How did these two coins, believed to be Spanish pieces dating to the 13th century, get to Glen Canyon NRA?/NPS

Spanish explorers and wayfarers traveled across the Southwest, and through present-day Utah, 250 years ago, but what is the chance that one dropped some coins along the way while resting near the river we know as the Colorado? Or, in light of the estimated dates of the coins, were they trade pieces passed along going back two centuries more?

With two time-weary coins in hand, that's the mystery Brian Harmon hopes to solve.

The coins came to light late last year when a hiker near Halls Crossing in the middle of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area spotted two bits of dingy metal on the ground in an area that was somewhat littered with garbage. The Colorado man, who has asked to remain anonymous, thought the two coins were recent trash. It was only after he got home and took a closer look at them that he realized he might have two pieces of the past, the long ago past.

"When he picked them up he didn’t think that they were anything significant," Harmon, the NRA's archaeologist, said Tuesday during a phone call. "In fact, he was quite aware of the cultural resource protection laws that we have in place. So when he picked them up he thought they were just some sort of cool modern thing. And it was only when he took them back home and got a closer look that he realized that these were old Spanish coins."

Old indeed.

“The expert that we’ve been working with says that it looks like one coin (called a 16 Maravedis) was minted in Madrid, Spain, probably in 1662 or 1663," the archaeologist said. "The smaller coin of the two, the visitor did some Internet research, and thinks it's probably mid-to-late 13th century. Doing some Internet eyeballing on my own, I kind of agree with that, but neither he nor I are coin experts."

Two coins, possibly 400 years apart. Found on the same patch of ground.

“By my way of thinking, there are three possibilities here," Harmon replied when asked how the coins possibly got there. "And any of those could actually be the case. The most exciting one is that these coins were actually brought there by some early Spanish settler or explorer. Which would be very exciting, because there’s really no strong evidence of early Spanish in this part of Glen Canyon. We do know that Dominguez and Escalante came through in 1776, trying to find a way from Sante Fe to California, but other than that, there’s just almost no other evidence for that sort of early Spanish presence here.”

And when Dominguez and Escalante came through there area, they were quite distant from the Halls Crossing area. First they tried to cross the Colorado River near today's Lees Ferry, explained Harmon. Then they went a bit north, towards the Wahweap area, and crossed at a place known today as the Crossing of the Fathers, he added.

“There is no reason at all to think these are associated with Escalante and Dominguez, because they weren’t anywhere near there, and that was 1776 and these coins aren’t anywhere near that date," the archaeologist added.

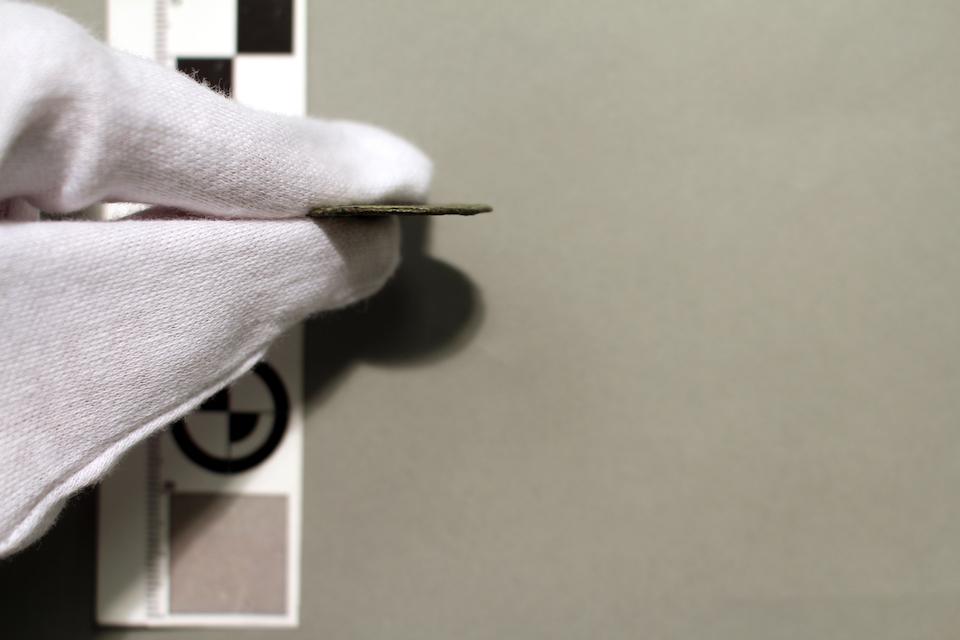

Side profile of a Spanish coin believed to date to 1660s found at Glen Canyon NRA/NPS

