At Mission San Juan, Superintendent Christine Jacobs and Ranger Destiny Gardea stand at the sluice gates of an ancient acequia that is used to water fields farmed by the San Antonio Food Bank/Jennifer Bain

With a pleasing whoosh, the water from the acequia was released through a sluice gate at Mission San Juan in San Antonio and trickled through a hand-dug irrigation ditch towards a demonstration field teeming with corn, peppers and squash.

I stood in the Texas heat with the National Park Service and San Antonio Food Bank for a few quiet moments, finally understanding how this simple but ingenious method of watering crops has nourished people here for more than 300 years.

But first I had to learn to say ah-se-kyahs — a Spanish word derived from Arabic that means irrigation ditch. Acequias are community-operated ditches brought to Spain by the Moors, and then brought to the Americas by the Spanish.

Acequias were the lifeblood of the missions, the umbilical cord if you will that connected the landscape with the people and growing communities in the 1700s. Today these same acequias still deliver water rights and help people grow food.

In the demonstration field at Mission San Juan, the San Antonio Food Bank's Liliana Reyes farms and chats with National Park Service Ranger Destiny Gardea/Jennifer Bain

In the only partnership of its kind, the food bank farms five acres of National Park Service land as a historic demonstration garden to educate visitors to San Antonio Missions National Historical Park. It manages another 45 park acres, using modern farming methods to cultivate crops that will feed the hungry.

“I’m glad you’re telling the story because it’s under-told and underappreciated,” Michael G. Guerra, the food bank’s chief resource officer, said to me. “For those that see and experience it, they’re hooked. They go `wow’ and they’re in, like it’s the greatest thing in the world.”

That’s a good description for how Christine Jacobs feels about acequias. Part of her job as San Antonio Missions superintendent is to manage about 13.5 miles of wet (flowing) acequias, and an equal amount of dry acequias, all in the seventh largest city in the United States. “The San Juan Ditch is more than just an irrigation ditch — rich history has international significance," said Jacobs. "It has been in place from the Spanish colonial period and is still essential to delivering water rights today."

The question, then, is how to convey how significant these ditches were and still are.

The farm fields are just behind this part of the acequia at Mission San Juan/Jennifer Bain

This is a city that literally revolves around water.

In town for a travel conference, I spent five days strolling below street level between the Hyatt Regency San Antonio Riverwalk near the Alamo Plaza and the Henry B. González Convention Center (named for a Democratic Mexican-American congressman) along the San Antonio River Walk.

Sometimes called “the American Venice,” the 15-mile River Walk is one of the most visited places in Texas. The downtown stretch is flanked by restaurants, shops, hotels, apartments and a public art garden. River barges are full of tourists taking guided tours. One night we were treated to a river parade and on another it was a private party at La Villita, an artisan and entrepreneur village on the river's south shore that's listed on the National Register of Historic Places for architectural styles that range from adobe structures and early Victorian to Texas vernacular limestone buildings.

The downtown stretch of the San Antonio River Walk is marked by restaurants and boat tours/Jennifer Bain

I learned how local Indigenous people first called the San Antonio River “Yanaguana” meaning “refreshing waters.”

Interpretive signage detailed how Spain ruled Mexico for 300 years ending in 1821, basically ignoring its northeastern frontier until French settlers built outposts near the Red River in Louisiana. That prompted the Spanish to establish missions in East Texas in the 1690s to convert the Indigenous people to Christianity and make them loyal to Spain. A way station was built at today’s San Antonio in 1718. This outpost had a presidio (military barracks) and the Mission San Antonio de Valero, which is now the state-run Alamo.

Mission San José was founded down-river in 1720 and Mission Concepción, Mission San Juan and Mission Espada followed. All the missions became parish churches in the 1790s. Mission San Antonio de Valero, the site of a famous battle for Texas independence in 1836, is now a museum and shrine. The four down-river mission churches remain active parishes — another partnership that the park service navigates while maintaining appropriate boundaries between church and state.

Mission San José is home to the national historical park's visitor center and this iconic (and still active) church/Jennifer Bain

Most tourists will find their way to San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, which was established in 1978 and hosted almost 1.3 million visitors in 2022. Many are drawn by the fact that most of the missions — along with the Alamo and a ranch south of the city — form the only UNESCO World Heritage Site in Texas. The missions are considered an example of the interweaving of Spanish and Coahuiltecan and other Indigenous cultures that are a vital part of America’s heritage. The acequias are specifically identified in the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the inscription.

