Squawking, chirping, and peeping fills the air but mist obscures the birds as we slowly paddle under a gentle rain through bergs cast off by the Marjorie Glacier. The ice drifts by in various sizes and shapes, some whimsical, others stable roosts for seabirds taking a break from the sky.

We've left behind the Sea Wolf, our 90-foot-long, World War II-mine-sweeper-turned-mothership, and set off in kayaks to get closer to the glaciers that lie at the head of Tarr Inlet on the northern end of Glacier Bay National Park.

Neither the Marjorie nor Grand Pacific glaciers are going anywhere quick. While Grand Pacific "grounded out" some years ago and no longer calves into the inlet, it still backs up about 35 miles into the St. Elias Mountains. But Marjorie, a mile-wide river of ice at the inlet with a snout some 250 feet high and a length of about 20 miles, is dependable for those hoping to watch ice cleaving off and toppling into the water with a booming rifle-shot crack.

Yet despite the lure of these ice-age remnants, the birds quickly have become the main attraction.

Black-legged Kittiwakes, Arctic terns, Glaucous-winged gulls, puffins, marbled murrelets and many other species swoop, wheel, and dive all around us from their perches on the rocky, waterfall-laced cliffs rising above the inlet's west shore. We crane our necks and heads back and forth at the darting birds, dipping our paddles into the icy waters to push the kayaks this way and that just to hold them in sight.

A Kittlitz's murrelet at takeoff. Photo by Scott Gende, NPS.

One Nerf football-sized bird that is hard to spot, and is trending more and more difficult to see as the years pass, is the Kittlitz's murrelet (Brachyramphus brevirostris). A cousin to the comparatively more prolific Marbled murrelet (Brachyramphus marmoratus) and the Long-billed murrelet (Brachyramphus perdix), the Kittlitz's murrelet is a roughly 9-inch-long, 7-ounce feathered conundrum that might be doomed by climate change.

It is a remarkable, glacier-reliant seabird that nests in amazingly inhospitable places and then goes north into the Arctic to winter.

Unlike nearly all other seabird species, the Kittlitz's murrelet does not nest colonially; pairs retreat from the saltwater to steep, rocky, remote slopes -- usually surrounded by glaciers -- to lay and incubate a single egg. And once summer ebbs, these murrelets -- like puffins and guillemots a member of the auk family -- spend the bulk of their time on the water, going ashore only to nest. As winter nears they don't head south with warmer weather, but rather head to the frigid waters of the northern Gulf of Alaska and even further north into the Chukchi and Bering seas.

"The species' natural history is just absolutely crazy, really. I mean, these non-colonial seabirds are linked somehow to tidewater glaciers, although not exclusively, and nest up in this radical nesting habitat,' Michelle Kissling, a wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service tells me, referring to the distant "nunataks," a native word for the craggy ridges and mountains surrounded by glacier and icefields.

"And then another interesting piece of their life history is that the species seems to migrate westward and north in the winter. Not south like the other smart birds," she says with a laugh. 'This one migrates west along coastal Alaska and then north, apparently meeting up with the sea ice edge in the winter months."

Until recently, not much more than that was known about the overall population and history of these diving birds. Dr. Scott Gende, a coastal ecologist for the National Park Service in Juneau, describes the Kittlitz's murrelet as "one of the least known bird species in the Northern Hemisphere."

"Until about six years ago there had only been about 25 nests that had ever been found globally, and only about three of those have actually been, quote-unquote, examined scientifically," he mentions at one point as we discuss the species and its plight.

Generally speaking, seemingly little has ever really been known about the Kittlitz's murrelet, which takes its name from Friedrich Heinrich Freiherr von Kittlitz, a German zoologist credited with capturing one of the birds during an expedition that navigated the globe between 1826 and 1829.

Kittlitz's murrelets cross daunting terrain in leaving the oceans and bays for nesting grounds. Photo by Scott Gende, NPS.

In a January 1936 National Geographic article, Birds of the Northern Seas, Alexander Wetmore wrote that while the species was common in some areas, 'Kittlitz's murrelet is so local in its range in American waters that few persons have seen it.'

