In the spring of 1948, Pennsylvania native Earl Shaffer stumbled into Stecoah Gap on the Appalachian Trail, high above the Little Tennessee River in western North Carolina’s Graham County. “I must have been a pathetic figure,” he wrote later in his memoirs, “streaming with sweat, bleeding from scratches, every muscle aching, crawling endlessly in a back-slipping, bush-clutching struggle before coming out on top.”

The gap was a turning point for Shaffer, a war-weary veteran turned hiker who would become the world’s first person to complete a continuous thru-hike of the Appalachian Trail later that year atop Mt. Katahdin, Maine. By the time he hiked through the gap, Shaffer had endured several weeks of off-and-on rainstorms and some of the Trail’s most rugged terrain. Climbing the hill on the other side of the gap, Shaffer would head towards the Great Smoky Mountains, a region he would later remember as “four straight days of sunnytime and moonlit nights, a halcyon interlude…Nowhere else on the Appalachian Trail do I feel so strong an urge to return.”

More than six decades later, Stecoah Gap, perched near 3,200 feet above sea level and a short drive north of Robbinsville, North Carolina, holds a similar symbolism for hikers traveling America’s first National Scenic Trail. For those headed northbound, Stecoah Gap heralds the approach to the Great Smoky Mountains, much as it did for Shaffer years ago. For southbound hikers, the gap signals the beginning of the trail’s stretch through the infamous and beautiful Nantahala Mountains, arguably some of the A.T.'s most rugged terrain. Although bisected by a scenic stretch of two-lane state highway, Stecoah Gap is, above everything, a steadfast landmark that has persisted mostly untouched on the Appalachian Trail since the end of World War II.

This serenity, however, might be about to change. In June of 2008, officials with the North Carolina Department of Transportation released a Draft Environmental Impact Statement stating their intent to construct a new highway through Stecoah Gap and across the Appalachian Trail. The project is part of a larger proposed highway stretching from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Asheville, North Carolina, and deemed “Corridor K,” one of 30 such corridors originally identified by the Appalachian Regional Commission in 1964 as future highway projects in the Appalachian region.

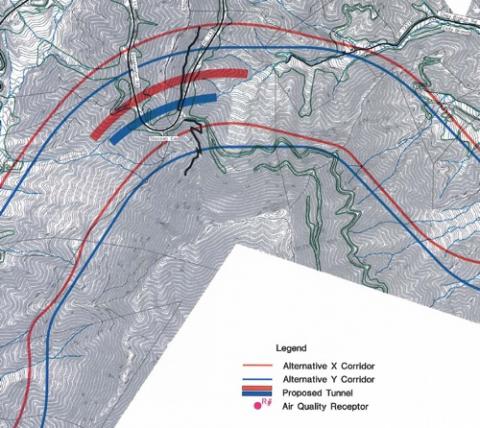

As currently proposed, Corridor K is slated to cross the A.T. at Stecoah Gap via a four-lane roadway drilled beneath the mountain in a 2,870-foot long, 570-foot deep tunnel. A secondary alternative places a slightly shorter and shallower tunnel through the gap. While not directly removing any part of the footpath itself, construction of the roadway would remove a wide swath of pristine forest that is currently visible from overlooks further up the trail, forever altering the trail’s scenic character. Furthermore, scars from rock excavation necessary for the roadway would be visible from trailside overlooks on either side of Stecoah Gap." (Ed: This graf was updated to reflect decision not to pursue a road cut but rather concentrate on a tunnel.)

Not surprisingly, the road proposal has both local residents and the larger trail community up in arms. Proponents of the project argue that constructing a new roadway through the trail corridor would improve safety for drivers and spur economic growth. An economic study conducted in 2007 concluded that Corridor K was necessary to “support an economic future we will be proud of.” This study, however, never directly addressed any components of the National Park System expected to be impacted by Corridor K.

Opponents of the road include local residents and the Appalachian Trail Conservancy itself – the group charged with the management and maintenance of the trail corridor. In a comment filed with the North Carolina Department of Transportation in late 2008, the conservancy stated, “The proposed US 74 Relocation (Corridor K) will have significant negative impacts on the A.T. and its users…There will be significant changes in the viewshed as seen from the A.T., for example from the overlooks on Cheoah Bald and the rock outcrops along the A.T. north of Stecoah Gap, which will greatly diminish the primitive experience the A.T. is intended to provide.”

Up to 50 other regional and national organizations have echoed this opposition of Corridor K by way of WaysSouth, a group formed to promote responsible transportation projects in the Appalachian region. One of these groups, the Southern Environmental Law Center, has echoed the conservancy in a release about the Corridor K project:

“First proposed by the Appalachian Regional Commission in the 1960s, Corridor K was then seen as an economic boon for the area south of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Today, however, it’s clear that the remaining segments of this project would jeopardize the region’s true economic engine: the unspoiled vistas, clear-running trout waters, and backcountry recreation sites that drive outdoor tourism.”