“All cities, probably around the world, that were populated early were populated because of water," Guerra pointed out. "People gathered around water sources and springs, and San Antonio is no different, or course. But with industrialization now you just happen to be a city around water, and you’re like `oh that’s fun for recreation and other things.”

The beauty of the acequia system, he continued, is that you still see it in action.

“You might have the river and people running up and down the river and they’re jogging and they’re taking their dogs and they’re biking and it’s cool and you can kayak and it’s water and it’s what it is. But this, I think, really reminds you that people settled here and they had to have water and they had to have water access and live along the river — what an incredible diversion plan. And so educationally and culturally, what an opportunity to touch all these topics from justice to conservation to climate to crops.”

Michael G. Guerra, chief resource officer with the San Antonio Food Bank, stands over an acequia near the fields the food bank farms for food and for demonstration purposes/Jennifer Bain

The mission’s founders planned the acequia system so that water flowed by gravity from a dam through a sluice gate to the fields. Water traveled through the larger acequia madre (mother ditch) to the smaller upper and middle ditches to distribution ditches along the fields. Each mission had its own dam and network of acequias.

The Indigenous people were tasking with digging the ditches, and the well-watered fields produced several abundant harvests a year. The once self-sustaining missions also raised animals and when they had surplus crops, sold or traded them. After the mission period, a mayordomo (ditch master) allocated shares of water called dulas to each farmer on specified days.

It is often said that San Antonio wouldn’t be San Antonio without the missions. In the same breath it should also be said that the missions wouldn’t have survived without the acequia system. They run as a closed system that diverts water from the river that irrigates fields, delivers water rights, supports the cultivation of crops and then feeds back into the river. The acequias maintain a slow flow, descending at about 17 inches per mile.

“The San Antonio Ditch is also, in my opinion, one of the most vulnerable resources because people don’t notice it,” said Jacobs. “(It weaves) through backyards and seems to just go off in the distance but it is a closed system conencted to the San Antonio River.”

Just outside Mission Espada, you can see the acequia as you drive by/Jennifer Bain

The park service employs Spanish colonial masons devoted to maintaining the acequias. They also partner with everyone from the Texas Conservation Corp., City of San Antonio, San Antonio River Authority and Archdiocese of San Antonio to the county and Mission Descendant community in this highly complex unit. The San Juan Ditch Water Supply Corp. is a non-profit corporation established in 1967 to own and operate the ditch, which delivers the oldest water right in the state of Texas. The NPS and the San Antonio River Authority hold the majority of the water rights in the ditch.

On April 5, the park service hosted a gathering of about 40 descendants of people who built the missions to chat about the education, preservation and protection of the mission sites. Mission descendants come from a diverse group of Texans with Indigenous, Latino and European heritage and whose ancestors lived on the mission lands before, during and after the mission period. They make the missions a living community and gather at the missions for important life events like baptisms, confirmations, marriages, Indigenous celebrations and prayer. On Apr. 29, Mission San José hosted its annual History & Genealogy Day where mission descendants bring photo albums, swap stories and forge new ties.

As we stood at the Mission San Juan acequia that feeds the demonstration farm, a birthday balloon and plastic water bottle floated by and were quickly retrieved, reminders of modern urban challenges. I learned that heavy rains and a power outage had recently caused the nearby San Antonio Refinery’s water treatment plant to spill an estimated 9 to 12 gallons of oily water into the acequia. Park staff saw an oil sheen on water and oil on the plants on the acequia's bank.

But that spill was swiftly cleaned up and the crops were thriving when I visited. “Right here we have potatoes. We have popcorn. We have got squash in between these two layers of corn,” explained Ranger Destiny Gardea. “I believe over there they have more ornamental plants.”

Liliana Reyes, a farm and garden worker with the San Antonio Food Bank, stands in the demonstration field at Mission San Juan/Jennifer Bain

Liliana Reyes, a farm and garden worker with the food bank, held up cardinal basil and lime basil, and pointed out amaranth and cilantro. We chatted above the noise of a tractor and the roar of planes coming and going from Stinson-Mission Municipal Airport.

It has been seven years since the food bank and the National Park Service partnered. At the time, the food bank made news for farming 25 acres at its main facility just as the park was looking for a way to bring the fallow fields back to life. Now, using modern farming methods, the food bank grows about 100,000 pounds of produce a year, depending on the crops.

“Watermelons weigh a lot, peaches don’t, so I would say it’s just the starting point,” acknowledged Guerra. “We have more fields still to develop. I think we feel that could go up to half a million pounds easily in the coming years.”