'Specimens have been obtained in the Aleutian Islands, where in certain localities it is fairly common, and scattered individuals may be found in summer along the Pacific shores of the Alaska Peninsula,' he went on. 'In Glacier Bay, Alaska, at the north end of the inside passage, it is abundant.'

Today Glacier Bay continues to harbor a somewhat robust population of the species during the summer breeding season; a 2010 Park Service count estimated 14,500 individuals. But the global population, which is restricted to Alaska and far eastern Russia, is pegged at just 20,000-40,000 individuals by Birdlife International. Of that global population, an estimated 70 percent is thought to reside within Alaska.

Even that tally is thought to be in dizzying decline. According to the American Bird Conservancy, the overall population of Kittlitz's murrelets plunged 99 percent from 1972 to 2004. Possible causes, according to the group, range from the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Prince William Sound, Alaska, in March 1989 (as many as 500 of the birds might have died as a result of the spill, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service), to a warming climate that is altering their habitat.

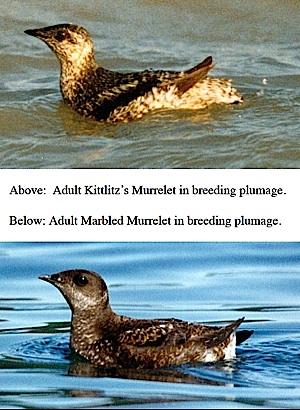

A intriguing part of the problem might have been misidentification of the Kittlitz's murrelets when counts started decades ago. The birds, covered with greyish-brown feathers that seemingly are flecked with gold across their backs, darker wings, and white tail feathers most visible at takeoff, might have been lumped together with Marbled murrelets, which are similar in coloration though a darker brown overall.

Kittlitz's and Marbled murrelets are similar in appearance. USGS photos.

Can the population plunge be reversed?

In 2001, the Fish and Wildlife Service was petitioned by a handful of conservation groups -- the Center for Biological Diversity, Eyak Preservation Council, Lynn Canal Conservation, Inc., and the Sitka Conservation Society -- to list the Kittlitz's murrelet as endangered, define critical habitat, and develop a recovery plan.

In 2004, the Service officially listed the species as a candidate for listing under the Endangered Species Act. By 2005, the Center for Biological Diversity, concerned the Service wasn't moving fast enough on the petition, filed a lawsuit to force a ruling, and to do the same on another 282 petitions for "candidate" species under consideration for ESA protection.

This past September a federal judge signed off on a settlement that calls for the Fish and Wildlife Service to determine the status of the Kittlitz's murrelet by 2013, and also defined a schedule for the agency to decide on the other candidate species' fate.

As that deadline approaches, our knowledge about this diminutive seabird with the somewhat squat body and stubby wings (which are perfect for diving and swimming underwater after prey) is changing dramatically thanks to field work that Dr. Gende and Ms. Kissling have been leading the past five summers in the waters of Glacier Bay and more northerly Icy Bay in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park.

"We're getting an understanding of the habitat where they nest and their foraging locations, and how their distributions shift around (Glacier Bay) over time," Dr. Gende says.

The work is not without peril for the researchers. To capture these ocean-going birds for banding and to attach tracking transmitters, crews head to sea in the middle of moonless nights in 15-foot Zodiac inflatables rigged with lights that can crank out 3 million candle power. Once the crew spots a murrelet, they charge straight at it and turn on the lights, freezing the birds in place like deer in your headlights, and then scoop them up in a net.

"Icy Bay, including the coastline of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, is much more open to the gulf than Glacier Bay is, and there's a lot more ice in there, too, because there are several active tidewater glaciers,' Dr. Gende says. 'So you can imagine driving around. It has to be pitch dark. If there's any light whatsoever then the birds see the boat coming and they flush and our capture success goes way down.

'Riding around out in the middle of the Gulf of Alaska in 12-foot swells, the wind blowing the tops off of them, in 15-foot Zodiacs in the middle of the night, it's crazy sometimes," he adds.

