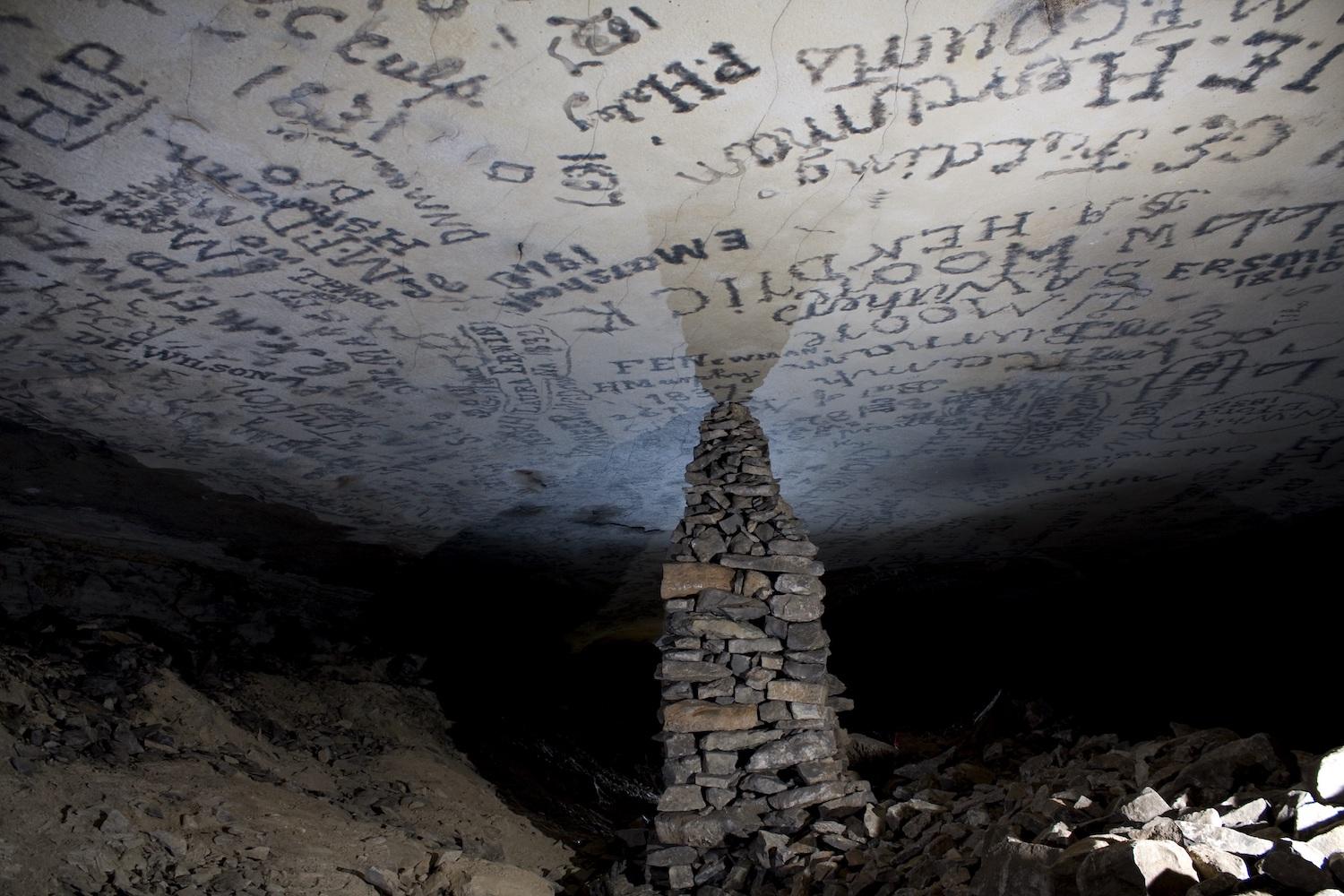

Somewhere among the many names on the roof of Gothic Avenue is "Mat 1863"/NPS

A Mammoth Family Story

By Kim Kobersmith

Mammoth Cave guide Jerry Bransford has a favorite moment during his cave tours. It is while the group passes through Gothic Avenue, a chamber of historic graffiti written by guides and tourists on the cave walls with smoke, or soot. He points out one inscription in particular that simply says, “Mat 1863.” Then he begins to tell the story of Mateson Bransford — one of the first guides in the cave and his great-great-grandfather.