Tucked behind this "Lifeblood of the Missions" interpretive sign at Mission San Juan is an acequia and active farm fields/Jennifer Bain

Gone are the days when food banks only handed out shelf-stable items. Two-thirds of what the San Antonio Food Bank distributes now is fresh or frozen. The farm bounty — potatoes, sweet potatoes, watermelon, corn and cabbage — goes to low-income people facing hunger who usually choose staples at the grocery store instead of vegetables and fruits.

Guerra said the ability to grow fresh food, teach about it and then share it “is beautiful because it’s the skipped item in the grocery store.” He spoke about one woman who was thrilled to finally introduce her 4-year-old son to watermelon, an item that was too heavy for her to buy since she takes the bus to the grocery store.

As we watched the acequia water trickle towards the field, I learned that the water doesn’t constantly flow. With flood irrigation, you open a sluice gate to allow water to go into the rows and soak in, but then you close the system off again until needed, and give your neigbors a chance to access their fair share.

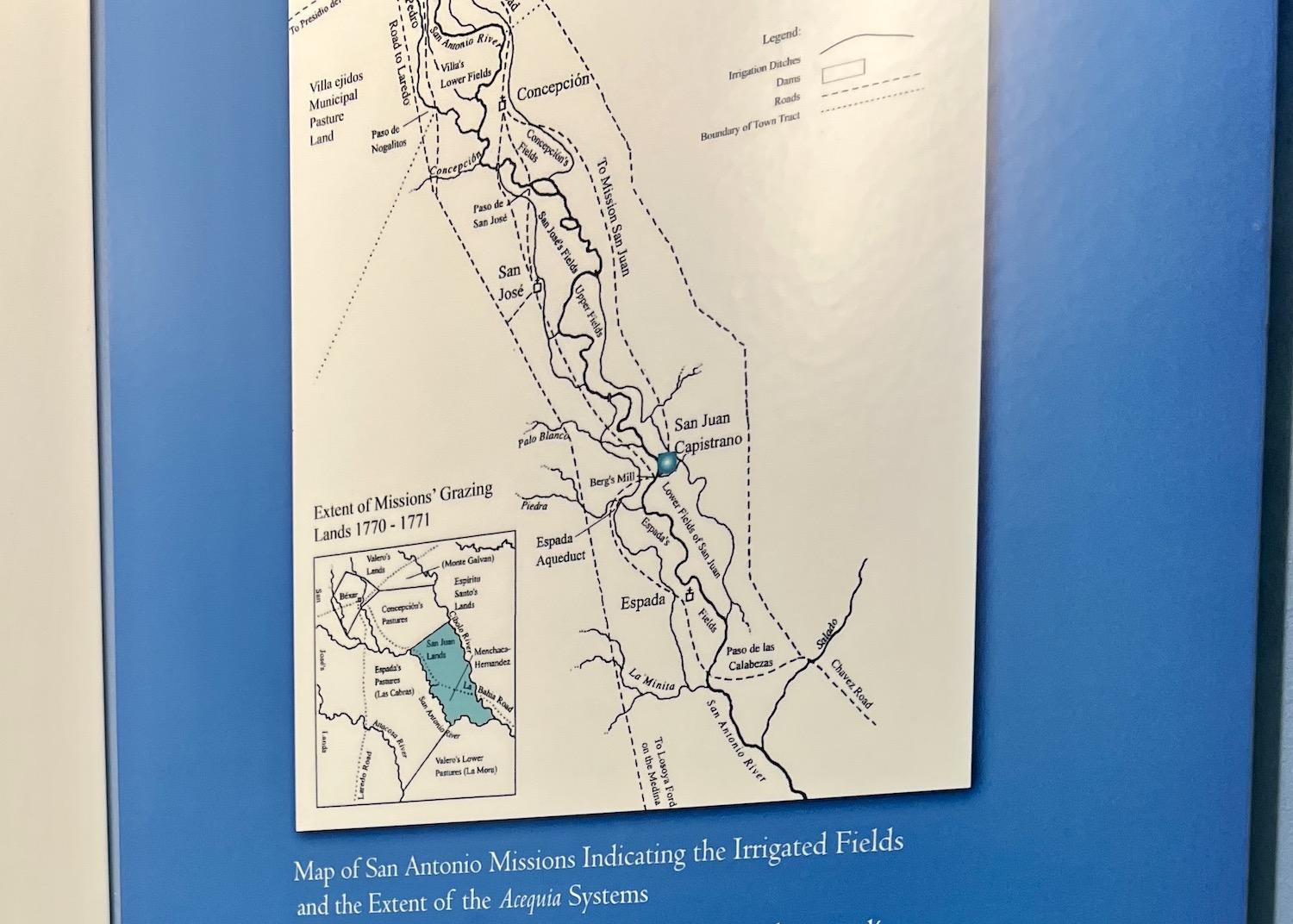

A map helps you visualize the extent of the acequia system that connects the missions/Jennifer Bain

“Typically, just to fill that small farm field, it usually takes 45 minutes to fill the whole thing,” explained Gardea. “Lili (Reyes) was just telling me that yesterday because of the last few weeks of rain and everything that they had, it took 10 minutes.”