Ms. Kissling, who has been overseeing captures and banding in Icy Bay, says Marbled murrelets appear to be faring much, much better than the Kittlitz's murrelets.

'My gut feeling is that one possible reason is because Marbled murrelets can utilize a greater diversity of nesting habitats than Kittlitz's murrelets can," she says during a phone conversation from her Juneau office. "Marbled murrelets can nest in trees, on the ground, or on cliffs, and therefore their range extendsd from the Aleutians down into northern California. In contrast, Kittlitz's murrelets nest on the ground or on cliffs, which is probably why their distribution is correlated with glaciers. The natural history of both species revolves around predator avoidance, especially at nest sites, but Marbled murrelets seem to be able to take advantage of nesting habitat that Kittlitz's can't use."

Kittlitz's murrelet. USGS photo

Kittlitz's murrelet. USGS photo

Ice ages have come and gone, and the Kittlitz's murrelet has endured, raising the possibility that while their numbers are declining, they've declined before and rebounded, too.

'We have no idea how well they survived (in the wake of past ice ages), and they certainly exist in areas that have no glaciers whatsoever,' notes Ms. Kissling. 'For example the Aleutian Islands, and northern Alaska, like the Seward Peninsula near the Bering Land Bridge. They may have just hung on or adjusted their behavior during those warm periods. They nest on several Aleutian Islands, which were predator-free and offered safe nest sites, at least until rats, foxes, and other land mammals were introduced.

'But they might have gotten by just with limited nesting habitat. And so they may have always gone through these natural fluctuations,' she adds.

One disturbing fact that Dr. Gende and Ms. Kissling have identified is that Kittlitz's murrelets do not seem to be reproducing fast enough to offset mortality. Part of the reason comes naturally -- the murrelets often don't breed until they're at least 3 years old, and then they might not nest every year; they might skip one, two, or three years. Another part of the problem is predation.

'We know that, at least within the breeding season, mortality exceeds reproduction in most years. More birds are dying from, usually, peregrine falcons or bald eagles, than are reproducing young,' the Fish and Wildlife Service biologist explains.

In short, the species' reproductive process is grueling.

After a single egg is laid on the barren ground -- not even a depression is scraped out, no moss or twigs are gathered for structure or protection -- the male and female birds take turns incubating the egg in 24- or, more commonly, 48-hour shifts.

'Reproduction is costly because not only is the egg really large and heavy, about a quarter of their weight, for the female to develop and carry up to these crazy, radical, spots to lay it, but then there's a 30-day incubation period,' Ms. Kissling explains. 'So the female sits on it for 48 hours, then the male comes and they switch. So for the adults, they're fasting for up to 48 hours, and then they only have 48 hours to replenish their energy resources and fly back up and sit on the egg to do it all over again.

'So by the time incubation is over, I'm sure the adults are tired. Then there's another 25-day chick-rearing period, immediately following incubation, where whole fish are delivered to the nest,' she says. 'They don't regurgitate like other seabirds do. They deliver whole fish to the young.'

These meals -- in the form of whole herring, capelin, sand lance, salmonids, smelt -- weigh about 10 grams, and the parents might deliver as many as a dozen meals a day to their chick. The researchers know this because they were able to locate some nests near Icy Bay and set up cameras to record nest activity continuously.

The parents arrive with a fish that might equal 15 percent of the chick's weight and 80 percent of its beak-to-tail length.

"The adult will sit there and hold this fish for like 15 minutes before giving it to the chick,' says Dr. Gende, recalling the dynamics of chick rearing. 'What they're probably doing is they get that gastric acid going for the chick, and they'll hold it, and then after 15 minutes they'll finally feed it to them, and the chick will just gulk, gulk, gulk, gulk, gulk, just choke this thing down.'

When you consider where the birds nest, it's easy to appreciate the taxing schedule they maintain to nourish their chicks. Some Kittlitz's murrelet nests have been found miles from waters of Glacier Bay and Icy Bay -- in one case a nest was found at an elevation of roughly 8,000 feet on Mount St. Elias, in another it was 26 miles from the nearest saltwater.

