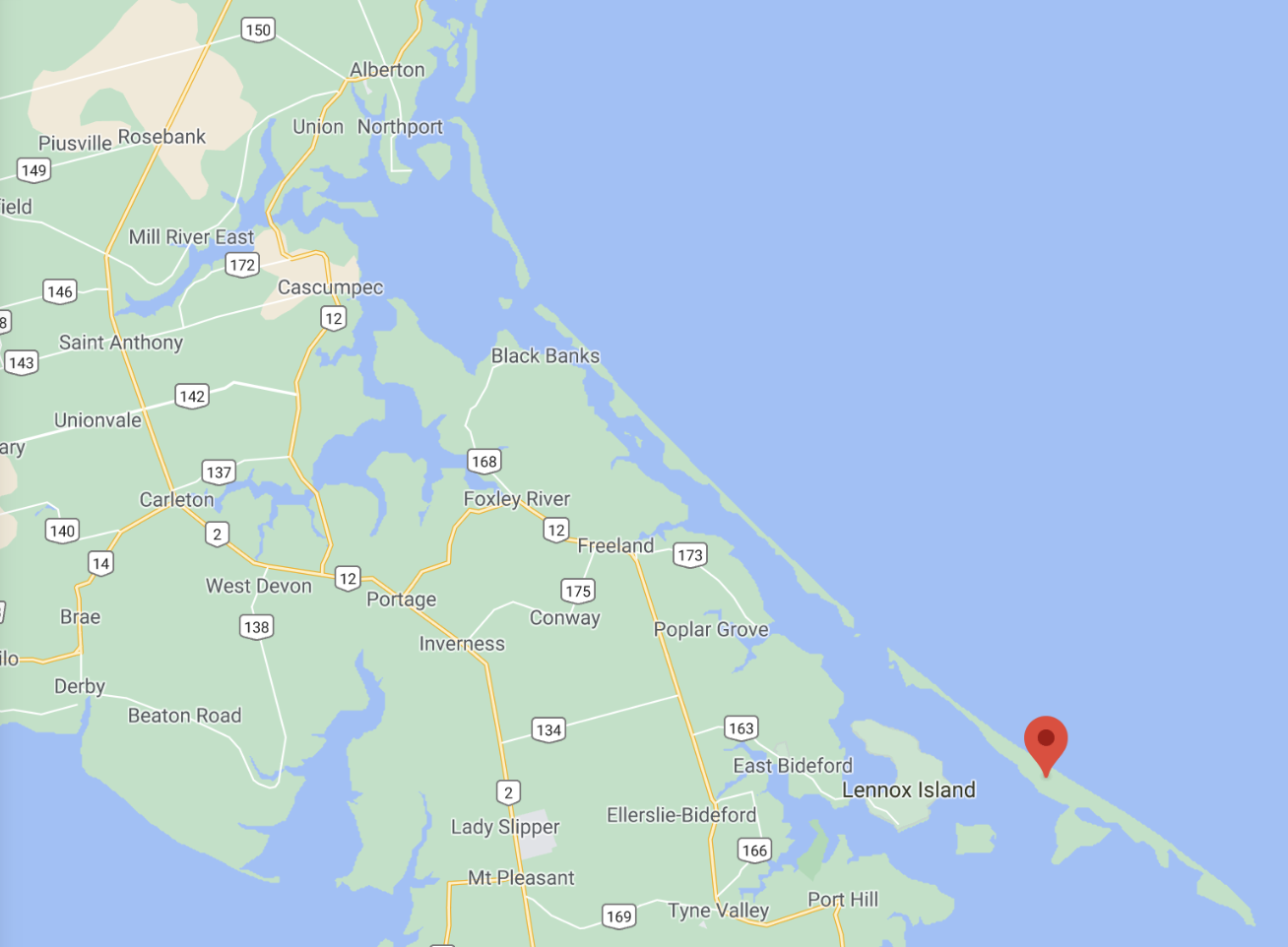

The Hog Island Sandhills are made up of three large, sand-based islands and several smaller ones that loosely stretch from the Alberton/Northport area to just south of Lennox Island. The feasibility study will define and recommend the size and scope of the proposed national park reserve, and see whether it should include the entire chain or just Hog Island. It will consider the social, environmental and economic benefits. There are a few parcels of land held by non-Indigenous individuals, and locals have long used the islands for recreation.