“I am privileged to see my ancestors’ names on the walls, and that means a lot to me,” said Jerry. His kinfolk have had an intimate relationship with Mammoth Cave and a profound impact on its visitors for five generations. As guides, they introduced countless people to the cavern’s wonders. As explorers, they helped develop cave tour routes that echo today.

Fifth-generation Mammoth Cave guide Jerry Bransford is on a mission to preserve his family history in the park/NPS

The cave has long been part of Jerry’s life as well. When he was growing up his father, David, brought the family to visit the park regularly. They would wander on Flint Ridge, home to generations of their family before Mammoth Cave became a national park, and told him that the Bransfords were important here.

Yet the full and complex family story, encompassing love, labor, and pain, was almost lost to history. It wasn’t until Jerry became an adult, asking questions about some pictures he inherited from his great-uncle, that he began to piece that mosaic together. At the same time, Joy Lyons, chief program officer at Mammoth Cave National Park, was sifting through old pictures and asking similar questions.

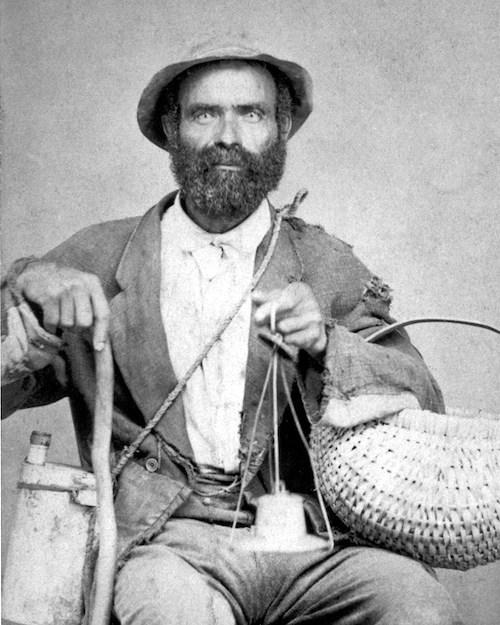

First-generation Mammoth Cave guide Mateson Bransford was one of the early enslaved explorers and guides/NPS

The two uncovered deep Bransford connections to the cave, and Lyons hatched an idea to honor those ties. Armed with the emerging revelations, she reached out to Jerry in 2004 to invite him to become a cave guide. When he said yes, he became the 5th generation of Bransfords to do so, and the first one to introduce visitors to the cave for more than six decades.

“It was almost as if they were never here,” said Jerry about the lost stories of his kinfolk. “I press on at age 70 because I won’t allow the story to go away as it did for 64 years. It is a blessing and a great opportunity to let people know what happened here.”

For 20 years, Jerry has carried the torch of his family’s underground history in the park and other African American stories almost lost to the depths. Some of the Bransford tale that Jerry and Lyons teased out of the archives and historical records is outlined below.

1st Generation

Mateson and Nicholas Bransford were not related by blood, but as enslaved men both carried the surname of their master. In Mat’s case, the master was also his father, but that did not affect his status since his mother was enslaved. The two men became guides in 1838, when their owner leased them to the cave manager. Many of the guides at the time were enslaved men who expertly led tourists through the labyrinthine underground passageways.

Cumulatively, the two guided for more than 100 years, even choosing to stay at the cave after they gained their freedom. Mat once explained it was because the cave was part of him and he was part of the cave. It was an unusual job at the time, as they escorted such celebrities as the Tsar of Russia, General Custer, and Ralph Waldo Emerson through the passageways.

