Global Conservation works in national parks and World Heritage Sites, such as Mana Pools World Heritage Site in Zimbabwe, to protect biodiversity/Global Conservation

Defending National Parks Globally

By Lori Sonken

"Ecocide" in Venezuela's national parks, elephant and rhino poaching in African parks, wildlife trafficking in Vietnam's parks, and illegal gold mining in Belize's parks are just some of the blights on the global collection of national parks and protected areas. It's an ugly list of threats to biodiversity that keeps Global Conservation busy.

The eight-year-old nonprofit organization funds efforts to stop illegal wildlife killing and logging in parks and marine protected areas worldwide, and is already seeing results, including no elephant killings three years in a row in Mana Pools World Heritage Site in Zimbabwe, said Jeff Morgan, executive director.

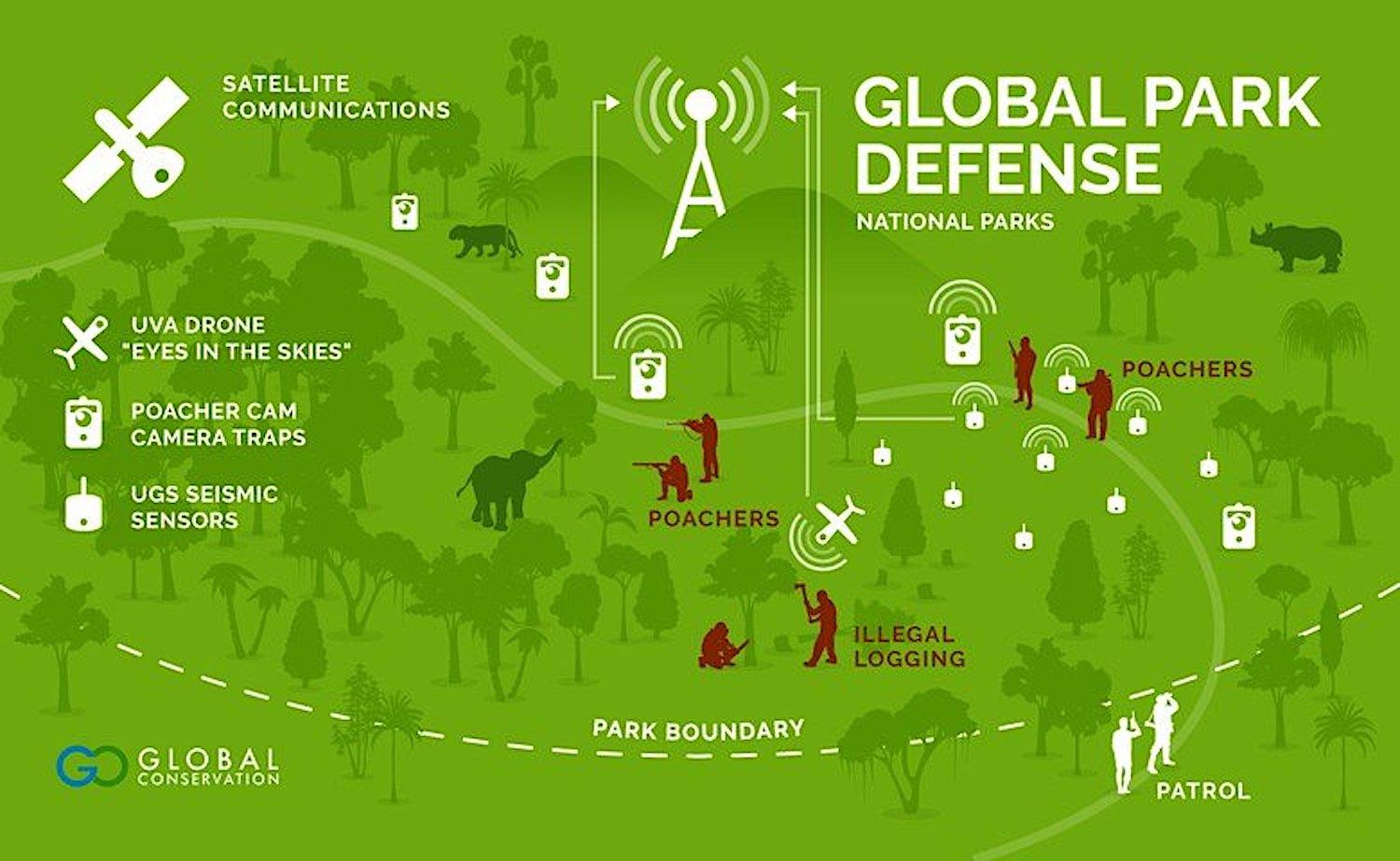

Operating in UNESCO World Heritage Sites and national parks with high tourism potential, Global Conservation steps in when reasonably certain that local managers are willing to commit resources to defend the area’s flora and fauna against criminal syndicates. Tailored to each park’s needs, the organization’s formula for success —costing about $100,000-$120,000 annually per park for five years— includes deploying satellite cameras to survey resources and detect illegal harvests, as well as human patrols to monitor parks and arrest violators.

The organization partners with conservation organizations to support activities. In Guatemala, for example, Global Conservation works with FUNDAECO and Rain Forest Trust to protect the biologically and culturally rich forest in northern Guatemala and southern Mexico. The groups formed the Mirador Park Authority to patrol 1.6 million acres proposed to be included in Mirador National Park. Home to jaguars, pumas, tapirs, and ocelots, the proposed park also contains more than 40 ancient Mayan cities and the gigantic La Danta pyramid soaring 230 feet into the air and resting on a base reportedly the size of 35 football fields. But looting, cattle ranching, logging, poaching, and drug trafficking threaten the resources.