In late 2019 and early 2020, plans were afoot to start gathering input from stakeholders, the community, locals and Canadians. Pamphlets, questionnaires and PowerPoints were being drafted, web material written, and venues booked — and then COVID-19 hit.

“It was kind of a hard stop” at first, recalls MacDonald, with hope that things would soon return to normal. “Then it became obvious that the severity of the pandemic was going to disrupt our traditional ways of engaging with the Indigenous community and the local public.” Meetings couldn’t be held face-to-face, nobody wanted to put Indigenous elders or other people at risk, and not everyone has computers, internet or reliable Wi-Fi.

MacDonald is now “hopeful that we’ll have some form of virtual presence in the spring.”

After public input, the next step would be to finalize a Memorandum of Understanding that lays out things such as the co-management terms as well as the new park reserve’s name. “Hog Island Sandhills is what most people have referred it to over the years,” says Cutcliffe, “but there will be a Mi’kmaq name.” Work is underway to confirm the correct spelling and pronunciation of Pitaweikek.

The final step would be a land transfer agreement and an establishment agreement. “It’s tough to commit to a timeline,” says Cutcliffe, “but I can say from the Mi’kmaq leadership perspective, they’re speaking in years not decades.”

While every national park and national park reserve plan moves at its own pace, MacDonald says this one is unique because it was launched by an Indigenous community that did much of the legwork. “Because of that level of commitment and that level of interest, we already have the province and the local Indigenous community saying `we think this is a really good idea.’ Now we need to hear what public concerns might be raised.”

Hog Island (with a red marker) and the other barrier islands that surround it/Google Maps

The word “reserve” at the end of a national park or national marine conservation area name signifies there is an active land claim in that area between the federal government and the Indigenous community. That claim often involves defining Indigenous harvesting rights and might result in removing a portion of the land.

“A national park reserve is on paper the same as a national park and everything about it is under the National Parks Act,” says MacDonald. “Everything is still treated as a national park.”

In this case, the Mi’kmaq Confederacy is negotiating with Ottawa to settle a Specific Land Claim for Hog Island (which includes George, George’s Sand, Fish and Bill Hook islands). It says the government bought the islands in 1942 from the Lennox Island Band — now Lennox Island and Abegweit First Nations — but failed to turn it over to reserve land.

Lennox Island first filed the specific claim in 1996 but it stalled in a dispute over whether the government’s breach of fiduciary duties happened in 1942 or 1968. Lennox Island and Abegweit refiled the claim in 2012 with additional evidence. In 2016, Canada accepted the claim for negotiation and agreed the date was 1942. Negotiations begin in October 2017. The two key issues are replacement lands and/or compensation for the reserve lands that weren’t transferred in 1942, and compensation for the loss of use associated with the lands since 1942.

Without naming the proposed national park reserve, the Mi’kmaq Confederacy notes in a community summary that “the parties have also been in discussions regarding the best possible way to ensure the lands are protected, with First Nations stewardship, now and for future generations.”

Northern long-eared bats are one of the species at risk on the Hog Island Sandhills/Parks Canada

Parks Canada’s mandate is to “protect and present nationally significant examples of Canada’s natural and cultural heritage.” While access to the Hog Island Sandhills for Mi’kmaq cultural or rights-based activity “will absolutely be factored in” to the creation of a national park reserve, according to Cutcliffe, there’s no word yet on how tourism will be handled.

“It’s a sensitive landscape,” stresses MacDonald. “There are lots of archaeological remnants there that are very important and very disturbable. We’ll figure out what we think the landscape would be able to handle.”

Canada only has 47 national parks — plus one national urban park — and so it’s rare to potentially get to see how one is established from start to finish.

Counting Hog Island Sandhills, Parks Canada is studying seven potential national parks and marine and coastal areas. Work is being done on a final boundary and governance approach for the South Okanagan-Similkameen National Park Reserve in British Columbia. Feasibility assessments are continuing for five proposed national marine conservation areas in the Arctic Basin (Ellesmere Island), southern Strait of Georgia, Southern Gulf of St. Lawrence adjacent to the Îles de la Madeleine, eastern James Bay and Northern Labrador.

Add comment