Outside of these environmental and economic impacts, however, the Corridor K proposal raises some deeper questions about the intrinsic nature of our national parks. The Appalachian Trail is one of the nation’s most unique parks, stretching in a continuous 2,175-mile swath of protected land across the highlands of the Eastern U.S. that rarely measures more than a mile in width. This linear nature inevitably places the A.T. at risk of conflicts with development and society, and the Corridor K proposal is certainly no exception. On one side of the debate are the concerns of local developers and governments, who see the new roadway as a boon for local economies. On the opposite side is the National Scenic Trail itself, which was originally developed under the purposes of promoting “the preservation of, public access to, travel within, and enjoyment and appreciation of the open-air, outdoor areas and historic resources of the Nation.”

In between these two sides are questions that desperately need asking – and answers. Does protecting the natural, cultural, and even personal heritage embodied by locations on the trail involve rejecting road proposals that might forever alter – or even eradicate – those very places? Can the existing roadway through Stecoah Gap be improved so as to fit the goals of both regional planners and the national scenic trail, instead of a project that fits the goals of only one set of stakeholders? Does a place as unassuming as Stecoah Gap, North Carolina, even deserve protection? No matter how clear-cut the answers might seem, these are all questions that should be a major part of the discussion surrounding a project planned to impact one of the most storied components of the National Park System, but to date, they remain largely absent from the dialogue.

Although he passed away long before Corridor K became a controversial issue with the Appalachian Trail, it isn’t too difficult to see where Earl Shaffer might stand. In 1965, Shaffer became another part of A.T. history when he completed a second, southbound thru-hike, becoming the first person to travel the length of the National Scenic Trail in both directions. On a Tuesday in October, he passed through Stecoah Gap once more, spending the night under a rock shelf just off the highway. During the course of this thru-hike, Shaffer jotted down a poem in his trail journal, writing “The poisoning of water,/air, and soil/Is reaching limits where/man can survive. Yet man is blind and/greedy, bent on spoil/And soon there may/be few men left alive.”

Forty-five years later, those few lines of verse still ring true as a poignant reminder, regardless of your personal outlook on Corridor K. When it comes to projects like this one, it only hurts us all by leaving our national parks out of the discussion.

Comments

The local TN Sierra Club also is completely against Corridor K. It would lead to destruction of one of the universes most biodiverse areas and little more. The runoff from this road would poison the Ocoee River that is internationally famous for white water. The Cherokee Forrest is home away from home to me and many other weary city dwellers. The forest allows us relief from the man-made world and brings us back to the beauty of creation. The economy of this area depends on eco-tourism. Destruction of our natural resources would deplete the area of it's true wealth. - Elizabeth Tallman-Gazaway, Chair Cherokee Group Sierra Club

My wife and I also very much oppose Corridor K and the newly proposed I-3. Why do people insist on easy access to every square inch of earth with a hi-speed interstate going through every spot? Some places should be left alone and are better because they are hard to reach. I urge everyone to learn about these issues and fight it. It cannot be undone. Once the roads are built, the areas are no longer serene and wild.

There are only two options under consideration, and both of them involve a tunnel beneath Stecoah Gap. The rock-cut options have been dropped, thank God. Not that I want a road at all, don't get me wrong. But the tunnel would definately be the lesser of two evils.

Thanks for the update on the rock-cut option, Tom. I was still of the understanding that it was on the table due to some comments from the NCDOT about it that were made last year. I'll make sure the piece gets edited to reflect those changes.

While I am a camping and hiking enthusiast (as most people visiting this site probably are) I think the timing of this article is interesting. In November 2009 a rock slide closed US highway 64 Through the Ocoee River Gorge (interesting video at http://www.timesfreepress.com/news/2009/nov/11/rock-slide-shuts-down-us-... ). Estimated completion of reopening the road is now the end of March 2010. Emergency services have been severely hampered and people have died due to having to use a lengthy detour to get to hospitals. I am not saying that the entire Proposed route is essential but people who are isolated in these areas are demanding that an alternative route be provided before another slide occurs. This is a case where an article is only telling one side of a story.

Alan,

The section of Corridor K that you are talking about is a different one than the one mentioned by the author. As I understand, there are about 3 different sections of the road, each being planned independently and managed by different groups. The one you refer to is in Tennessee and is located in the Ocoee Gorge. The Tennessee DOT is heading up the planning of this project and overseeing it. It's a bit more controversial with the public.

The section the author mentions is being planned and managed by the NCDOT over 50 miles away in North Carolina. The local residents surrounding this particular section are very much against any road construction and don't see the need for this section's completion, as was shown at recent public comment meetings when only one or two people voiced approval while literally everyone else was completely opposed.

So, in essence, this article isn't presenting one side of the story. It's just focusing on a different section than you're concerned with. Your section doesn't directly impact any national parks, so it's essentially off-topic from this story. Not that it doesn't matter, but you're trying to compare apples and oranges.