One nest the researchers found, Dr. Gende says, 'was under this overhanging glacier, and out on the forelands of glacial till. It's the most amazing thing you'd ever see. You look at this thing and it's a rocky, icy, rocks, snow, mountain landscape. And you're thinking 'what the heck are these birds doing up here.'

'Lo and behold, you go up there and there's a little tiny murrelet ... there's no nest structure, it's basically underneath a rock or something like that that they just sit down and pop out an egg.'

A Kittlitz's murrelet fitted with a transmitter. Photo by Michelle Kissling, USFWS.

Against this demanding reproductive cycle, climate change could be adding another challenge by altering the murrelets' habitat -- replacing icy slopes of glacial moraine with vegetation that creates habitat for predators such as bald eagles and peregrine falcons.

'My personal feeling is that a lot of what's happening with Kittlitz's is actually happening in the terrestrial environment," says Ms. Kissling. "As glaciers thin and recede and vegetation succession moves forward, replacing inhospitable, icy, rocky terrain with green, vegetated habitat that can attract and support many wildlife species, I think this transition has provided a lot of opportunities for a new suite of species. We tend to think of green, vegetated travel corridors as good things for wildlife, but I think that Kittlitz's prefer the harsh, barren -- and predator free -- glacial terrain.

'If you nest on the ground and only lay one egg every few years, your whole point is to be remote and away from everything else. ... In a study of murrelets on Kodiak Island, which used to be heavily glaciated but now is not, the most common reason for nest failure of Kittlitz's is fox predation.'

Another part of Dr. Gende's and Ms. Kissling's research is to determine whether human visitors to Glacier Bay National Park are detrimentally stressing the seabirds. That data could impact visitors if the species is listed as endangered or threatened and critical habitat is carved out of the park.

Studies (see attached below) have shown that prime foraging areas for the murrelets -- waters close to tidewater glaciers -- are often destinations for cruise ships so passenges can marvel at glaciers close-up. Data collected so far in their research demonstrate that ships do flush birds from the water, but what the impacts are of those disturbance events to birds' health or reproductive success is uncertain.

'Breeding Kittlitz's murrelets are highly sensitive to vessel activity, and susceptible to fitness effects from incurred energetic costs and potential loss of their held fish,' Alison Agness wrote in a paper that appeared in Alaska Park Science, Volume 9, Issue 2, this past August. 'The park could consider area restrictions to minimize vessel traffic during the season when Kittlitz's murrelets rear their chicks (~June 21-July 15 in Glacier Bay), particularly in known Kittlitz's murrelet 'hot spots' in the bay. Speed restrictions in these areas (<10 mi/hr) may help minimize dive responses, but would not alleviate flight responses, and both types of disturbance carry potential fitness consequences for breeding birds.'

A similar concern is that research on Marbled murrelets in Auke Bay near Juneau has shown that when the adults are disturbed while fishing for their chicks, they'll 'actually eat the fish as opposed to take it up to the nest,' says Dr. Gende. If that holds true with Kittlitz's murrelets, it could lead to lower reproductive success because the parents would be eating meals intended for their young and expending more effort to forage to replace those gobbled meals.

A Kittlitz's murrelet fishing during breeding season. NPS photo.

Glacier Bay already has restrictions in place as to how close cruise ships, tour boats, and even kayakers can get to wildlife, but wildlife sometimes invade those distances, forcing boaters to back off.

Paddling back from Marjorie Glacier, with birds winging overhead to inspect us, our focus was on dodging the icebergs bobbing around us. A warming climate is changing this place. As recently as 1907, the waters we're navigating were glacial ice; in 1892, all of Tarr Inlet was part of the Grand Pacific Glacier.

Now it is open water, which is good for humans hoping to gaze upon glaciers, but perhaps not the best for the birds. Against the cacophony of bird calls sweeping down from the cliffs, that was a sobering thought.