Weighed down by my camera gear and clearly not as fit as the pika crew farther up the trail, I stopped to catch my breath and wonder why I had agreed to go in search of plague in Lassen Volcanic National Park.

That's right, plague. The word normally conjures images of the Black Death of the mid-1300s, or maybe rats on a ship. You don't normally think of small, cute, furry mammals that can contract and spread the deadly disease in a national park. It would never have occurred to me that plague could be found within the confines of this national park in Northern California, but it is here.

That's why on a mid-October morning I had agreed to join Jonathan Bowser, a biological technician working as a contractor for the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Park Service, and his “pika crew” to learn about their research and field methods to study plague’s existence and effect in the park, with particular attention to its effect on pika.

Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for plague, is a “vector-borne disease” carried by fleas. While rare in humans, the National Park Service reports plague is “naturally occurring” among small mammals at both high and low elevations within Lassen. Plague’s deadly cascading effect impacts not only small mammal populations, but also the larger carnivores that eat the small mammals.

“There is lots of variation between species and individuals of species,” according to Bowser, so plague doesn’t have quite as much effect in foxes, wolves, or bears. Regarding people, Bowser said that “generally, humans are safe from plague even if they spend a lot of time outdoors. Keeping a respectful distance from wildlife is best for the sake of the animals as well as the human’s health, [and] it is just good practice. The most common ways plague spreads are from flea bites or handling dead carcasses. It [plague] cannot be spread from an animal bite … cases of plague in humans in the U.S. … are very rare [and] if caught early is easily treated with antibiotics…”

In other words, don’t let plague keep you from enjoying Lassen or any park unit. Just keep a safe distance from the wildlife, including those cute little critters looking for a tasty handout.

Regarding plague in the park, why study pika in particular? According to the NPS, American pika are a “charismatic indicator species” whose population numbers reflect various environmental conditions. In addition to being “interested in how active plague is in Lassen Park on a landscape level and what animals are affected by it, pika is one species of interest because their numbers have been declining and part of it is due to climate change, but there is something else causing pika numbers to decline, and we suspect it could be plague,” states Bowser.

Unloading the study gear, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Hitting the trail for a morning of field research, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

My morning in the field with the pika crew of Bowser, Hannah, Joe, Kat, and Megan began early – 6 a.m. In a couple of vehicles, we headed out toward the Bumpass Hell trailhead area. I remember standing on the trail at one point with my camera aimed in their direction, panting from the effort of trying to keep up with the crew as they hiked to their trap transects carrying not only their backpacks but also equipment for processing any small mammal they might catch in their live traps.

A Sherman trap setup, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Early mornings are for stuffing those traps with treats smaller mammals like pika (and chipmunks, squirrels, and deer mice) might find tempting: sweet oats, peanuts, apple bits, and molasses. For empirical purposes, I even smelled the container of goodies and got a whiff of stale peanuts (I’m pretty sure the wildlife is not as discerning as we humans regarding freshness).