Now, explorers tend to wander. In the mid-1500s, around the 1540s, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado spent two years leading an army north from Mexico into the Southwest, crossing today's Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas, in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Gold. While Coronado's main route didn't take him and his force into Utah, one spur off the main route led to the Grand Canyon, and it's not terribly hard to envision some of the force breaking off from there to search on their own.

To Harmon's way of thinking, though, the coins possibly had been used in trade.

"The second possibility is that these coins were traded by, again, early Spanish settlers or explorers, to some Native American group, or individuals, who then either carried them to this location, or the coins were traded down the line," he said. "And essentially got here through Native American hands, which is also a really neat story if that were the case, because it sort of captures one more interaction of these two cultures coming together, or multiple cultures coming together.”

Of course, in light of the great disparity in the dates of the coins, if they were used for trade, they were passed down through the generations to whoever lost them near today's Halls Crossing.

Perhaps the most reasonable explanation is the least interesting, and most distressing, possibility.

“The last possibility, which is very unexciting but cannot be ruled out at all, is that these coins in fact are a modern deposit. Because they’re such two different dates, 1600s and probably early 13th century, and because when the visitor found them he described a lot of modern trash and garbage in the area that would be associated with things coming off of houseboats and/or land camping. There is a very real possibility that these things were modern," said Harmon. "That someone’s coin collection was either intentionally or accidentally lost.

"Like I said, we cannot rule out that possibility," he went on. "I know it seems strange. If I had 17th century Spanish coins, I wouldn’t take them out of my house.”

The archaeologist dismissed the thought that the coins were imitations that were "salted" in the NRA to attract attention.

“I was thinking of that same possibility, and it occurred to me this is probably the worst possible way to perpetrate a hoax, because it’s two coins, and only two coins, radically different dates, in the context of modern garbage, modern trash," said Harmon. "I think the coins are legit, and they got there through non-nefarious means.”

Soon Harmon and some other park staff will head to the area where the coins were found and search for additional traces of the past.

"The things that we’d be looking for is, first of all, are there other coins there? And second, are there places nearby that these coins could have eroded out of or washed down from? For example an alcove, especially one that had other cultural material in it," the archaeologist explained. "If that is there, then we can start thinking about ways to target that location or multiple locations and see if we could find out anything. Would we be able to recover any material from there that would be of similar age to either of these coins, or the early Spanish presence in the Southwest? If there is no place nearby that looks like a sort of source for these coins, then it becomes much more likely that they were deposited here fairly recently. That’s how I’m thinking about it right now."

Harmon also is thinking what a great thing it was that the Colorado man called the Park Service after he realized he might have two bits of the long ago past.

"One of the first things that he did, he realized that, ‘Wow, these could be really important, I need to get ahold of Glen Canyon,’" said the archaeologist. "So he gave us a call right away, and he said, ‘Hey, I found these, I didn’t realize what they were, but now that I know what they are I want to do the right thing and make sure they get back to you.'"

The last thing park staff want is for a rush of visitors armed with metal detectors to descend on the park. That's one reason why they're not being overly specific about where the coins were found.

“Even though this is a really cool and exciting find, obviously, we don’t want people to get so excited that they head out with metal detectors or similar things. Because, one, it’s illegal in the park, and secondly, preserving history for everyone is what we encourage and do in the National Park Service," Harmon said. "So when people find things we really encourage them to report it to a ranger. We’ll be happy to go out and look at things, but leaving things in place is always the way to go.”

Comments

I came across this article today and was quite intrigued. I've been wanting to find ancient coins along the Colorado River for many years now. Readers of the book, "The Little Book Cliff Railway: The Life and Times of a Narrow Gauge Railway" may very well remember the section of the book where a few cowboys broke into the safe in William Carpenter's office at the railroad depot in Grand Junction, Colorado and made off with his collection of ancient coins. One of the thieves was caught after trying to pay for a meal at a local farm west of town with one of the coins, but the collection was never recovered.

Are these part of that collection perhaps?