“Slavery was a dark period in American history, but they had the run of life under the earth and were free,” said Jerry. “Visitors respected them and looked to them. They had a feeling of self-worth in the cave.”

2nd Generation

Henry Bransford was Mat’s son and Jerry’s great-grandfather. He and his wife, Alice, had six children, of whom at least two worked as guides. He died young, at 45 years old, and was laid to rest in the Bransford Cemetery on Flint Ridge with the simple inscription, "Henry Bransford, Guide." Henry’s and Alice’s headstones are the lone engraved markers of this cemetery.

Henry’s cousin, Will Bransford, was one of the most esteemed guides of his day. He served as the lead guide — supervising both Black and white guides — and was chosen as an ambassador for Mammoth Cave at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

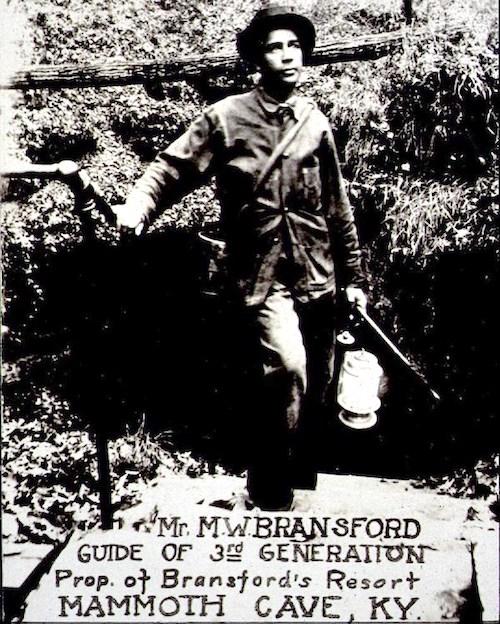

Third-generation Mammoth Cave guide Matt Bransford owned the Bransford Summer Resort for Black tourists/NPS

3rd Generation

Matt Bransford was the son of Henry and Alice and Jerry’s great-uncle. While the guides were racially integrated in his day, tourists still had to follow strict segregation laws. Along with working as a guide, Matt and his wife, Zemmie, operated the first lodging house for Black visitors. Called the Bransford Summer Resort, the two-story, 14-room hotel flourished during the early 1900s. It gave African Americans the same access to the wonders of the cave as whites had enjoyed for a century. The resort was eventually sold in 1934 for $3,000 — a price far under market value — to make way for the establishment of Mammoth Cave National Park. Matt retired from guiding tours in 1937.

4th Generation

In 1940, five 4th generation Bransfords were guiding: Clifton, Arthur, Eddie, Elzie, and George. They were a mix of brothers and cousins, one of whom was Jerry’s uncle. When the National Park Service officially assumed operations the following year, none of the Black guides were hired on. This ended the era of guides of different races working alongside each other and would have been the end of the Bransford legacy if not for Jerry.

“I feel a deep regret that they were turned away in 1941 after a hundred years of Black guides,” said Jerry. “My aunt was happy and proud that I came to work here and wear the uniform they were never able to wear.”

Honoring Them All

Jerry has been able to explore Flint Ridge during his tenure at the park. Once the site of old family homesteads and the Pleasant Union Baptist Church, the only remaining landmark is the Bransford cemetery. Saddened by its state of disrepair, Jerry vowed that before he retired, he would get it cleaned up as a place to commemorate his uncelebrated kinfolk.

In October 2022 his vision became a reality as 200 people gathered to dedicate the Bransford memorial obelisk. It names Mat and Nicholas and each of their descendants that worked as guides, honoring how they shined a light for countless visitors on the shadowed, underground world of Mammoth Cave.

“People of color had so much to do with the cave in the early days,” said Jerry. “The monument was a dream come true. I have worked hard to bring the story back and keep it alive, and the park has taken steps to acknowledge this history.”

Descendants celebrated the dedication of the Bransford family guide monument in October 2022/Edmonson News, Lynn Bledsoe