At Mirador stands the most voluminous pyramid in the world, called La Danta, that the Maya built/Global Conservation

A team of six rangers formed Genesys, with support from Global Conservation, to stop illegal logging, road construction, and hunting, said Francisco Asturias, director of the conservation organization, FUNDAECO, in Peten. They are preventing criminals from illegally cutting granadillo, a wood used in luxury cars, jets, and stringed instruments.

“We have the best managed park in all of Central America. We also have the best rangers and park guards in Central America,” he said.

Asturias appreciates the funding received — about $586,000 from 2016-2019 — from Global Conservation. The monies provided the rangers with uniforms, radio communications technology, all-terrain vehicles, and camping equipment. Since 2019, Genesys has played a role in sending 13 people to jail, Asturias said.

“This is a never-ending job,” he added. There is no time for vacations or holidays. When the rangers step away, the looters step in.

In Asturias' view, corruption is what keeps governments from supporting national parks in Central America.

“Most parks in Latin America are paper parks,” he said. By this, he means they have a park name but are abandoned by governments influenced by cartels. The parks have little to no funding or staff.

"Paper parks" is a term Morgan also uses to describe parks counted in the international 30x30 effort announced in December at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference, known as COP 15. About 190 countries, excluding the United States, signed an agreement to protect 30 percent of the planet’s land and oceans by 2030. Though the U.S. Senate has not ratified the U.N. agreement, President Biden issued Executive Order 14008 shortly after taking office in January 2021. The EO encourages the secretaries of the Departments of the Interior and Commerce to solicit information from states, tribes, and others to identify strategies to conserve 30 percent of U.S. lands and waters by 2030.

A number of strategies are employed to protect natural resources around the world/Global Conservation

“30x30 is doing a disservice to conservation and protection,” Morgan said, noting that many lands are called parks, but they do not have the legal protections most parks within the U.S. National Park System have, including no hunting or oil drilling (except in preserves) or logging and no new claims for mining, and grazing once the park is authorized.

Countries contend their lands and waters count towards meeting the 30x30 goals — as Colombia’s former President Ivan Duque Márquez did — but Morgan said this claim is fake.

“The ocean is not protected in Colombia,” Morgan said.

Similarly, Palau’s President Surangel Whipps, Jr. joined the 30x30 effort, but struggles to protect biodiversity. Home to coral reefs, sandy beaches, seagrass beds, mangroves and atoll forests, Palau, is an archipelago in the western Pacific often described as a paradise, but the country suffers from overfishing.

“How are they going to protect anything if they don’t have a boat running? The locals have good fishing boats. They are taking all the fish,” Morgan said.

Global Conservation assists Palau by providing marine radar and thermal long-range cameras to detect illegal ocean activities.

In Cameroon, Global Conservation is working with local government agencies and communities to boost populations of the western lowland gorilla, the African elephant, and the chimpanzee in the Dja Faunal Reserve conservation complex, an area the size of Lebanon that reportedly gets little support from the Cameroonian government

“Global Conservation in collaboration with the Cameroonian government and other conservation nongovernmental organizations is putting in place its global defense approach to combat illegal poaching, pursuing effective prosecution of wildlife crime and integrating other stakeholders such as local communities and the private sector into conservation,” said Oliver Fankem, Central Africa director for Global Conservation, in an email.

Morgan’s group also works to protect the surviving Sumatran rhino and Komodo dragon in Indonesia. In Uganda, Global Conservation deployed radio communications across most of Murchison Falls National Park, built four ranger stations and completed the construction of a command center, armory, and jail.

Tax filings show Global Conservation’s revenues in 2020 were $3.3 million, while expenses totaled $1.8 million, including Morgan’s $96,000 annual salary.

“We spend a lot of money on equipment and kits, but not guns,” he said.

Rescued African gray parrots at Dja Faunal Reserve waiting for a medical check before quarantine.

The work can be dangerous. At Otishi National Park, also in Peru, cartels are said to have paid locals to cut and burn down the forests. Seven policemen opposed to people growing coca within park boundaries were reportedly slain. Efforts are also underway in Peru to combat coca trafficking and illegal logging in the Sierra del Divisor within the Amazon.

In Belize, Jon Ramnarace, hired as director of marine protection for Turneffe Atoll Sustainability Association, was murdered, along with his brother late last year. A recent Global Conversation hire, he previously worked for the Wildlife Conservation Society where he developed a national training program for rangers to use software, as well as aerial and underwater drones for surveillance to conserve marine and land resources.

“Unfortunately, greed and criminals took his life right when he was taking a leading role at TASA,” said Morgan.

While parks in the United States are supported by police, including NPS law enforcement officers as well as local police and the FBI, parks abroad often are not. Morgan believes the NPS needs to step in and lend a helping hand.

“We are always talking about conserving our planet. These countries have the forest. We are not giving them anything to protect themselves. We (Global Conservation) are providing what the U.S. government should provide — staff, transportation and improved protective management,” he said.

“Major untapped potential” at the National Park Service could provide the foreign assistance currently lacking — almost no foreign aid spending helps developing countries in sustainable community development and national park protection, said Morgan.

He believes the Park Service's efforts abroad could effectively provide jobs, keep parklands and forests intact, conserve endangered species, and sequester carbon critical to addressing climate change.

“We should take our model – the gold standard – and replicate it around the world to save the planet,” Morgan said.

In response, the Park Service said in an email that it would not comment on a specific organization’s proposal. But Maria Cavins, a public affairs specialist with the Park Service, said the agency “cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world.”

The Park Service’s Office of International Affairs has a staff of six and a $1.2 million annual budget. The office works internationally — usually at the request of and funded by countries, organizations, and other federal agencies. The agency has “influenced the development of park systems in nearly every country in the world,” according to Fiscal Year 2023 Budget Justifications.