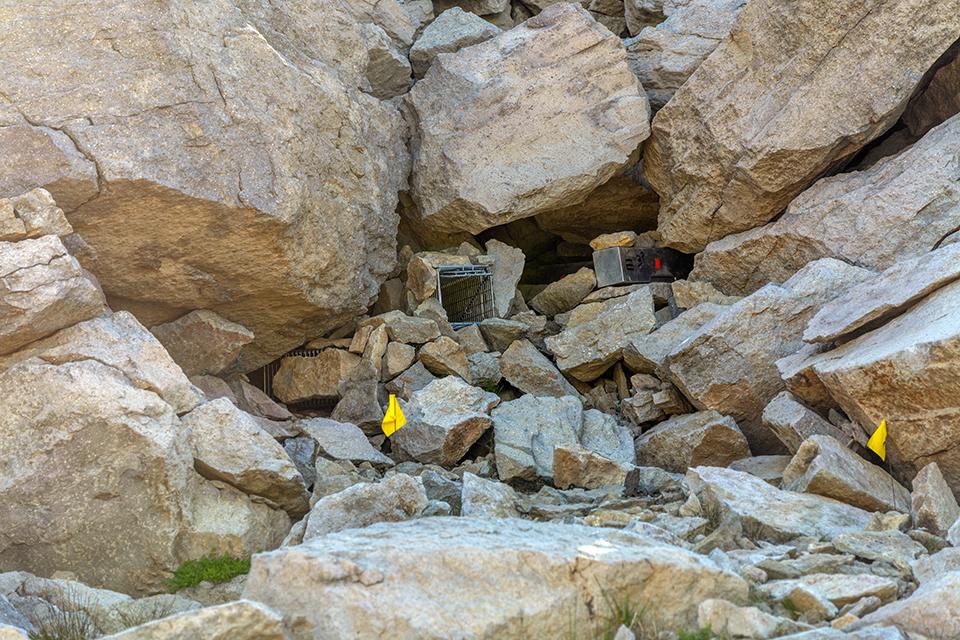

Along with cotton padding, handfuls of those goodies are thrown into either one of two trap types: Sherman (the smaller solid metal traps) or Tomahawk (the wire mesh traps that look more like cages). These traps are set in spots a small creature might frequent, sometimes camouflaged with talus rocks, and marked with little yellow flags. The traps are left open and enticing to whatever might come along (including much larger animals that can’t fit into those traps but do leave tooth mark and saliva calling cards).

During their July – October research season at Lassen, the pika crew set 6,000 traps in more than 15 different areas, both at high and low elevations.

Traps in the talus: a Tomahawk cage on the left, and a Sherman trap on the right, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Once the traps are filled with food, it’s time to wait a couple of hours, give or take, before the traps are checked. This wait time was a good opportunity for me to talk to everybody, not to mention enjoy the stunning park scenery bathed in golden light by the morning sun.

Lassen landscape, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Bowser told me the idea of studying pikas for plague started a couple of years ago with a pilot study. The Dixie Fire (2021) shut down the second season, making this year the first full season of field work. There’s funding for two more seasons, which is a good thing, since as much data as possible will enable park staff and scientists to understand “the dynamics of plague [in Lassen] and eventually contribute to a plague management plan for the National Park Service that will help manage outbreak of plague and species conservation related to plague.”

Although possessing varying backgrounds, Hannah, Joe, Kat, and Megan are united in their love of working outdoors and their strong interest in the plague aspect of the research they help Bowser conduct. They told me about themselves, and I told them about my work with the Traveler. Kat, a botany technologist also helping with another research project out in the park, took time to patiently answer my plant-related questions (for a future National Parks Quiz and Trivia piece, folks).

Upon completion of the wait time, traps were checked. While no pikas were captured on this day, several chipmunks and a golden-mantled ground squirrel awaited the processing station set away from the trail and out of sight of hikers. Why out of sight? Well, hikers are curious and would want to know what’s going on. The morning tasks the crew performs are time-sensitive, and while they will answer hikers' questions, it’s important they conduct their field efforts within a specific timeframe. That, plus they don’t want anybody coming along to grab-and-go with research equipment like the extra traps, extra marker flags, or even the table on which processing occurs.

Setting up the processing station, Lassen Volcanic National Park / Rebecca Latson

Again, all this processing is done within the space of a minute. The crew works quickly, efficiently, and carefully so as not to injure the animal. In the accompanying images, you’ll notice they hold the chipmunk gently but firmly, with fingers around the back of the neck (rather than the front, which would cut off air flow) while the rest of the hand supports the animal’s bottom end.

The animals were processed then released, data collected, and prior to noon, we all headed down the trail back to the parked vehicles. As Bowser drove us back to the Lassen's park headquarters, he stressed the importance of a good crew and how pleased he is with his own crew. These interns, paid a nominal daily stipend, give up a portion of their normal lives to live and work under sometimes less-than-optimal conditions. From my own observations, I could see how easily they got along with each other and how dedicated they were to the fieldwork. I know it takes a cohesive group of people to successfully conduct any sort of research, and I think this pika crew fits the bill.

With only a few days to spend in any park, I must usually pick and choose from my bucket list of things I want to do and places I want to go. Once I accomplish those goals, anything after that is a bonus. For me, that morning out in the field with the pika crew was the cherry on top of a great stay at Lassen, providing insight into some of the fascinating ongoing research within that national park.

Comments

Where might one find the analysis of the fleas?

A. Johnson, While I do not know for certain, it seems logical that flea analyses would be sent to Jonathan Bowser, since he is conducting the research.