The park offers ranger-led acequia hikes and hosts school groups, who get a kick out of lifting the sluice gates, hearing the whoosh and seeing a big gush. It’s a hands-on way to teach kids about the historic and ongoing need to access and share water.

“The land and the water are still nourishing neighbors within San Antonio — those low-income neighbors that aren’t able to set the table for themselves,” said Guerra. “This demonstration section is more educational and cultural. And then the remainder parts, really, we’re able to get as high yield as possible to help feed the community and set the table.”

Near Mission Espada, the acequia system is visible behind homes/Jennifer Bain

There are 200 regional food banks in the U.S. Only three to five per cent have farms, but Guerra said those are usually urban plots that are more like community gardens. San Antonio is the only food bank that has partnered with the National Park Service.

A first-time visitor to this mission might not even realize the farm exists, since it’s tucked away behind the main courtyard. But new wayside panels are coming and the farm fields will also be included on a new orientation board.

After touring Mission San Juan’s fields, I visited Mission Espada to see how the acequia quietly runs behind people's homes. I also stopped in at the Espada Aqueduct, which is a National Historic Landmark.

The Espada Aqueduct is a National Historic Landmark that goes over a creek and was recently drained to clear sediment/Jennifer Bain

Most acequias were hand-dug, earthen ditches that maneuvered the terrain but some had to be built over creeks and other barriers.

Built between 1740 and 1745, the Espada Aqueduct is the oldest Spanish aqueduct in the United States. It carries water over Sixmile Creek (historically Piedras Creek) connecting the ditches. It spans the creek with two arches and one support pier and has withstood major floods and nearly 280 years of wear and tear.

The park service and its partners just wrapped up preservation, maintenance and repair work on sections of this stone aqueduct thanks to $290,000 in funding from the Great American Outdoors Act.

San Antonio Missions Superintendent Christine Jacobs stands at the Espada Aqueduct/Jennifer Bain

The team drained the aqueduct using a diversion gate and an open sluice to clear a heavy load of sediment from the masonry portion of the channel. Mud and soil was removed by hand, and the masonry channel was thoroughly cleaned. The plaster surface was assessed to locate small cracks and weak mortar joints. Deteriorated plasters and mortars were removed and preservation treatments were done both inside the channel and on the exterior masonry before water was finally reintroduced.

In a perfect world, this important work would be done every 18 months.

San Antonio Missions Superintendent Christine Jacobs and Ranger Destiny Gardea stand over an acequia at the Espada Aqueduct/Jennifer Bain

Acequias, I learned, are both durable and fragile. They need to be constantly monitored in case heavy rains cause catastrophic blowouts. Managing them is a lot like managing a trail where the work is never done.

My water-themed explorations ended at Mission San José, the “Queen of the Missions” and home to the park’s visitor center, a granary and the oldest grist mill in Texas. Built around 1794, the mill was part of the effort to add wheat to the traditional maize-based Indigenous diet and it also produced flour for surrounding settlements.

“By means of acequias or ditches, this mill, the oldest in Texas, was run by water from the San Antonio River,” a plaque reveals. “The lower part of the mill is original. The upper room is restored. After powering the mill, the water was conducted through the lower ditch to irrigate the fields.” The acequia still flows but it's no longer connected to the river. Instead it's on a closed pump system and is always ready to showcase to visitors.

Behind the iconic church at Mission San José is the oldest grist mill in Texas and an acequia that's now on a closed-pump system so people can see how it works/Jennifer Bain

In chatting with park staff, I discovered one final, fascinating fact about this complex place — the Missions have a land and water acknowledgement.

These statements usually recognize the traditional territories of the Indigenous people or peoples who called a place home before European settlers arrived. This one goes further to acknowledge the San Antonio River as Yanaguana ("Spirit Waters" in Payaya), and it honors the unbroken ties between Indigenous peoples and their traditional lands and waterways at "this special place."

The acequia that powers the grist mill at Mission San José is now on a closed-pump system and so has a stable water level/Jennifer Bain